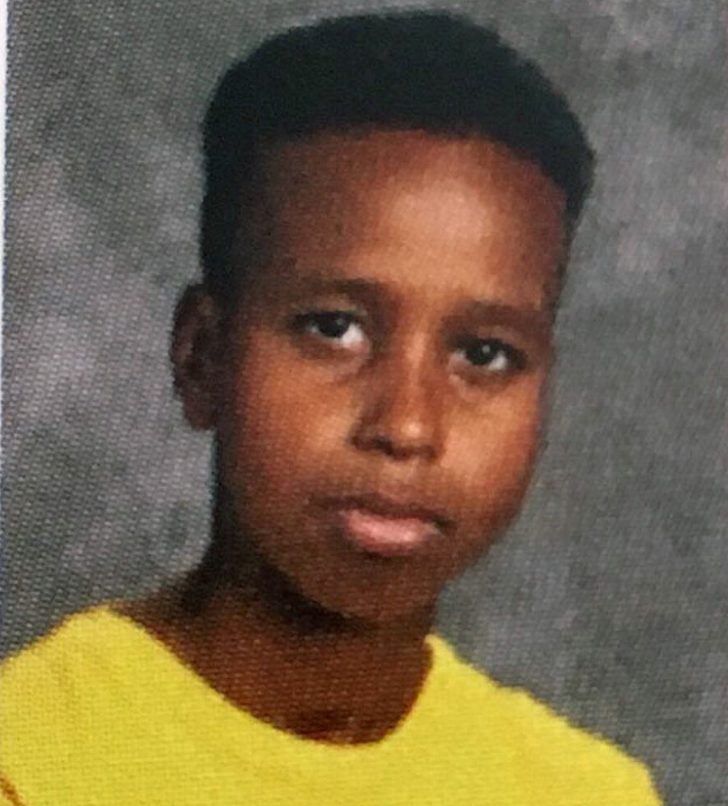

LEWISTON — Neither the adult chaperones nor the lifeguard at Range Pond State Park saw Rayan Issa in distress or struggling in the water when he drowned during a Lewiston Middle School outing on June 12, according to a report conducted for the Lewiston School Department.

However, students playing football in the water with Rayan reported seeing him go after the football into deeper water, then struggling for about 30 seconds before he went under and did not come back, according to the report commissioned by Superintendent Bill Webster.

The report, which was released Monday night, does not indicate if or how quickly those students reacted. On Tuesday, Webster said that he could not answer those questions because he had not talked to the report’s author, Lewiston attorney Daniel Stockford of Brann & Isaacson.

The report states that a student who told a teacher “he could not find Rayan” did not seem to have a sense of urgency, and other students began to speculate to the teacher that Rayan could be in the bathroom.

Because that teacher understood the boy could be in the water, she immediately went to get the lifeguard 100 yards away and notified other chaperones that the boy was missing, the report said.

On Tuesday, Webster also issued a directive that prohibited swimming on all school field trips. He said the policy is necessary because the school district does not currently have a way to determine whether a student can swim. The directive takes effect immediately because the school department’s summer learning programs begin Monday, he said.

Webster’s directive also mandates that all field trips must be approved by the school committee before permissions slips are sent out, and all permission slips will be in English and Somali.

He expects that the school board will adopt a permanent policy governing field trips to replace his directive before school starts in the fall.

Androscoggin Sheriff Deputy Chief William Gagnon said Tuesday that his department’s report is not complete and that its investigation is ongoing.

Stockford’s report is Part I of the investigation, given to the Lewiston School Committee on Monday night.

Part II is not complete, and will focus on best practices about field trips that involve swimming. Those best practices are being developed with an expert on water safety.

The report’s preliminary conclusion is that the Lewiston Public Schools should change its policies and establish specific standards for field trips that involve water activities.

Until the school committee adopts a district-wide policy, Webster’s directive requires that permission slips also include more in-depth information about each trip, including a list of all possible activities, any and all risks associated with those activities and a description of the safety steps and precautions that will be used.

