CR Lawn weathered the infamous blizzard of February 1978 in his uninsulated cabin in Canaan. He had no running water and just a wood cookstove to keep him warm. He was young and sturdy, but also sensible enough to think that maybe the next winter he’d rather not sit in that cabin wondering if the walls might blow in.

He lived fairly hand to mouth, particularly in the many Maine months when his gardens lay fallow. He’d make $20 every time he’d make a run down to Chelsea, Massachusetts, for the Maine Federation of Cooperatives, a group that used collective purchasing power to buy and bring back good cheese, oils, bread and produce from the Boston area and then divvy it up among its members. The cooperative went by the abbreviation Fedco, which Lawn thought sounded like something out of George Orwell. (“Orwellian” is a term he uses regularly.)

But they had a warehouse and an office with heat. Lawn made a suggestion to Fedco. In exchange for letting him sleep in the warehouse, and paying him a small amount ($75), he’d come up with some special projects for the co-op.

He had no idea at the time what these special projects would be, only that they might get him out of the cold.

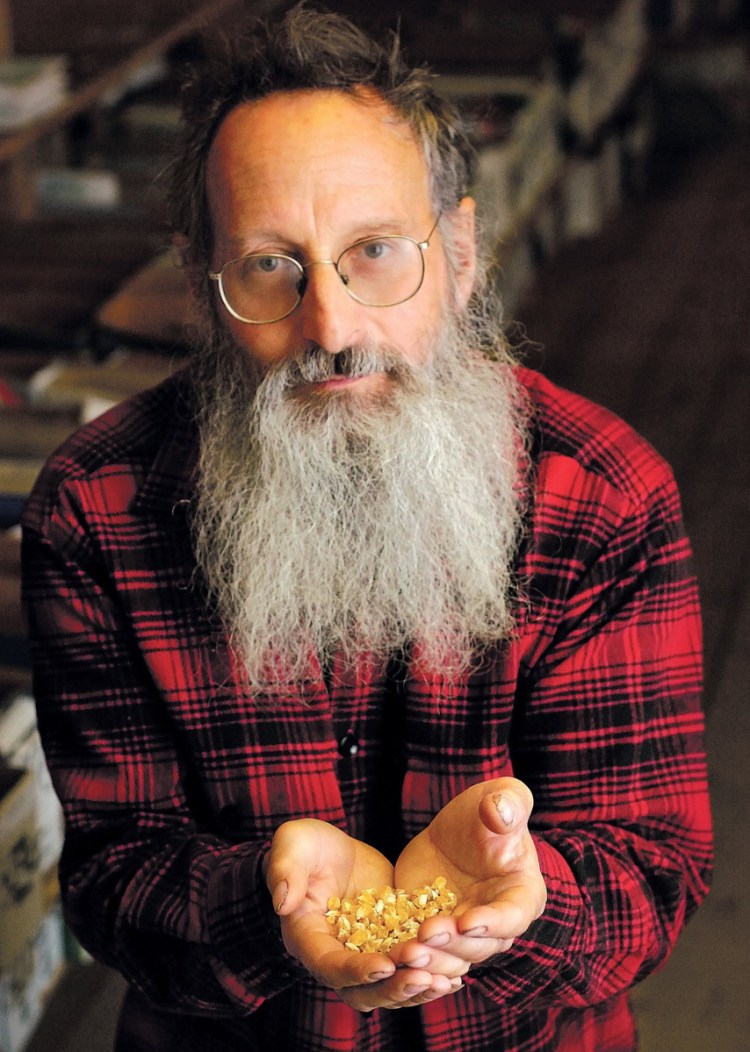

One of the ideas he came up swallowed all the others. It was a seed-buying cooperative, which ultimately became Fedco Seeds, a Maine institution right up there with Johnny’s Selected Seeds and the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association. This May, 40 years after he came up with the idea partly to justify hiding out from the cold, Lawn, who will turn 72 on May 5, is retiring from Fedco.

Today Fedco swells to a staff of about 75 during peak season (March and April), sells to growers in 50 states, although most are in the Northern states, fills roughly 34,000 orders worth about $5 million annually and deals in bulbs, tubers, trees, perennials, books and supplies as well as seeds. (Fedco also offers a grass seed mix called CR Lawn, an all-purpose blend of bluegrass, red fescue, ryegrass and white clover, which can be purchased in bags starting at $22.50.)

All that from a young hippie with a green thumb trying to find shelter from the next big winter storm.

THE GRASS GROWS GREENER

Born Paul Nathaniel Lawn, Lawn grew up in Vermont and upstate New York, the son of parents who began homesteading in the 1940s. (His father took a teaching job after they found they needed an income.) Lawn picked up his nickname – CR stands for Crabgrass – his freshman year at Oberlin. He told classmates the story of his successful bid for student council president in high school, when he’d used the slogan, “the grass grows greener on Paul’s Lawn,” and they dubbed him Crabgrass. It stuck, fittingly, he says, given that he devotes so much time to trying to eradicate his namesake from his gardens.

