From the founding of the United States until long after the Civil War, hundreds of the elected leaders writing the nation’s laws were current or former slaveowners.

More than 1,700 people who served in the U.S. Congress in the 18th, 19th and even 20th centuries owned human beings at some point in their lives, according to a Washington Post investigation of censuses and other historical records.

The country is still grappling with the legacy of their embrace of slavery. The link between race and political power in early America echoes in complicated ways, from the racial inequities that persist to this day to the polarizing fights over voting rights and the way history is taught in schools.

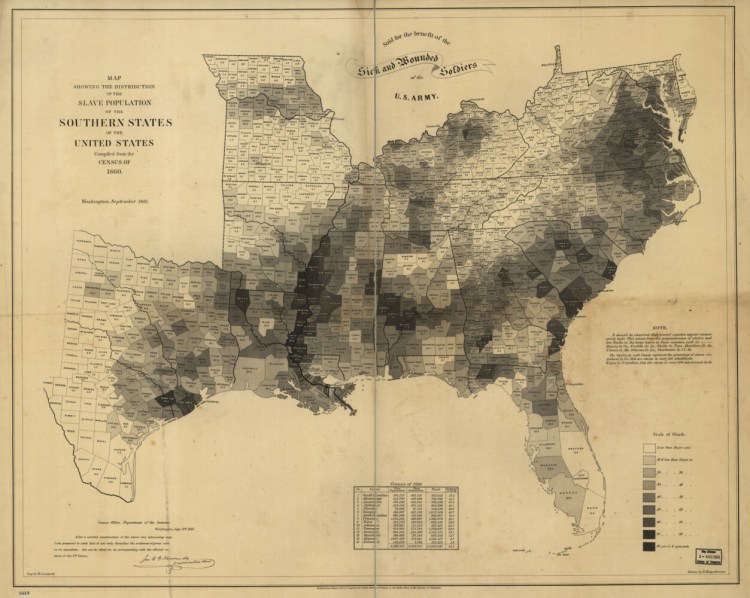

The Washington Post created a database that shows enslavers in Congress represented 37 states, including not just the South but every state in New England, much of the Midwest, and many Western states.

Some were owners of enormous plantations, like Sen. Edward Lloyd V of Maryland, who enslaved 468 people in 1832 on the same estate where abolitionist Frederick Douglass was enslaved as a child. Many exerted great influence on the issue of slavery, like Sen. Elias Kent Kane, who enslaved five people in Illinois in 1820, and tried to formally legalize slavery in the state.

William Richardson, for example, a Democrat who fought for the Confederacy, died in office in 1914 after representing Alabama for 14 years. Another Democrat, Rebecca Latimer Felton, a suffragist and a white supremacist, was appointed to fill a Senate vacancy in 1922 and briefly represented Georgia at age 87. The first woman ever to serve in the Senate was a former slaveholder.

Enslavers came from all parts of the political spectrum. The Post’s database includes lawmakers who were members of more than 60 political parties. Federalists, Whigs, Unionists, Populists, Progressives, Prohibitionists and dozens more: All those parties included slaveholders.

The most common political affiliation among enslavers was the Democratic Party – 606 Democrats in Congress were slaveholders.

While the early Republican Party is associated with abolition, The Post found 481

This database helps provide a clearer understanding of the ways in which slaveholding influenced early America, as congressmen’s own interests as enslavers shaped their decisions on the laws that they crafted.

One example: When Congress voted on the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which prohibited the expansion of slavery in the northern half of the country, the House and Senate contained a nearly equal number of slaveholders and non-slaveholders, a Post analysis found. Almost twice as many slaveholders, 44 percent, voted against the agreement, compared with 25 percent of non-slaveholders. The law was crafted by a slaveholder, Henry Clay, who is so renowned as one of America’s greatest statesmen that 16 counties across the country are named for him.

When Congress voted during the Civil War on the 13th Amendment, which added a ban on slavery to the U.S. Constitution, nine men who had been slaveholders remained in the Senate. Just three of them voted to approve the amendment, while 35 out of 40 non-slaveholders voted yes.