Additionally, all field trips will begin with a safety talk, employ a buddy system, and include regular check-ins.

GREEN TEAM TRIP

The report paints a picture of a day planned as a fun, end-of-the school excursion, but that quickly turned to confusion and then tragedy when Rayan went missing.

Once the word spread that Rayan’s whereabouts were unknown, a 911 call went out at 11:47 a.m. Rayan’s body was found by Poland firefighters at 12:17 p.m. within the roped-off area, according to the Androscoggin County Sheriff’s Office.

In preparing the Brann & Isaacson report, all 11 adult chaperones were interviewed, as were five students.

The field trip was organized by the seventh-grade Green Team at Lewiston Middle School, which had taken a similar trip to Range Pond the year before.

The school’s team leader made an advance reservation with Range Pond State Park. Of the 138 students in the Green Team, 111 attended with 11 adult chaperones. The 11 adults all work for the school department, and included six teachers, a teaching coach and three ed techs.

The ratio of 10 students to one adult chaperone exceeded the Lewiston School Committee’s policy for middle school field trips, which requires there be one adult for every 15 students.

On June 12, students and chaperones arrived at Range Pond about 9:30 a.m. They met to discuss ground rules, which included students must listen to teachers, staff and lifeguard; be safe in the water; stay within the roped-off area; and have no horseplay in the water, according to the report.

Individuals interviewed for the report said no safety talk was given to the group by any Range Pond State Park employee, which contradicts a spokesman for the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, who has said the group was given a safety talk.

After visiting the changing area, the group went onto the beach, where there was one lifeguard. Students were allowed to go into the water, and chaperones arranged chairs or towels so they could watch students on the beach and in the water, according to the report.

TEACHER: ‘HE MAY BE IN THE WATER’

The tragedy unfolded “sometime after 11 a.m.,” the report said, when “Student A” called out for the team leader.

The teacher went to the student, who told her “he could not find Rayan.” The teacher tried to determine where Rayan was last seen. Answers she received from students were confusing, the report said.

At the time Rayan was reported missing, there were six chaperones on the beach watching students – the team leader and five other educators.

“Neither the adult chaperones nor the lifeguard observed the student in distress or struggling in the water,” the report said.

When the lifeguard was told the student was missing and could be in the water, he began looking for the student through his binoculars. “Chaperone A” asked the lifeguard to go to the area where Rayan was last seen, the report said. The team leader was also in the water looking for Rayan.

The report said the chaperones on the beach “took action when Chaperone A reported that Rayan had been reported missing.” The team leader went to the group of students with whom Chaperone A had been speaking and got clarification that the students had last seen Rayan in the water.

WATER GOT TOO DEEP

All of the students were ordered out of the water. They were lined up so “attendance” could be taken. The 110 students were then instructed to go to the shelter off the beach. Some chaperones went with them, others stayed and continued the search, the report said.

The team leader called 911.

According to the report: “The perception of some chaperones at the scene was that the lifeguard was slow in responding. When the lifeguard did not immediately get in the water to search where the student was last seen, one of the chaperones told the lifeguard to get in the water to help the team leader search.”

The lifeguard called for help from another park employee, and directed adults who could swim to help with a water search. The lifeguard organized five adults to do a water search, which involved them locking arms in a line, sweeping their feet. While doing that, the water got too deep.

“There was a sudden drop off in depth that put the water over their heads,” the report said.

The lifeguard then instructed adults to attempt a deep-water search by diving.

When the first rescue unit from the town of Poland arrived, Poland firefighters asked to speak to the students who had last seen Rayan. Three students were brought to the beach to show where they last saw him.

At 12:17 p.m., rescuers found the boy in the water.

“Efforts were made to remove the three students from the beach as quickly as possible,” according to the report.

Rayan was placed in an ambulance and rushed to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.