At last, in Lisa Brooks’ commanding, meticulously researched and elegantly readable new book, “Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War,” academics and general readers arrive at something of a fair understanding of the armed conflict between colonial New Englanders and Native Americans.

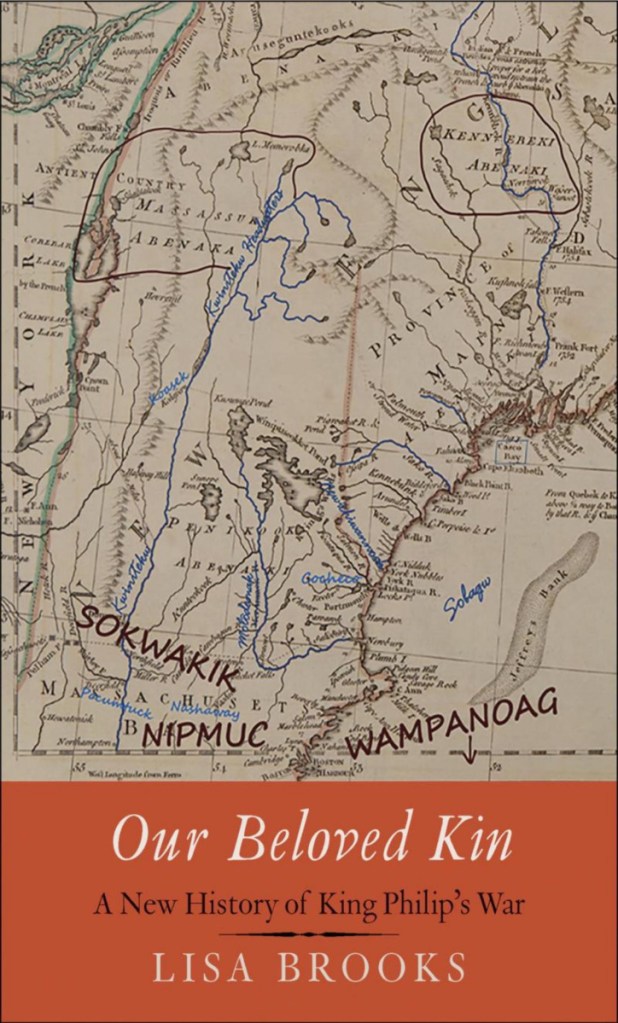

Brooks, a Native American from Vermont, associate professor of English and American Studies at Amherst College and author of the celebrated book “The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast,” builds on scholarship of recent decades, a clear knowledge of geography as well as her own formidable understanding of deeds, treaties and other rarely consulted documents. She introduces readers to individual Native women and men of the 1670s and delineates their lives, tribal homelands and interconnections as never before. Brooks’ enviable use of maps graphically illustrates what proves to be a massive colonial land grab stretching from Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts and New Hampshire to Caskoak (now Portland), where the book begins and ends.

Early colonial chroniclers, including Increase Mather and Nathaniel Saltonstall, termed this action “the war with the Indians of New England” or “The First Indian War” and dated it between 1675 and 1676. It was not until 40 years later, in 1716, in Capt. Benjamin Church’s “Entertaining History of King Philip’s War” that the bloodbath acquired a lofty name; King Philip was the English name for Metacom, a Wampanoag leader. Church, himself an old Indian fighter, put Metacom at the center of the native forces, a “fact” widely accepted until recent years, a way of inflating the chief to hero or worthy rival status. Metacom’s stirring death fed Yankee propaganda mills for centuries.

An aside – I have been wishing for such a book as “Our Beloved Kin” since 1954. It was then that I inherited a copy of “American Hero Stories, 1492-1865” written by Ava Tappan in 1906. The chapter about Metacom cast him as a sort-of hero, an unpalatable blend of fancy, truth, lies, envy, misdirection and Yankee self-delusion that shocked my 8-year-old self:

“The white man’s gun missed fire, but the Indian’s bullet went straight, and the chief fell dead. It would have broken his heart if he had known the fate of his little boy, for the child was sent with hundreds of other captives to the West Indies and sold as a slave. He was the last of the race of Massasoit, the faithful friend of the Englishmen.”

Talk about a whitewash.

For the United Colonies, the killing of Metacom marked the end of the First Indian War in 1676, mission accomplished. For the Native American tribes in New England, it meant the beginning of American slave trade, eviction from their lands and a brutal guerrilla war that would smolder into the 1760s and beyond.

There is so much information, so many ideas contained in “Our Beloved Kin” that it is difficult to know which lines to follow in a short review. One of Brooks’ stand-out points is her discussion of the omission of Weetamoo (Namumpum), the female leader of the Pocasset Wampanoag, from (white men’s) written histories: “An influential Wampanoag diplomat, Weetamoo presented a political challenge to the Puritan men who confronted her authority,” Brooks writes. “Her strategic adaption to the colonial ‘deed game’ enabled her to protect more land than any surrounding leader…”

Though the name Weetamoo appears in numerous colonial land transactions and other documents, she is only a footnote in colonial accounts of war, no doubt because making war on a man, and a king/chief at that, seemed far more noble than fighting a woman. When Weetamoo’s defiled and headless body was found, nobody took credit, attributing it to “God … his own hand.” Weetamoo’s head was stuck on a pole in Taunton. The use of the word “savage” is certainly warranted in this instance, and not for the Native Americans.

Throughout history, individual Native Americans, formerly cast as near faceless or war-painted Indians, assume human form in this narrative. We find such participants as James Printer, a graduate of Harvard Indian School, who was the typesetter for Eliot’s Indian Bible (the first Bible published in North America), and other Native scholars and teachers. A whole generation of literate Christian Native Americans was making its appearance on the scene. Their success was starting to bother many of the leading colonials. In this book – for the first time in my experience – the whole of New England, both Native American and Anglo-American, is displayed culturally and politically, with individual aspirations. “Our Beloved Kin” is a carefully researched, honest and beautifully written book that sets a new balance for the study of New England and North American history.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.” He is writing a history of the Maine Historical Society. He lives in Portland with his wife, Debra, and their cat, Nadine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story