Historian Loren Schweninger, who spent years driving to more than 200 courthouses across the South to collect records on slavery, notes the importance of lawmakers’ personal stake in slavery as they passed laws codifying the practice. “They were protective of the institution, that’s for sure,” Schweninger said of state and federal lawmakers’ relationship with slavery. “There was brutality and there was all kinds of exploitation of slaves – but still there were laws.”

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., said he thinks about that history in the halls of Congress, from the portraits on the walls to the votes once taken there.

“I’m very conscious of this as only the fourth Black person popularly elected to the United States Senate. . . . The very monuments you walk past: There’s very little acknowledgment of the degree that slavery, that wretched institution, shaped the Capitol,” Booker said in an interview. He added, “All around you, the very Capitol itself, was shaped by this legacy that we don’t fully know or don’t fully acknowledge.”

The same is true of the White House. Of the first 18 U.S. presidents, 12 were enslavers, including eight during their presidencies.

To Booker, those stories about his predecessors in Congress call for action from their counterparts today – namely, a bill he has championed that would commission the first national study on reparations for the descendants of enslaved people.

Without acknowledging the harm and trauma caused by slavery, both for the enslaved and their descendants, “it’s very hard to heal and move on,” Booker said. “We have never really tried, in any grand way as a country, to take full responsibility for the evil institution of slavery and what it has done.”

America’s atrocity was carried out not in shadow, but with extensive documentation, in carefully recorded censuses and court cases and wills. To create this database, The Washington Post researched all of the 5,558 men and one woman, Felton, who served in the U.S. Congress and were born before 1840, meaning they came of age before the Civil War. The verdicts on who enslaved people and who did not are based on journal articles, books, newspapers and many other texts, with the vast majority of the information coming from the 1790 through 1860 decennial censuses.

Today, as America struggles with how to understand its history and which historical figures to honor, many of these lawmakers’ statues stand in town squares across the country, and their names adorn streets and public schools, with almost no public acknowledgment that they were enslavers.

The men, women and children they enslaved are less recognized still, often recorded in a census by just their age and gender, without even a name.

The nation’s capital, like many cities, is dotted with reminders of these members of Congress. Rep. John Peter Van Ness of New York, an enslaver, has a D.C. elementary school, a street and a Metro station named in his honor. Sen. Francis Preston Blair Jr. of Missouri, who has a statue in the Capitol and a homeless shelter named after him in Northeast Washington, was an enslaver who opposed allowing Black citizens to vote after the Civil War. (The guesthouse across from the White House is named for the senator’s father, who was not a lawmaker but also was a slaveowner.)

Cities, towns, universities and other institutions across the country have started commissions to reconsider whose names should be on buildings and streets, and many institutions have removed statues and portraits because the people they honored enslaved others. But until now, there has never been a comprehensive list of slaveholding members of Congress.

This database helps reveal the glaring holes in many of the stories that Americans tell about the country’s history.

The opening page of Rep. Charles Miner’s 1916 biography says, “He made the first persistent, long-continued effort on the floor of the House looking toward the final extinction of slavery.” His Wikipedia page begins by introducing him as “an anti-slavery advocate.” Nowhere on that page or in the biography’s lengthy discussion of Miner’s repeated efforts as a congressman in the 1820s to outlaw slavery in the District of Columbia does it mention that Miner himself enslaved eight people, according to the 1810 Census, when he was a 30-year-old newspaper publisher in Pennsylvania.

Rep. John Floyd, who ran for president in 1832, is described in historical accounts as an opponent of slavery who went so far as to raise the possibility of turning Virginia into a free state while he was its governor. Left unmentioned: Floyd, too, was a slaveholder. The 1810 Census shows he kept four people in bondage in Christiansburg, Va.

History remembers Rep. John McLean, an Ohio congressman and then a longtime Supreme Court justice, as one of two jurists who dissented in the notorious 1857 Dred Scott decision, in which the Supreme Court ruled that Black Americans were not citizens under the Constitution. Yet McLean was also one of the rare residents of free state Ohio who was recorded as a slaveowner in the 1820 Census, when he was serving on the state’s Supreme Court.

Determining who was an enslaver can be complicated. As recent revelations about Founding Father Alexander Hamilton and hospital and university namesake Johns Hopkins make clear, making a judgment about whether someone was a slaveholder based on the handwritten records of the 18th and 19th centuries is painstaking and imprecise work.

