The 2018 “Portland Show” at Greenhut Galleries is not only the strongest “Portland Show” in years, it is one of the most muscular exhibitions of painting in the area in quite some time. It’s a huge show featuring scores of artists coming together on the theme of Maine’s leading city.

To be sure, a place like Portland with its storied history of landscape and scenic painting might seem a conservative gathering point, but painting is very much alive and well in Maine. It is hardly a stodgy tradition mired in cliche; and this show – the ninth biennial in the series – reminds us, it teems with life, energy, observations and ideas.

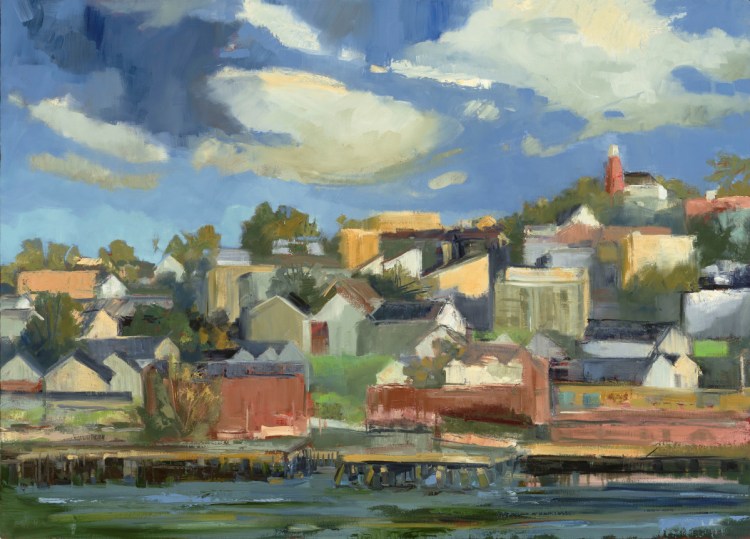

Even the traditional subjects in the “Portland Show” quiver (or even shiver) with life. Philip Frey’s “Patterns of Lobstermen” is a large, pulsingly colorful homage to the rhythms and presence of the signature aspect of Maine’s working waterfront, and Alec Richardson’s “Same as Ever” is a gem of a scene of the lobstermen heading out, even when the temperature had been 10 degrees below zero for days on end. It is an image of respect, even awe, in real time: this season, this year. Henry Isaac’s large “Portland Harbor” bristles with loose painterly power; it’s signature Isaacs – frosting thick and rippling with summer-joyed tones – but with the long straight streaks of airliner contrails in the sky, we find ourselves in an undeniably contemporary moment.

Considering the emphasis on bravado in city, scene and landscape painting, one might expect men to dominate (or one could at least raise the question if they do), but women painters have at least an equal presence. Tina Ingraham’s “Playground Eastern Prom” is a complex and warm narrative canvas that is unmatched in tonal sophistication. Kate Emlen is a new face for me in Maine (although I’ve seen her in Vermont); her “Munjoy Hill” pops with bold forms in a climbing, coherent cityscape. Barbara Sullivan’s intimate fresco “Henry Wadsworth Longfellow House” charms with brazen honesty. Sarah Knock’s “Portland Maine Wharf Reflection” stuns with its water-rippled photorealism, and the artist’s chops have gotten even stronger, so her brush is an impressive presence too. Alice Spencer’s “Lincoln Park Fountain” is almost elegantly severe in its simplified forms, black on white. Nancy Morgan Barnes is undoubtedly one of Maine’s wittiest painters who relies on observation; her “View from the Customs House Parking Garage” appears as a surface-rich bit of cityscape realism, but somehow it gets hijacked by the idea of “a seagull’s eye view” and the invisible smirk can’t be hidden. Barnes is interesting, smart and funny, and she can paint.

Tom Paiement, “Disjointed Discourse Between Two Art Critics,” collage, oil, ink, 27.5 by 21 inches.

History is a major theme of the show as well, and it arrives in many forms. Daniel Minter’s “Young Steward Hallman Cook, Steamship Portland” portrays a crew member of The Portland when it sank on its return from Boston in 1898 with 18 other members of Portland’s African-American community. We see Cook in profile, under a boat form, a clear image of passage and death, but memory and spiritual journey as well. Knit within the bubbling loops of Cook’s chemise is a form of the Abbysinian Meeting House, built by and for the gathering, education and spiritual worship of Portland’s African-American community. The loss of The Portland and its men marked a period of struggle for the supporters of the Meeting House that led to its sale in 1917.

