For the first time, all 238 paintings in Maine artist Robert Shetterly’s “Americans Who Tell the Truth” portrait series are on view together at Syracuse University in New York. Shetterly, who lives in Brooksville, began painting portraits of courageous Americans 17 years ago as an act of defiance against the war in Iraq.

He’s painted portraits of whistle-blowers, crusaders, activists and truth-seekers, some famous, some unknown, all rendered with empathy and accompanied by quotations from the subjects, incorporated as part of the painting. “Instead of ranting any more about people in our government and the Bush administration who were lying about our reasons for being in Iraq, I surrounded myself with Americans I admired. I changed the energy around me and what I could do as an artist and a person,” he said.

Until last week, Shetterly had never seen the portraits all together. Nobody had, because they had never been hung together. Prior to the show at Syracuse, the largest exhibition involved about 60 portraits from the series.

Shetterly attended the opening Nov. 29 and participated in a campus discussion with some of the subjects. They’re on view at Schine Student Center through Friday.

Experiencing the portraits en masse, he said, was like attending a vocal performance of friends. “The sound of their chorus was deafening,” he wrote of the experience. “I expected a sensation I could describe in words. I had expected, glibly, to be overwhelmed, but not confused, disoriented, unable to respond, unable to recognize what presence I was in. I was not expecting the roar of their silent voices, an accumulated goodness far greater than my own – in fact, incompatible with me.”

Over the years, working alone in his quiet studio, he always felt he was a medium for each portrait, a way for the subject to speak. “But what I had not realized is that they have been building for 17 years a collective voice that could never have been predicted until they were permitted to congregate in the same place at the same time,” he wrote.

He thinks of these paintings stacked in his basement all these years, small groups of them – tribes, hunting parties – making forays to schools, libraries and churches in quartets and octets, “not yet knowing they had been hired to form a symphony.”

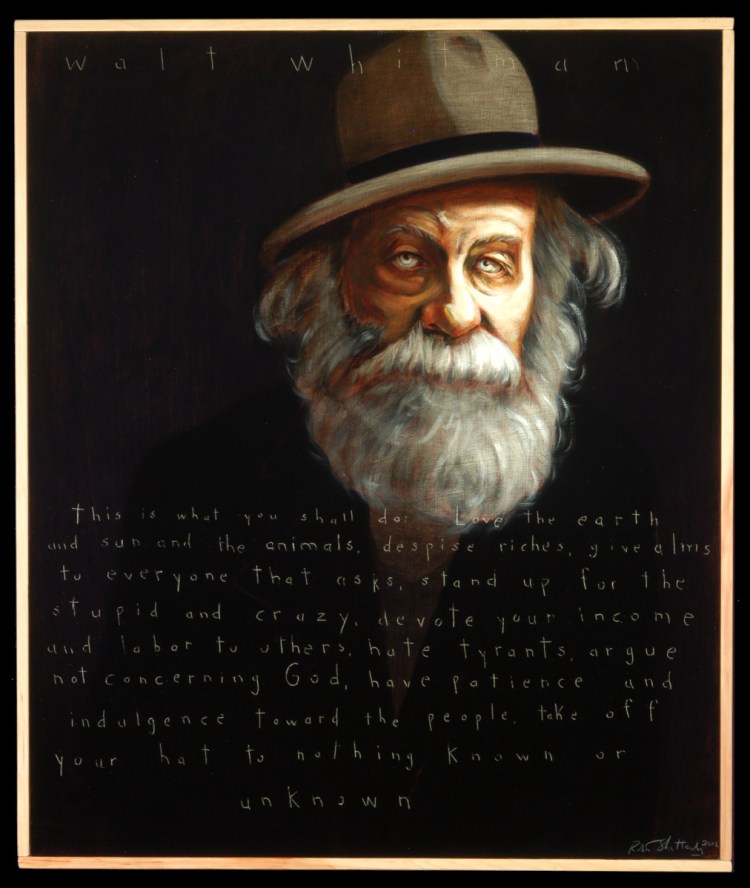

“Americans Who Tell the Truth” portrays citizens who have stood up, often at their own risk and peril, for social, environmental and economic fairness. His first portrait was Walt Whitman. “Uncle Walt saved my life,” Shetterly said. “I was so upset after 9/11 and all this rhetoric starting about Iraq. I was so angry the media was allowing this to happen. They weren’t asking the right questions. They weren’t doing their jobs.”

Shettlerly was seething with a sacred rage, informed by grief, and careening toward unhealthy stress. Feeling helpless, he pondered, “What can I do as an artist and have a voice at this moment and not feel so alienated from my country?”

Years ago, he tacked up on his studio wall a quote from the poet Whitman, from the preface to “Leaves of Grass”:

“This is what you shall do: love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to everyone who asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown.”

He painted Whitman’s portrait as an old man with a bushy white beard and scratched that quote into the surface of the paint. He dressed Whitman in a black shirt and brown hat and set him against a darkened background, with the gray-white of his beard and the soft heaviness of his eyes bumping through the dark.

He felt invigorated. After a conversation with his wife, Gail, he had an epiphany. “I would paint 50 of them and call them ‘Americans Who Tell the Truth,’ and I decided to give them all away. I would not sell a single one of them. That felt liberating. I was totally free of the commercialism of this country and the art world and everything else,” he said.

He blew past 50 and is still researching subjects to paint. Instead of selling his paintings, he makes them available for travel for exhibitions and education, packing them in small groups arranged by themes. He doesn’t sell the paintings, but he gets paid to talk about them, and has spent 17 years traveling the country talking about Americans who make a difference by having the courage to speak the truth.

There’s been one book, now out of print, and he’s won awards. “I don’t make money, but I survive. I keep going,” he said.

His subjects include historical figures in sports, politics and culture, like Muhammad Ali, Susan B. Anthony, Shirley Chisholm, Arthur Miller, Rosa Parks, Woody Guthrie and Dwight Eisenhower, and such contemporary people as Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a public health advocate who helped expose the public water crisis in Flint, Michigan, and Richard Bowen, a former executive at Citigroup who blew the whistle on the sub-prime mortgage crisis. They were among many subjects in the series who attended the opening at Syracuse.

Shetterly remains engaged and feels the same urgency as when he painted Whitman, when his red-hot blood was coursing through his veins. The accumulated lesson of 17 years of defiant and idealistic inclusion is this lesson about America: We all make this country, not just the people with power and money, he said.

“If you are going to be an honest country, you have to include us. And the process by which we achieve inclusion is not the democratic process we are told to participate in all the time, which is every two years. Most of the most democratic work in this country has been by people willing to work outside of that, through civil disobedience or by whatever means necessary.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story