Spectrum is coming under fire for moving local-access channels to what one opponent is calling “digital Siberia.”

The cable company’s decision to put Maine local programming on channels in the 1300-range reflects a national strategy intended to squeeze local programming out of the lineup, says the head of a public-access advocacy group.

Cable companies are required to provide local-access programming in the contracts they sign with municipalities so viewers can watch such events as town meetings, local celebrations and public hearings before government boards. Some critics call Spectrum’s relocation of community channels an abuse of power, said Mike Wassenaar, president and CEO of the Alliance for Community Media, based in Minneapolis.

“If you starve the service, you can shed yourself of the service. Many people think it’s unfair and an abuse of power,” Wassenaar said.

A bill being drafted in Augusta would restore local-access programming to lower channels.

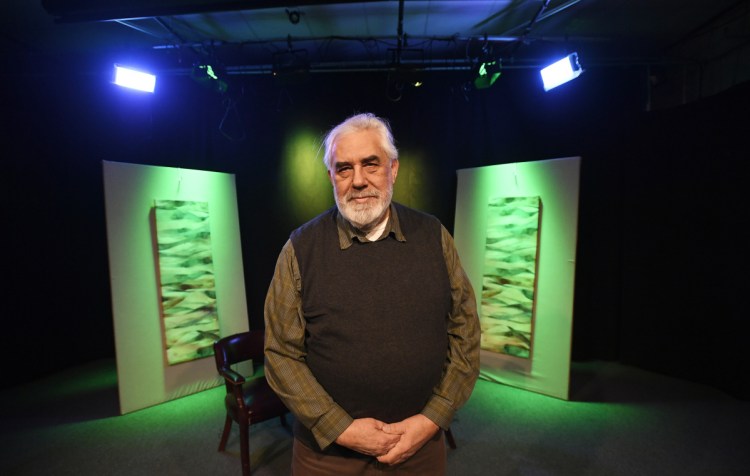

Tony Vigue, who ran South Portland’s local-access channel for 21 years and is now a cable contract consultant, said Spectrum, the state’s largest cable system, moved community programming stations from their historic, single-digit channel numbers to channels 1300 and above after it completed a conversion to all-digital transmission last fall.

“When you move the channels to one of those higher numbers and have very little notice … fewer people watch it and when it comes time to negotiate a renewal (contract between the town and cable system) there won’t be a big hue and cry in the community for these channels,” said Vigue, who uses the phrase “digital Siberia” to describe the channels’ new locations.

Vigue and others also allege that Spectrum is broadcasting a degraded signal quality of the town meetings and locally produced shows that are typically seen on the public-access channels.

If cable companies can eliminate the local-access channels, he said, they will no longer have to supply video equipment to the stations and may be able to cut franchise fees, part of which pay camera operators and others at the local stations.

Tom Handel works in the control room at Community Television Network in Portland last year. Most municipal agreements give cable companies access to their communities in exchange for a franchise fee and a dedicated, local cable channel and broadcast equipment. Staff photo by Brianna Soukup

A spokesman for the cable company declined to address Vigue’s allegations, but said customers still have access to all channels in their programming packages. Andrew Russell, director of communications in the Northeast for Charter Communications, which owns Spectrum, said grouping and relocating local channels to the 1300s “reflects how people find and watch content today.”

“Customers tell us they like grouping the channels by theme because it makes it easier to find their favorite programming,” he said.

Most of Maine’s cable access channels are now sandwiched between Public Broadcasting’s Create channel of cooking and home improvement shows and a subscription-based Chinese language channel.

Robert Nichols, whose nonprofit Maine Coast TV provides programming for 14 community-access channels in the midcoast, doesn’t accept Spectrum’s explanation. Like Vigue, he believes relocating the channels is an attempt to drive down viewership and ultimately relieve Spectrum of its local programming obligations.

The programs in his area aired on low channel numbers amid the channels for local network affiliates. Viewers would often come across the local programming while channel surfing between those affiliates, he said, but they can’t do that with the new channel numbers.

“You’d have to push the button 1,300 times,” he said.