Richard Wilson, “Evening on the Eastern Prom,” oil on panel, 11.75 by 8.5 inches.

Tom Hall’s large and small pair of images of “Easter Morning” feature atmospheric silhouette forms of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception that has dominated much of Portland’s skyline since 1866. Under silver mist skies, Hall, who has lived in the shadow of the cathedral for most of his life, presents the forms as solidly black but somehow ethereally flat on the painted surface. The smaller version features a small cross in the exact center of the canvas, precisely aligned with the horizon. These two works are extraordinary powerful as paintings, and Hall’s ability with a brush is only amplified by the tenor of the works: intense, conflicted and physically impenetrable, despite being emotionally unavoidable.

Thomas Connelly’s “Grand Trunk” is a more straightforward present day representation of a historied building, but the artist digs deep with his atmospheric sense of color to present a portrait of impressive historic depth.

John Whalley’s still life of “Portland Flavors” is a gorgeously detailed meditation on old bottles and how the world even tasted differently 150 years ago.

Daniel Minter, “Young Steward Hallman Cook,” acrylic on panel 30 by 12 inches.

In many ways, the strongest aspect of the “Portland Show” is simply the excellence and range of the paintings. Roy Germon’s masterful color in his boxy wharf-side evening scene, “Jay’s Lot,” takes his already excellent work a notch higher, underscoring why, along with Hall and Colin Page (who is also well represented in this show by a gorgeous Portland panorama), Germon tops my list of Maine painters to watch. George Lloyd’s “Studio Interior, Portland” is a seemingly simple painting, almost shockingly quick with its few, reductive gestures; but Lloyd refuses to sit still. The interior could be an exterior, a topographical representation, a view of the floor, or even a launching point for abstract elements. His skill and decisiveness with the brush has few peers.

Roy Germon, “Jay’s Lot,” acrylic on panel, 14 by 18 inches.

Richard Wilson’s “Evening on the Eastern Promenade” is a small oil on panel, night-lit in the flavor of Linden Fredericks. It features a night that is black but for the silhouette of a house under construction against the midnight blue sky, lightened at the bottom by the setting sun. This blue top is balanced against the orange flash of headlights over the double lines of the foreground road. The entire scene brilliantly turns on the most subtle of passages: A parked van barely appears in the dark at the very center of the painting. Wilson has pulled a brush back over the entire form to reinforce its headlight-reflected fleetingness, as opposed to the slow crepuscular crawl of the darkening sky.

Paul Rickert’s “Evening Arrival” is an overly rare thing: a watercolor in an excellent painting show. In the land of Homer, Hopper, Sargent, Marin and more, watercolors should not be so uncommon. Rickert makes this case elegantly with his horizontal scene of the night arrival of freighter to port.

Paul Rickert, “Evening Arrival,” watercolor 8.5 by 23.5 inches.

The wittiest – and most biting – work in the 2018 “Portland Show” might be Tom Paiement’s “Disjointed Discourse Between Two Art Critics.” It is striking that given his preference to represent Portland as he might, Paiement chose to present Portland as a place where people talk about art. He shows us two men in neckties with their tongues wagging and heads back, almost so that they seem to be staring up adoringly at their own words in the thought bubbles above them. Their words are visual gibberish rendered over collaged print. It’s easy to follow the idea of people talking about art, more to admire their own words than the art they are ostensibly discussing, but the edgy Paiement makes this stick most brilliantly by doing what the critics can’t do: paint.

“Disjointed Discourse” is a masterful work of painted collage: Every stroke of the brush, every fake word, and every scrap of collage hits its mark. And while this might seem a critical work and even a bit mean (though undeniably in the name of fun), Paiement scores his points on the idea that painting isn’t a thing that comes to life in the words of critics or by the comments of complainers or complimenters: The best painting is the product of visual thought, and so the best thinking to appreciate or unpack it is visual, not verbal. For a show loaded with brilliant and well-executed paintings, it’s a worthy point of punctuation.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story