The photographer Mark Marchesi documents landscapes in transition. He spent four years traveling between Maine and Nova Scotia to take pictures of the Acadia that poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote about in his epic tale “Evangeline.” The cultural exodus that Longfellow described in his 1847 poem felt tangible to Marchesi when he began visiting Nova Scotia in 2012, prompting him to tell stories of displacement and loss over generations with photographs of empty landscapes dotted with abandoned communities and homes.

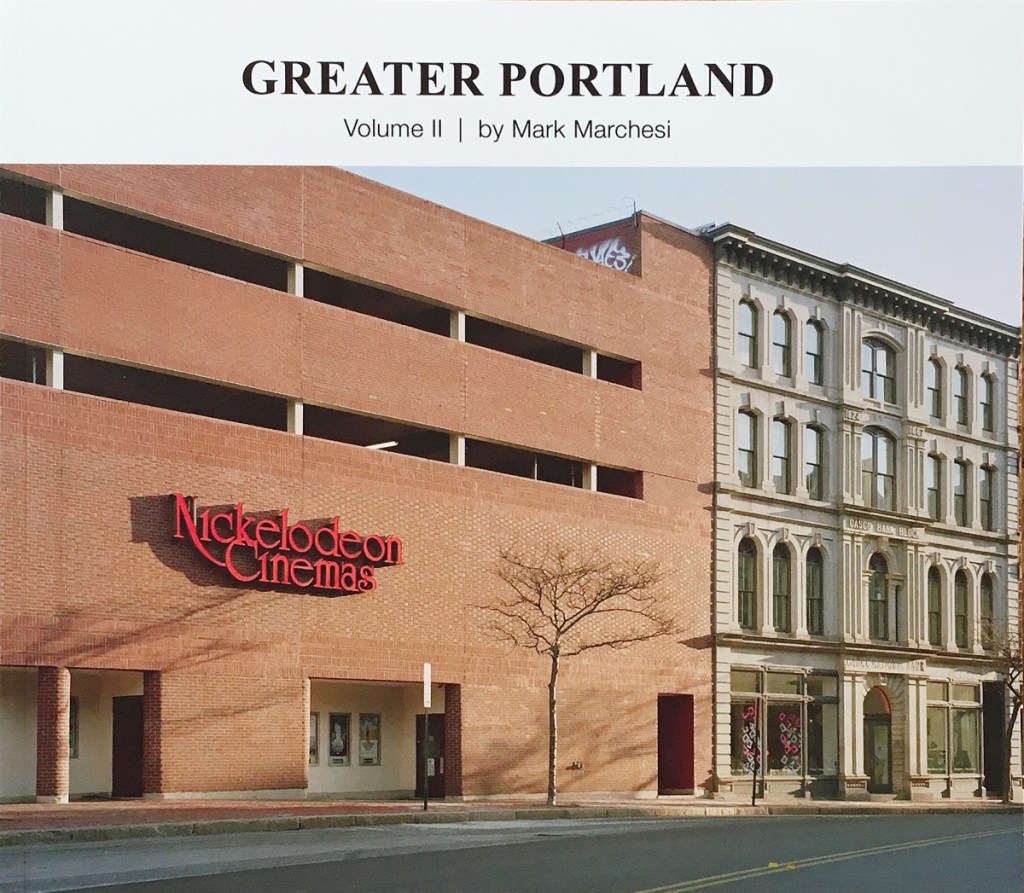

Marchesi’s latest photographic effort feels similar, if less dramatic. Marchesi, who lives in South Portland, has spent more than 20 years photographing in Portland, capturing the city’s most interesting and arresting landscapes in his ongoing “Greater Portland Project.” With his photos, he reveals the soul of the city, showing us the places – but never the people – that link Portlanders across generations with a shared sense of ownership and community. This month, he self-published his second book about the project, “Greater Portland, Volume II.”

More so than the first volume, this one shows how much Portland has changed in the four years since the first book.

Several subjects in the second volume – among them Joe’s Super Variety on Congress Street, Rufus Deering Lumber on Commercial Street and Century Tire on Marginal Way – were longtime landmarks, and all are now gone, either replaced by new development already or will be soon. His ongoing project dovetails with a larger discussion about Portland’s changing waterfront. Last week, the Portland City Council enacted a six-month moratorium on waterfront development to ease tensions between the fisherman who depend on the waterfront for their livelihood and the developers who want it for profit.

CITY IN TRANSITION

With his photographs, and without taking sides on the issue, Marchesi shows us what we’ve lost from the perspective of someone who is trained to observe and has been looking closely at Portland for more than two decades. He reminds us, for the sake of posterity and modesty, of the Portland of old that’s not so slowly being carved away by tall buildings and new construction.

His picture of Rufus Deering illustrates the city in transition. In the foreground, he places the lumber company’s large red metal shed, its garage doors closed, the parking lot neat and tidy. There’s a faded Rufus Deering Co. sign above the primary garage door, suggesting long-gone better days. As valuable as it was to have a lumber yard in the heart of the city, the land is more valuable for another use. Just behind the now closed lumber yard in Marchesi’s photo, we see a new building rising, its steel framework going up like an Erector set, portending the future for the lumber yard as well.

