NEW GLOUCESTER — Christian Becksvoort doesn’t want to be the ornery old guy who complains about how things are and wishes for the way they were.

He’s generally pretty well disposed, balanced and grateful, and at age 69, shows hardly a hint of slowing down. But he can’t help himself when it comes to talking about how it used to be, back in the day when kids were taught in school how to make things out of wood with their hands. They had to know how to measure, cut and hammer and were supposed to be endowed with enough functional woodworking skills to navigate the basics of home ownership and life.

“All those wood shops in high school have been turned into computer labs,” laments the fine-furniture maker from New Gloucester, better known as “the Shaker guy” because he handles the restoration work at Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in his town. “Every kid today is digitally fluid, but they can’t hang a bookshelf. I guess I’m a dinosaur.”

Dinosaur or not, Becksvoort has earned senior status among Maine furniture makers and, with it, the right to speak out. What we lose with generations of kids who can’t handle a saw or a sander are cultural connections to Maine’s past and people’s sense of independence and ability to take care of themselves, he said. In a state that may be home to more woodworkers per capita than any other, Becksvoort stands out for his absolute adherence to the Shaker tradition and the value of working within a personal aesthetic, as well as his commitment to making, and selling, high-end functional furniture that is designed and built to serve its purpose for a very a long time.

“I don’t do what I call California woodworking,” he says. “I don’t do it to impress the galleries. I try to keep it useful and simple and functional. That’s always first and foremost.”

He opened his studio in 1986 and has worked mostly alone since, designing, building and finishing custom furniture that is mostly inspired by the Shaker tradition, with unadorned lines. He works mostly with cherry and uses a simple oil finish. His client list has only about 200 names on it, but he’s known across continents – mostly North America and Europe – for his simplicity, purity and his exacting craftsmanship, executed with a personal stamp that distinguishes his work. He doesn’t care if you call him an artist or a craftsman and isn’t particularly concerned about the outcome of any such discussion.

“As long as they buy my furniture, they can call me whatever they want,” he said, his Yankee wisdom rising above the din of Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World” that’s playing on his workshop CD player. “If it has use, it’s craft. If it collects dust, it’s art.”

Master woodworker Chris Becksvoort poses for a portrait in his New Gloucester showroom. Becksvoort has a new book about his Shaker obsession.