The Post concluded that 1,715 members of Congress were enslavers at some point in their adult lives, including at least one lawmaker who held Native Americans in bondage. Evidence suggests that another 3,166 congressmen did not enslave anyone. The Post could not find enough evidence to reach a conclusion about 677 congressmen. As more information comes to light, The Post will update the database.

Determining whether a lawmaker enslaved others does not reveal everything about his role in maintaining or questioning the institution of slavery. Some members of Congress who once enslaved people later freed them. Or take, for example, Sen. John A. Logan, whose statue sits on horseback in Washington’s Logan Circle for his exploits leading Union troops during the Civil War.

An Illinois senator and defender of the Union who was not a slaveowner, Logan worked as a state lawmaker to ban Black people from the state of Illinois and voted in Congress for the divisive Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made the federal government responsible for finding and returning those trying to escape bondage, even if they were caught in free states. But after the Civil War, the Democrat turned Republican changed direction, advocating as a senator for Black Americans’ civil rights.

The institution of slavery in America predated the first Congress by 170 years and was deeply rooted among the wealthy families most likely to send someone to Washington.

Multiple members of Congress were among the last slaveholding Northerners.

In Delaware, residents elected two senators, Willard Saulsbury Sr. and George Read Riddle, who were both among the dwindling number of enslavers in the state in 1860. Riddle was one of just two slaveholders left in his county that year. Both of Delaware’s senators went on to vote against the 13th Amendment ending slavery.

Locally, 85 percent of the men Maryland and Virginia sent to Congress between 1789 and 1859 were slaveholders.

Rep. John T.H. Worthington was listed as the enslaver of 29 people in the 1840 Census while he was representing the Baltimore area in the House. He sold his own enslaved daughter for $1,800 to a man who wanted her to bear more enslaved children, according to an account written by James Watkins, who managed to escape slavery.

Worthington’s daughter, whose name is not recorded but whose pious faith Watkins remembered, refused to consent to sex with her new enslaver. As punishment, she was beaten to death. Watkins writes that he sat beside her as she died: “She left behind her a bright testimony that she was going to that Saviour from whom it is impossible for all the American laws, and opinions, and prejudices combined, to keep back the soul.”

Many members of Congress played a role in such harrowing stories. Toni Morrison’s novel “Beloved,” a cultural flash point in Virginia’s election this fall, is based on the true story of Margaret Garner, who made the wrenching decision to kill her toddler rather than allow her to grow up in chains. One of Garner’s enslavers was Rep. John P. Gaines, a Whig who represented Kentucky in Congress from 1847 to 1849.

Knowing which members of Congress were enslavers could lead to changes in how American history is told.

Sen. Rufus King, a signer of the Constitution and an 1816 presidential nominee, gets a section of his Wikipedia page devoted to his anti-slavery activism. Yet it is nearly impossible for a curious student – or perhaps someone who walks past the New York City plaque honoring him – to search the Internet and find that in 1810, King also owned a human being.

Or take the case of Celia, a 19-year-old enslaved woman who killed the septuagenarian man who owned her after five years of sexual abuse. She went to trial in Missouri in 1855 claiming self-defense. Judge William Augustus Hall instructed the jury that Missouri’s laws protecting women who resist sexual assault did not apply to Celia. Six years later, he was elected to Congress.

An acclaimed book on the case says that “Hall’s views about slavery are unknown.” It changes the story to note that in the 1850 Census, Hall reported enslaving four people, including a woman not much older than Celia.

For Crystal Feimster, a Black historian at Yale University, a full accounting of these stories from American history is essential to understanding America today.

“There is a way in which people want to disconnect and say, ‘I didn’t own slaves. My family didn’t own slaves. So let’s keep moving,’ ” she said. “We have to tell them why it’s important and why it matters and what it tells about where we are in this present moment.”

She pointed to voting rights, the vast racial wealth gap and the disproportionate impact of violence on people of color as examples of current-day struggles that spring directly from the history of slavery. “What’s happening politically has deep roots in our political leaders’ investment in slavery and how they wielded that power for their own personal benefit,” she said. “People who don’t know that longer history can’t draw those connections.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story