To me at least, one of the funniest commercial slogans is the “ARS GRATIA ARTIS” banner that circles the head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s Leo the Lion, who we see roaring before so many movies.

The phrase is a Latin version of “art for the sake of art,” an early-19th-century French slogan (“l’art pour l’art”) that came to imply that “true” art was autotelic – pure in itself and free from any ideological or utilitarian purpose.

This has come to be a troubled but highly active American art myth; many artsy Americans believe this. But, quite simply, “art for art’s sake” is a reactionary idea: To intentionally exile all moral, social, societal or humanist concerns from culture is to stand firm for the societal status quo. And in a capitalist society, that generally means the folks with the most money. And Leo the Lyin’ ain’t fooling anyone: The purpose of MGM’s pictures has been to generate profit.

In 2004, Sony bought MGM for $5 billion. Profit is purpose.

Now on view at Able Baker Contemporary is the brilliant “Print, Protest, Power,” curated by Bates College professor Myron M. Beasley. This is the more obvious side of culture with purpose. The exhibition features a mix of local and nationally acclaimed artists with an eye to prints and posters. “Propaganda” is a term we often use to dismiss the art featuring messaging with which we don’t agree. But without it, the United States probably wouldn’t exist. I contend, for example, that Paul Revere’s exaggerated engraved image of the Boston Massacre is the most important work of art in American political history. It helped foment our revolution, after all. Art is culture and human culture is alive and ever-changing.

Beasley’s artists straightforwardly state their purpose. Their works generally focus on identity politics and seek to instill active and dynamic discourse – the words and terms of how we talk about culture. Emory Douglas, for example, is the former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party. He is also a great artist, an excellent designer and a maker of beautiful prints. “Beauty” might seem an out-of-place term here, but it isn’t, if you think beauty can be the intelligent blending of aesthetics and purpose. And great design is certainly beautiful to me.

The warm and charming Douglas attended the opening and conducted workshops and conversations with the public when visiting from California. A 1969 psychedelic-styled poster, for example, features a Black woman holding a spear with a rifle slung over her back and the phrase: “Afro-American solidarity with the oppressed People of the world.” It might be a threatening object to some folks, but it echoes another of the greatest works of the American Revolution, Ben Franklin’s chopped up snake with the phrase, “Join or Die.”

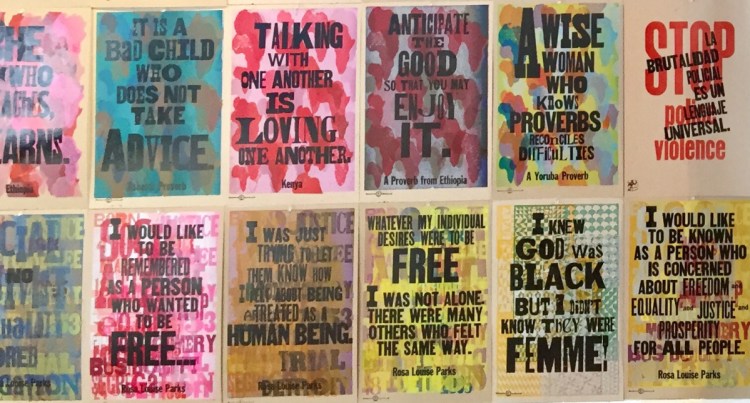

The letterpress prints of Alabama artist Amos Kennedy Jr. cover an entire wall. It is one of the most powerful visual installations of art seen in Portland in a long time. (Its only competition, not ironically, is Daniel Minter’s installation in the Portland Museum of Art’s Biennial, which comes down Sunday. Minter’s work is largely about his personal and spiritual experience as an African-American artist.)

Kennedy’s works are colorful posters with activist phrases and often quotes by notable civil rights leaders and artists, from Cicero (“If you have a garden and a library you will want for nothing”) to Rosa Parks (“I would like to be remembered as a person who wanted to be free”). The effect of the rhythmic density of Kennedy’s 200 or so gridded prints covering the giant wall is to convey a cultural discourse: Terms like “queer,” “gay,” “freedom,” “loving” and “people” flicker with something like an electric charge as your eye finds them again and again in various phrases. And this feeds the poetic qualities of the texts. To unpack “I knew god was black but I didn’t know they were trans!” would take me pages: assumptions about faith, religion, race and the ever-progressive dynamism of the terms we used to talk about gender. “They” is now the proper non-gendered singular we use to talk about people. Our language evolves and artists very much are part of how that happens in a society, in a culture.

Alisha Wormsley

A particularly striking work is Alisha Wormsley’s print featuring the stenciled words: “There are black people in the future.” And this stands as a reminder that culture isn’t just about where we live, but where we are going.

To wit, Maine College of Art professors Elizabeth Jabar and Colleen Kinsella show together as the Future Mothers collective. This nod to the future says a great deal about their implied audience; instead of the assumed “white-male gaze,” they’re talking to young women, and this jump-starts the revolutionary aspects of the discourse of their work. Jabar has long followed identity politics as the path of her art, even years ago working in terms of Syrian culture. At the moment we think of Syria as a bordered political entity, but it was long a far broader cultural term for people of the Middle East, a cultural term that went far past borders, religions and sects. One Future Mothers work, for example, includes a red cross on raw linen and the words “resist, be right, grow, wake up, maternal ethics, equal rights and justice, water, thanks.”

Emory Douglas

H.R. Buechler’s prints on the wall didn’t strike me as particularly engaging until I watched the five-minute video presentation of “D2: Towards a New Ideology of (Print) Production” with the text articulated by a computer reader voice. The project is a powerful manifesto, specifically geared toward print artists, that addresses production, intention and the pratfalls of commercial culture.

Beasley’s installation exudes inclusive energy. It reaches out to the viewer visually, ethically, morally and politically. The works make a compelling case not only that there is much to be done, but that such efforts can and will be successful. The art builds on successes of the past as well as current topics of change politics, so when it looks to the future, it does so not desperately, but confidently. Viewers are challenged to compare their own ethics with their morals, and they are invited to join a movement for justice. What makes this different from other regional exhibitions focused on identity politics (such as curator Nat May’s largely excellent biennial at the PMA) is the specific intent of the works to persuade a possibly-not-yet-persuaded audience. The poster approach, in particular, reaches out into social space. It seeks to address everyone, and not just a museum or gallery audience. It is welcoming rather than shrill. It is positive, optimistic and constructive. This is even apparent with the accessibility of the works: Able Baker is free and open to the public. The Future Mothers collective offers work for free to the public, copies of Buechler’s manifesto are free, and Kennedy’s often-exquisite prints are just $25 each.

“Print, Protest, Power” is a brilliant, exciting, accessible and visually stunning show. And it is a powerful model for things to come.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

_____________________________

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 3:42 p.m. on June 4, 2018, to correct the hours of operation of the Able Baker Contemporary.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story