A BOOK OF LIFE

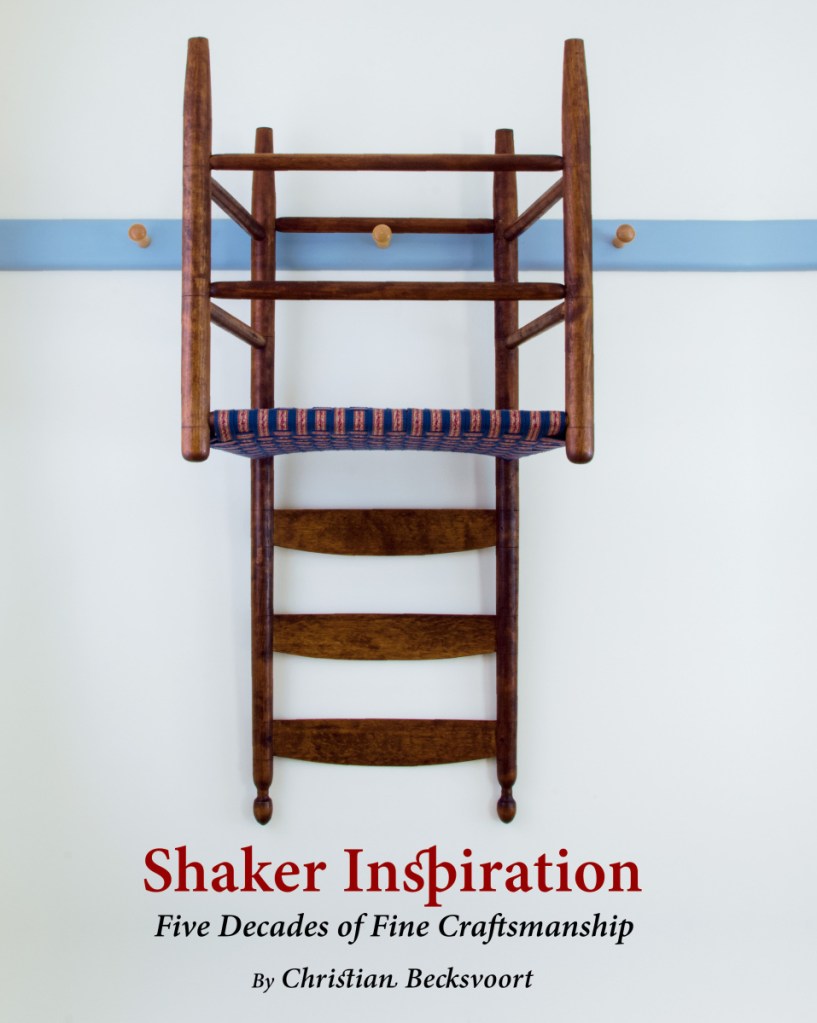

Becksvoort has written his third book about woodworking, “Shaker Inspiration: Five Decades of Fine Craftsmanship,” published by Lost Art Press late last year. The book is less how-to and more here’s-why – here’s why it’s important to know and respect your material, why design matters and why execution is as much an expression of aesthetic as a display of skills. Like the author himself, the book is folksy and philosophical, sensible and wry, and written with opinion and personality.

“What follows is just an overview of what has worked for me – a sharing of my experiences, failures and successes. Feel free to follow your own path. If any of my suggestions motivate or spark your own creativity, all the better,” he writes in the introduction.

He tries to find a balance in his shop between working by tool and by hand, and acknowledges that both approaches have merit. “I think that items spit out by CNC machines are useful for mass production, but have nothing to do with craftsmanship,” he writes, referencing computer-assisted production techniques. “I use hand tools where it shows, and machines where it doesn’t. You make your own choices.”

Becksvoort has become something of a woodworking celebrity, because of his friendships with writer Stephen King and actor Nick Offerman, a famously committed woodworker who offers a cheeky blurb for the book’s dust jacket. Becksvoort has enjoyed the glow of a cameo appearance on Offerman’s TV show, “Parks and Recreation.” He appeared as himself at a fictional woodworkers convention and was referred to by Offerman’s character, Ron Swanson, as the “modern master of the Shaker style.”

“It’s not bad having them as fans,” he says.

The new book reflects Becksvoort’s stature as someone whose opinion matters and is written with enough technical detail to satisfy serious woodworkers and with a breezy conversational tone to make for a fun and informative read for someone who simply appreciates a good story by someone qualified to tell one. His tone is confident and purposeful, and he writes with insight and experience, making a conversation about kitchen cabinets and the use of plywood versus solid wood interesting from a cultural perspective.

Master woodworker Chris Becksvoort”s New Gloucester showroom is full of Shaker-style furniture, the subject of his life’s work and a new book.

“I’m often asked if the Shakers would have used plywood had it been available,” he writes. “My standard answer is ‘yes and no.’ On the one hand, the Shakers were progressive and valued any time-saving device or material. I could picture their built-ins having plywood bottoms, partitions and shelves, but with solid wood faces, drawers and doors. On the other hand, ‘dressing … furniture of pine or white wood with the veneering of bay wood, mahogany or rosewood’ was considered outright deceptive and sinful … I rest my case.”

In addition to his three books, he’s written about 80 articles over 30-plus years for Fine Woodworking magazine. The books, he said, are more fun to write than the magazine articles, which are more how-to and “put into the editorial blender so all the articles read the same. It’s very vanilla, and that doesn’t bother me. But this writing is much more fun,” he says.