He said his organization has begun to stream shows on its website, mainecoast.tv, so people have a reliable place to see local programming and as a hedge in case the communities lose their slots on cable.

POWER PLAYS

The decision to move the channels is not unique to Spectrum, but the company seems to follow the practice more than other cable operators, Wassenaar said.

“It seems to be Charter’s practice,” Wassenaar said of Spectrum’s parent.

In Hawaii, the company tried to move the community-access channels, but backed down after state officials and legislators complained and threatened legislation. Wassenaar said, however, that Hawaii has stronger state regulation of cable companies than Maine, where oversight lies almost exclusively with local officials.

Even so, concerns about Spectrum’s moves are gaining attention in Augusta. A bill being drafted would force Spectrum to move the programming back to lower channel numbers, nearer the channels for network affiliates.

The bill has been proposed by Sen. David Woodsome, R-Waterboro, who said that the balance of power between local communities and the cable company has gotten out of whack.

Woodsome said he believes strongly in capitalism, but cable companies “want the whole hog” when it comes to earning money from customers in the towns they serve and are not offering much in return.

“They’re really not working cooperatively with the towns anymore,” he said. “We need to have a good conversation about what direction we’re headed in.”

Russell, the spokesman for Charter Communications, declined to comment on the legislation because a final draft of the bill hasn’t been completed.

LOCAL CONNECTIONS

Local-access programming grew out of the original contracts drawn up between municipalities and cable startups in the late 1970s and ’80s. Towns and cities had leverage then because, under federal law, cable companies had to negotiate contracts with local governments for access to their residents.

But town officials also were pressed by residents, who urged them to reach a deal so they could have better reception and a wider array of programming choices offered by nascent cable companies.

Most municipal agreements give cable companies access to their communities in exchange for a franchise fee and a dedicated, local cable channel and equipment to produce local broadcasts. Generally, community TV broadcasts local council and board meetings on television, along with other local events and, often, shows about local history or profiles of interesting residents.

Nichols said his programming includes local parades, festivals and weekly shows at the local animal shelters showing dogs, cats and other animals available for adoption.

The franchise fees cable companies pay to municipalities can be significant.

For instance, South Portland gets a franchise fee of 5 percent of Spectrum’s revenue that comes from services supplied to residents, said Moe Amaral, station manager for South Portland Community Television.

Of that, the community station gets about 70 percent, which amounts to about $350,000 a year, Amaral said. That pays for the operations of the station, he said, and to buy equipment.

Amaral said the deal is typical of what Spectrum has with most communities it serves in Maine. South Portland signed a 15-year contract with Spectrum in 2016, he said.

Cable companies, which often bundle other services such as internet access, are outliers among others that provide what is increasingly considered a necessary service. Phone, water and electric companies don’t deal with local officials because they are regulated by the state Public Utilities Commission. Over-the-air broadcast stations are overseen by the Federal Communications Commission.

But cable companies remain largely unregulated, constrained mainly by free-market competition and the long-term contracts they sign with individual municipalities.

Vigue said as the cable companies have grown larger, they recognize the value of the lower-numbered channels occupied by community stations. He suspects that the low-numbered channels previously occupied by community stations will eventually be sold to cable shopping networks.

Woodsome said a draft of his proposed legislation will probably be ready in a couple of weeks. He said a public hearing before the Energy, Utilities and Technology Committee will likely be scheduled for March or April.

In addition to moving the channels back to their traditional location, the bill also would require that cable companies provide service to areas with a density of at least 15 homes per mile. Vigue said towns and cities used to negotiate for that standard in their contracts, but the cable companies now rarely agree to anything less than double that density.

He also said that towns and cities are banding together to push for some of the things they want. There are about 70 public, educational and government stations in Maine and they have joined together to form the Community Television Association of Maine, which is affiliated with the Maine Municipal Association.

The MMA is supportive of Woodsome’s bill, said Garrett Corbin, a legislative advocate with the organization.

Corbin said it’s “disheartening” to see Spectrum being unresponsive to local concerns such as the channel locations, but also other matters, including serving residents in less-dense rural parts of the state.

Edward D. Murphy can be contacted at 791-6465 or at:

emurphy@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story