The first year Lawn farmed in Maine was in 1973. He was 27, and had visited Maine a couple of years before with a friend from Yale Law School (not Hillary Clinton, although she was a first year when he was a second year, and they did chat regularly).

He had finished up his law degree in May 1971 and decided not to go into the legal profession about five minutes after receiving it.

“I didn’t want to dress like a lawyer,” Lawn said. “I didn’t want all the stress of that kind of life.”

He spent nine months in Colorado, living off $300, then returned East. Like his homesteading parents, he wanted land, “and Maine still had bargain prices.”

At the end of 1972 Lawn and some friends paid $4,000 for 60 acres in Canaan, about 10 or 12 of it already cleared, he said. With a well. “One of the last great bargains,” Lawn said.

It rained 47 out of the first 60 days of the growing season.

“I thought I had made a horrendous mistake,” he remembers. “I went to my fifth college reunion mostly to see if everybody else had made such foolish blunders.”

But the next year’s growing season was the kind that made him want to stick around.

The law degree came in handy when he was making that offer to Fedco to live in the warehouse and undertake special projects. So did his accounting and bookkeeping skills. Or what he describes as “these weird skills where I can do mental math” and others describe as almost a “Rain Man”-style phenomenon.

“He doesn’t see numbers the way you and I do,” says Gene Frey, who joined Lawn at Fedco Seeds in its second season, and worked beside Lawn for 39 out of his 40 years at Fedco. “He handles numbers more like objects than numbers. He can add them faster than I can type them into a calculator. That is part of what made Fedco work over the years.”

“His penchant for numbers is a source of joy for a reporter,” says Jean English, editor of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener. “He can tell you that in 1982, at Fedco Seeds’ first appearance at the Common Ground Country Fair, it sold $158.10 worth of seeds and five T-shirts, and at the 1999 fair, ‘Fedco had sales of exactly $15,325.04.’ ”

HUNKERED DOWN IN HALLOWELL

Lawn is also good with the big picture, said Heather Spaulding, deputy director of MOFGA.

“He is an amazing visionary,” Spaulding said. She met Lawn when she joined MOFGA in 1997, and was working on the Common Ground Country Fair. Lawn was on the board – she described him as having been “in every role you can imagine at MOFGA” – and provided invaluable support in helping MOFGA stick to its ideals as the fair was growing.

“He never intended to be provocative or intentionally play devil’s advocate, but he wanted us to consider all aspects of a challenge,” Spaulding said. Lawn’s emphasis was on MOFGA staying true to its Maine roots, and its educational mission. She came to depend on him, particularly as MOFGA worked toward its goal of creating a permanent home, and education center, in Unity.

“He really helped us figure out that path,” she added.

He had the confidence that comes from turning an idea into an institution. Back in 1978, Lawn had mulled plans for those special projects he’d promised the Maine Federation of Cooperatives. Maybe something that tapped into his passion for plants (and bargains). He’d been part of a buying club in Clinton and Canaan called Bilbo’s Birthday (named after someone’s cat) that put together a bulk seed order. What if he turned that into a statewide venture?

From the cooperative’s warehouse in Hallowell, he walked over to MOFGA, which had its office Hallowell then, and asked for the group’s mailing list. Those proponents of organic agriculture probably wanted cheap seeds too, he reasoned.

He wanted this new venture to be inclusive. The food co-op known as Fedco required membership and constant collaboration. Lawn had his doubts about the longevity of that, with people voting on every decision (and bickering, Lawn once referred to these meetings as “dreadful”). Making the seed club open to anyone who wanted to place an order would make it more durable. He was right; the food co-op went under by 1984, but Fedco Seeds lived on.

In the early days, the principle was simple: ask people to submit their requests, make a giant buy and then separate the orders out into smaller packets for distribution. The whole process took just a few weeks. At least it did back then. Frey’s first major contribution, after joining the team packaging up envelopes of seeds, was to suggest a special instrument: a tape gun. Money was tight, though. “CR needed to accompany me to buy this tape gun,” Frey said. He wanted to make sure his $13 was well spent.

“I am a little bit of a control freak,” Lawn says.

For Fedco’s first two years, every seed came from Johnny’s Selected Seeds, which itself was just a few years old. (Rob Johnston Jr. founded Johnny’s in New Hampshire in 1973 and moved it to Maine in 1975). In the third year, Lawn started looking to wholesalers. He checked the bags from Johnny’s and figured out where they came from (most seed farmers in the United States are in Oregon and Washington state) and began ordering directly.

Did that lead to a rivalry with Johnny’s? “There were some moments,” Lawn said. But Johnston taught him a lot, Lawn said. “And he has the best wry sense of humor I have ever encountered in my life.”