He represents Joe’s with a photo of the store before a rebuild, modest in comparison to the tall building that replaced it. The old Joe’s wasn’t much to look at, with a brick street-facing front, vinyl-sided upper floors and an ill-fitting sign running nearly the length of the building. The new Joe’s is still a convenience store, but much brighter and more upscale than the previous one. Marchesi calls it a “bleached version” of the original.

The site of the former Century Tire now supports the fast-casual chain Mexican restaurant Chipotle and a fitness center. Like the lumber yard and Joe’s, the loss of Century Tire represents not an architectural blow, but a deeper cut into Portland’s cultural fabric.

“The tire guys and Joe’s had a color that the new places don’t have,” Marchesi said. “They represent an attitude and a culture that is disappearing. So Century Tire wasn’t a pillar of architecture, but the community lost more in character than it gained in burrito bowls and spin classes.”

Marchesi, 41, has been taking photographs of Portland architecture on and off the peninsula since he arrived from Rye, New York, as an incoming freshman at Maine College of Art in 1995. He stayed around after graduating, putting down roots and raising a family.

In the introduction to his new book, he writes about what Portland was like back then. His first night in town, he and some new friends from MECA made their way down Congress Street, following the brick sidewalks into the Old Port while “weaving among the street musicians, bar hoppers, and gutter punks.” They peered into the windows of independent shops and browsed used discs at the CD Exchange.

“This was my new home, and the sense of belonging was immediate,” he writes in the introduction.

Twenty-three years later, Marchesi still feels that sense of belonging. Portland still has character, he said, but it’s losing it in small bits at a time. Portland today feels a lot more polished than 23 years ago, he said, more contemporary and much busier.

“It felt quieter 10 years ago. I remember being able to walk into most restaurants on a Friday or Saturday night and get a table right away. That’s rare now,” he said. “I hesitate to use the word cosmopolitan because we’re still a ways off, but that is the direction we’re heading. Compared to 1995 the difference is huge, but it’s definitely accelerated in the last 10 years.”

SOUL SEARCHING

Marchesi is interested in finding the soul of the city with his photos. He learned about the idea of the soul of a photograph from the Canadian-American architectural photographer Robert Polidori, who has taken photos in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, in Beirut after the bombs and in Chernobyl after the meltdown. Polidori was one of the artists Marchesi printed for when he lived in New York City in 2003-04. “He would usually come in to view proofs at the end of the day, and then we’d go out after. Robert’s a character,” Marchesi said. “Some of his views can be pretty outlandish, but I learned a lot from seeing his process and talking about photography over drinks.”

Polidori often made images without people in them, instead suggesting the presence of humans by the active nature of his photographs. Marchesi accomplishes much the same thing. Only a handful of photographs in the new book include human beings. Instead of a human presence, these photos have a deeper, more elusive quality than something physical, and also more powerful.

Marchesi calls that quality “the true character” of Portland, or the soul of the city. When he began posting images from his Portland project to social media many years ago, he observed that people weren’t just responding to his photos. They saw images of themselves reflected in the photos, he said.

“I shoot a lot in the early mornings, when there aren’t many people around anyway. And when I’m out during busier times, I intentionally wait for people to vacate the frame,” he said. “I don’t want the images to look too lifestyle or editorial. I think of my pictures as building portraits – the buildings have plenty of personality, and I don’t want people taking away from that.”

The book includes interior portraits from the dusty former Portland Company buildings, the stately Masonic Temple and Mahoney Middle School in South Portland, including a very pink home economics room.

OLD-SCHOOL/NEW SCHOOL

Marchesi shoots almost exclusively with a Linhof 4-by-5 large-format film camera. He also uses an iPhone. “I’m constantly scouting good vantage points, and when I see a good shot, most of the time I have to wait to shoot it,” he said. “Sometimes I take an iPhone pic to remember, sometimes I write it down. I’ll think about when the light will be best, then keep going back until it looks the way I envisioned it. A lot of times I need to wait until I can catch a scene without cars too. Some shots take me a long time to capture correctly on film. Years even. Some of the interiors are taken with higher-end digital cameras, because interiors can be especially challenging with film, and when I get access to someplace like the Masonic Temple, I want to be 100 percent sure I get the shots.”

He’s divided the book into at least three distinct bodies of work. One is the changing landscape of Portland, which is an encompassing theme that unifies much of his work. Another section is dedicated to his iPhone images, which he stacks in rows of three, with nine to a page. Collectively, they offer an engrossing look at the range of Portland architecture, residential and commercial.

Another dominant theme is the winter of 2015, which brought record snow totals to Portland. Marchesi spent a lot of time that winter on the streets, documenting. One morning, he walked across the Casco Bay Bridge in sub-zero temperatures to get a photo of the harbor filled with ice “because I might never see it again. And the icicles throughout town were unreal – the size of tree trunks, extending from the third story of a houses to the ground in some cases,” he said.

When the snow piles up, the city streets begin looking like miniature dioramas, he said.

“That’s when Portland feels most authentic too,” he said. “The tourists are gone, and there’s no room for frivolity. Those extreme bouts of cold and snow deflate any ego we all grew during the warmer months. It’s sobering.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story