“With this, there was grammatical editing and punctuation, but no content editing. It’s my style and tone. This is about a philosophy, and it’s my philosophy. It’s 160 pages of my life.”

In the book, he shares measured drawings for 13 of his own designs and seven of his Shaker reproductions, as well as studio photos and drawings. The book reflects his education in forestry at the University of Maine and his understanding of wood movement, a career-long specialty that led to his development of an expansion washer, which accounts for the movement of wood, and an accompanying router bit used to drill the housing for the washer – both of which were exposed to trade violations while they were being manufactured in Taiwan for the Canadian company that Becksvoort approached with this design. “Before they even got into the catalog, a company in Taiwan was turning them out,” he says.

He includes charts and graphs to help woodworkers anticipate shrinking and swelling, down to the detail of how much a drawer front will move inside a house with forced-air heat. He also writes about the business aspect of being an in-demand furniture maker and acknowledges that after five decades, he’s still challenged to keep up with business side of things.

STILL IMPROVING

As he talked about his book, Becksvoort was finishing up the last of seven Shaker-inspired pieces that he was building for a customer in British Columbia, six straight out of his catalog with a few tweaks, another piece designed by the customer. The order included a five-door chest, a single-door cabinet, a breakfast table, a queen-size bed, a coat tree, a round stand and media cabinet. Based on the catalog prices of the six piece pieces and not including the custom media cabinet, the order was worth more $24,000.

Becksvoort embeds a silver dollar in each piece of custom furniture that he makes. It’s always hidden, secreted away in a place that’s never easy to find. It’s similar to boat builders, who place a penny under a new mast before setting it. Because this order was bound for Canada, Becksvoort hid Canadian-currency silver dollars with maple leafs in each piece.

By his count, he’s made about 850 pieces of furniture in 34 years, or about 24 a year. He aims to make 1,000 pieces before he retires.

“I have nothing against production furniture. Everybody needs a place to sit, sleep, stand and eat. Some people want something different, something really nice,” he says, pausing to turn down Neil Young, who is now singing, “Old Man.”

“My goal has always been to charge more and more and work less and less.”

He laughs – then catches himself.

“I am not trying to be funny or anything, or rip people off. Every piece, I try to improve a little bit. If I ever get to the point where I stop improving and start going down hill, then it’s time quit, because I don’t want my image tarnished.”

A Shaker round stand that he sells for $1,500 takes two days to make. A 15-drawer chest that sells for $12,750 requires 150 hours in the shop, or nearly a month of work.

That’s the kind of work he does, and the league he’s in.

Becksvoort came to Maine to study forestry at Orono and has lived in New Gloucester since 1978. His association with the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village shaped his sensibilities and his view of the world. Working with the Shaker community, he said, “was a real privilege, and it directly informed my work.” In addition to his own designs inspired by Shaker simplicity, Becksvoort repairs Shaker furniture and buildings on the village grounds. He also makes reproductions of traditional Shaker pieces and enjoys taking furniture apart to see how it was made. He’s always learning by understanding how other people have solved problems before him. “You can tell two or three people worked on a piece. Some dovetails are real crisp. Parts of others might be real sloppy,” he said. “You can learn a lot by taking it apart.” There’s a humility to Shaker simplicity that Becksvoort treats with reverence. For him, it always comes back to the opposite of what he calls “maximalism, or how much crap can we put on a piece of furniture?”

The idea of adorning a piece of furniture with a flourish that shows off the skills of the maker defeats the purpose of the piece, he said. “It just doesn’t go with my vocabulary of the Shaker ethic, where less is always better. A lot of woodworkers have dovetails (that are) a little bit proud and they have their joints stick out or they add little curly-cues. Dusting those things is a pain in the ass. Finishing is a pain. Why not have a smooth surface that is easy to care for? It’s not any less beautiful. But that’s strictly my opinion.”

And lately, his opinion seems to matter.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story