Whereas Johnny’s had a centralized location in Albion to do trials, Fedco relied heavily on a decentralized system to do its trials, farming out many test seeds to growers in the state. Lawn did some of the trials in Canaan.

He took it very seriously, so seriously that Frey said if you helped yourself to a zucchini from the garden, you had to weigh it and then log its weight and quality. Lawn had spiral-bound notebooks filled with notes on everything he and the friends he farmed with had grown and picked. They ate almost everything raw and unadorned, except pumpkins, to avoid complicating the flavors.

“We had a rating system for flavor,” Frey said. “One to five.”

The gift for numbers came in handy when they were assessing say, a new variety of peas, which they grew in the kind of abundance that yielded 90-pound harvests every three days for six weeks. “He’d count how many peas in a pod and then do an average,” Frey said.

Tomatoes were (and are) Lawn’s passion. He’d grow 50 varieties in a season, saving seeds in the fall. Still, Maine isn’t a great place for producing seeds, Lawn said. It’s too wet, which can lead to fungal diseases, and also, the growing season is so short. Today, Fedco relies on 70 to 80 seed growers from all over the country.

CR Lawn, speaking at the Common Ground Country Fair in September 2000.

GROWTH SPURT

As Fedco grew and added a tree division in the early 1980s and then hosted a wildly popular annual spring tree sale, Lawn enjoyed playing human cash register, entertaining customers by adding up numbers in his head. “I would put on a show.”

“The only thing we couldn’t get out of him was a receipt tape,” said Kip Penney, a longtime Fedco employee who coordinates the bulbs and seed garlic branch, another 1980s addition.

But by the 21st century, Fedco was too big for such tricks. It doubled in size between 2005 and 2010 – recessions can be very good for seed sales – and it was unreasonable for one man to do all its math. “When it was small, I could have my hands in all the different pies,” Lawn said, a little wistfully.

Fedco operates on a cooperative system not unlike the one used by outdoors retailer REI. You don’t have to be a member to order from Fedco, but since 1985 the ownership has been a hybrid, divided between 60 percent consumer members (there are over 1,100 of them, who pay $100 to join) and 40 percent the worker members. Profit has never been the primary goal, but when the co-op makes one, it may either go back into the cooperative or be divided proportionally via patronage dividends. A 12-member management team oversees Fedco, and Lawn has informally served as the chief financial officer.

But he’s been a CFO with a distinct lack of interest in capitalism. Or change. When Fedco started offering an online catalogue for instance, Lawn wasn’t particularly pleased, Frey said.

“I still think his heart is with the print catalog,” Frey said.

“It’s been pretty stressful the last four or five years,” Lawn said. Fedco hadn’t kept up with some of the needed elements of growth, such as personnel policies, he said. “We were at the awkward stage where you suddenly need a lot of middle management.”

There were debates over spending money. Lawn, so watchful over Fedco’s first $13 expenditure for a tape gun, never stopped being cautious.

“He is very thrifty,” said Penney. “He doesn’t want to spend money. But sometimes a 40-year-old organization needs to spend money. We have to balance that with, do we really have to buy that? Do we really need that set of ladders? That has caused conflict with the younger generation not necessarily being of the same mentality.”

The growing business also meant more hours, and Lawn was less interested in being in an office. He met his future wife, Eli Rogosa, the founder of the Heritage Grain Conservancy, in 2000 at back-to-back organic conferences. They share a house in Colrain, Massachusetts, where she has a bakery that specializes in einkorn wheat and other gluten-safe grains. Lawn likes Colrain, which he points out, has fewer of “the notorious black flies,” plus a longer growing season. After many years of dividing his time between Maine, for Fedco, and Colrain, for farming, he had already started to feel an urge to spend more time in Colrain when he had a health crisis last summer.

In the midst of cleaning out a cat-infested house in Long Island that he and Rogosa are renovating, Lawn pushed himself too far. “I overdid it,” he said. He didn’t wear a mask or gloves. He spiked a fever. When it hit 105, his friends and neighbors called 911. “I was too sick to know what was happening,” he said.

He spent eight days in the hospital with pneumonia. “I was lucky to be alive.”

So once again, Lawn decided to cut back on stress. It was time to give up his work at Fedco. Now it is up to Fedco to evolve without its founder, whose contributions were enormous, but often behind the scenes. “A lot of the work he did was quiet work,” Penney said. “He was really good at doing it on his own. But that has to be spread around.”

Fedco employees are “trying to figure the scribblings” of Lawn’s four decades worth of keeping track of a seed company in notebooks, he said. As Penney puts it, there is a real fear of “founderitis.” Which is? “The disease of founders not being able to pass on everything they know,” Penney said.

“As people like CR leave, the next generation has to learn and grow,” Penney said. “That is a transition that is going to be rugged. And now we are having to learn a lot. Some people are having to learn a lot that they didn’t know they had to learn.”

Mary Pols can be contacted at 791-6456 or at:

Twitter: MaryPols

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story