NEW YORK — Should any of this year’s Oscars winners use the occasion to promote a political cause, you can thank – or blame – Marlon Brando.

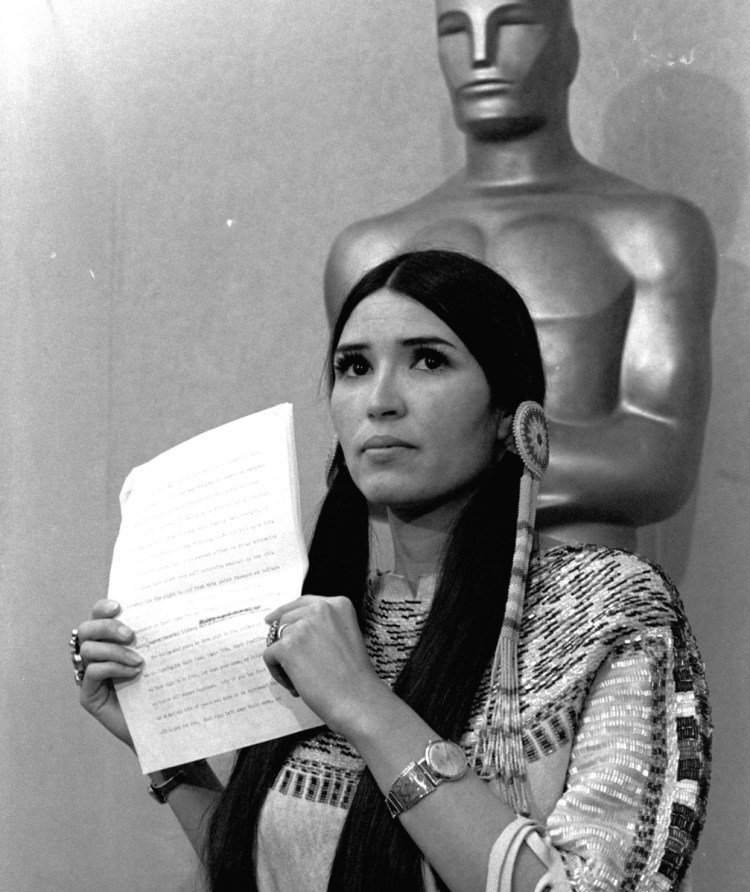

Brando’s role as Vito Corleone in “The Godfather” remains a signature performance in movie history. But his response to winning an Academy Award was truly groundbreaking. Upending a decades-long tradition of tears, nervous humor, thank-yous and general good will, he sent actress Sacheen Littlefeather in his place to the 1973 ceremony to protest Hollywood’s treatment of American Indians. In the years since, winners have brought up everything from climate change (Leonardo DiCaprio, “The Revenant,” 2016) to abortion (John Irving, screenplay winner in 2000) to equal pay for women, Patricia Arquette, best supporting actress winner in 2015 for “Boyhood.”

“Speeches for a long time were relatively quiet in part because of the control of the studio system,” says James Piazza, who with Gail Kinn wrote “The Academy Awards: The Complete History of Oscar,” published in 2002. “There had been some controversy, like when George C. Scott refused his Oscar for ‘Patton’ (which came out in 1970). But Brando’s speech really broke the mold.”

Producers for this year’s Oscars show have said they want to emphasize the movies themselves, but between the #MeToo movement and Hollywood’s general disdain for President Donald Trump, political or social statements appear likely at the March 4 ceremony. Winners at January’s Golden Globes citing the treatment of women included Laura Dern and Reese Witherspoon, who thanked “everyone who broke their silence this year.” Honorary Globe winner Oprah Winfrey, in a speech that had some encouraging her to run for president, noted that “women have not been heard or believed if they dare speak the truth to the power of those men. But their time is up. Their time is up. Their time is up.”

Before Brando, winners avoided making news even if the time was right and the audience never bigger. Gregory Peck, who won for best actor in 1963 as Atticus Finch in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” said nothing about the film’s racial theme even though he frequently spoke about it in interviews. When Sidney Poitier became the first black to win best actor, for “Lilies of the Field” in 1964, he spoke of the “long journey” that brought him to the stage, but otherwise made no comment on his milestone. When Jane Fonda, the most politicized of actresses, won for “Klute” in 1972, her speech was brief and uneventful.

“There’s a great deal to say, but I’m not going to say it tonight,” she stated. “I would just like to thank you very much.”

Political movements from anti-communism to civil rights were mostly ignored in their time. According to the movie academy’s database of Oscar speeches, the term “McCarthyism” was not used until 2014, when Harry Belafonte mentioned it upon receiving the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. “Vietnam” was not spoken until the ceremony held April 8, 1975, just weeks before North Vietnamese troops overran Saigon. No winner said the words “civil rights” until George Clooney in 2006, as he accepted a supporting actor Oscar for “Syriana.” Vanessa Redgrave’s fiery 1978 acceptance speech was the first time a winner said “fascism” or “anti-Semitism.”

Political or social comments were often safely connected to the movie. Celeste Holm, who won best supporting actress in 1948 for “Gentleman’s Agreement,” referred indirectly to the film’s message of religious tolerance. Rod Steiger won best actor in 1968 for the racial drama “In the Heat of the Night” and thanked his co-star, Poitier, for giving him the “knowledge and understanding of prejudice.” The ceremony was held just days after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whose name was never cited by Oscar winners in his lifetime, and Steiger ended by invoking a civil rights anthem: “And we shall overcome.”

Hollywood is liberal-land, but the academy often squirms at political speeches. Redgrave was greeted with boos when she assailed “Zionist hoodlums” while accepting the Oscar for “Julia,” a response to criticism from far-right Jews for narrating a documentary about the Palestinians. She was rebutted the same night: Paddy Chayevsky, giving the award for best screenplay, declared that he was “sick and tired of people exploiting the Academy Awards for the propagation of their own propaganda.”

Producer Bert Schneider and director Peter Davis, collaborators on the 1974 Oscar-winning Vietnam War documentary “Hearts and Minds,” both condemned the war by name (they were the first winners to do so), welcomed North Vietnam’s impending victory and even read a telegram from the Viet Cong. An enraged Bob Hope, an Oscar presenter and longtime Republican, prepared a statement and gave it to Frank Sinatra, who was to introduce the screenplay award: “The academy is saying, ‘We are not responsible for any political references made on the program, and we are sorry they had to take place this evening.’ ”

In 2003, Michael Moore received a mixed response after his documentary on guns, “Bowling for Columbine,” won for best documentary. The filmmaker ascended the stage to a standing ovation, but the mood soon shifted as he attacked George W. Bush as a “fictitious president” and charged him with sending soldiers to Iraq for “fictitious reasons.” The boos were loud enough for host Steve Martin to joke that “Right now, the Teamsters are helping Michael Moore into the trunk of his limo.”

Sometimes, the academy tries to head off any statements before they’re made. Whoopi Goldberg, host of the 1994 show, hurried out a list of causes during her opening monologue.

“Save the whales. Save the spotted owl. Gay rights. Men’s rights. Women’s rights. Human rights. Feed the homeless. More gun control. Free the Chinese dissidents. Peace in Bosnia. Health care reform. Choose choice. ACT UP. More AIDS research,” she said, before throwing in jokes about Sinatra, Lorena Bobbitt and earthquakes.

The audience laughed and cheered.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story