“Bounty,” the Maine College of Art’s 2016 biennial faculty exhibition is, finally, everything we could want from an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art. The difference is the guiding touch of Sage Lewis, guest curator and 2004 alumna. Lewis has beautifully presented an intriguing slate of 10 artists and enhanced the work of each with a savvy and dynamic installation.

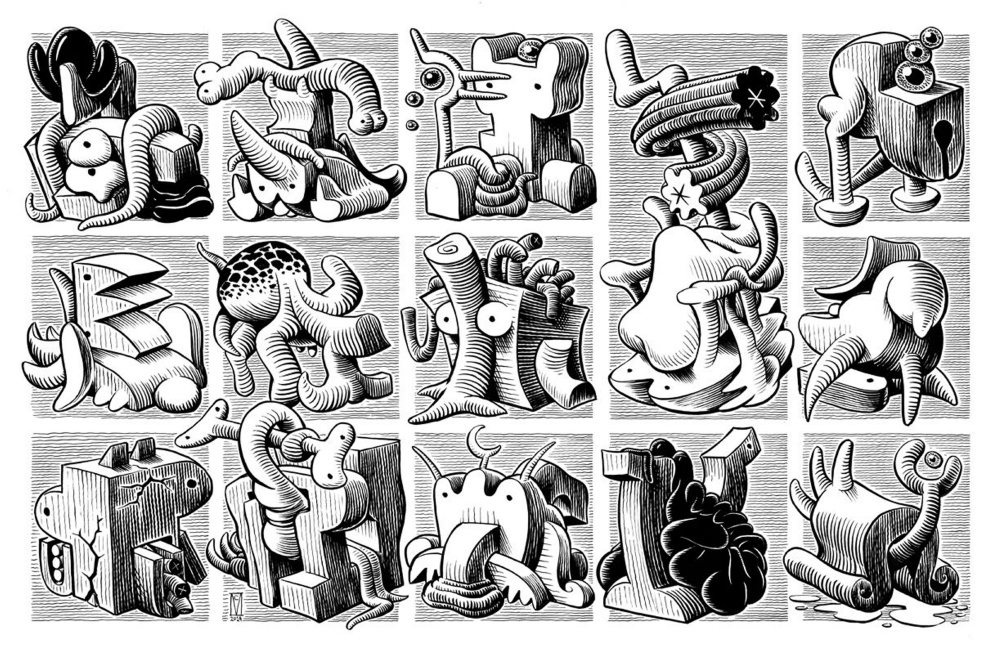

Behind the reception desk is a slick bit of signage of white lettering on an ochre accent wall that announces something a little more grown-up and elegant than usual. The front gallery combines Michael Connor’s graphic novel-style biomorphic mini-monsters multiplying like viral-math rabbits with Lucy Breslin’s old-school-ish ceramic still-life platters, which could pass for drunkenly dreamt leftovers from a Dionysian binge in the arts décoratifs section of the Louvre. Connor’s and Breslin’s works are fun and engaging, but they are more interesting together as they challenge each other on issues of proliferation and indulgent plenty, in other words, bounty.

Setting the scene with art historical bounty is like setting a fancy table for a food fight. Lewis clearly gets that the “still life” – traditionally associated with the idea “nature morte,” or, “dead nature” – is a double-edged sword. “Bounty” follows the American current of indulgent thanksgiving, but it is also infused with a waft of “memento mori,” a Roman reminder that we all have to die. The phrase was originally whispered to triumphant Roman generals, but the practice was pulled into the iconography of bounty (in the sense of good fortune) in Christian culture, the leading example of which was the still life, to remind the lucky that they must always cultivate their humility and preserve the ultimate perspective that death and judgment await all.

Lewis, however, is hardly launching us into a morbid morality trap. Instead, she sets up a thoughtful journey that pushes past the here-and-now experiential indulgence of, for example, beautiful abstraction, to a cultural long game that includes histories, ethics, self-awareness, environmental awareness and moral philosophy.

In the hall passing from the front gallery to the larger spaces, MECA photography program chair Justin Kirchoff’s large black and white photographs curve off the wall, hung only by a pair of pins at the top. The self-consciously vulnerable photos present landscape – land around a highway access point – as the thing which swallows objects in time. Kirchoff’s “Retread,” for example, is a look down at the oily gravel next to a human-chopped rock cliff, and we see detritus including a bit of tire that initially looks like tree bark and a few empty beer cans that, as intended but against our expectations, are dissolving into the landscape.

Across the hall are three stylized florals by Gail Spaien. Like Breslin’s feminist dishes, these could be lost as straightforwardly decorative in the wrong context, but here they whisper at the bounty of decorative arts that have long been associated with women: florals, needlepoint and so on. Spaien mines the system logic of such crafts just enough that we can admire the cold broadness of her conceptual gesture and her personal ability with a brush. In “Still Life #3,” for example, the hexagonal system of a bouquet in a large interior still life with three vases of flowers and a fiber wall-hanging presses us to consider the impossibility of human repeatability. Spaien leave us with afterimages not of cogs, but of quirk – and the idea that humanity is the relationship between “normal” recognizable culture and the stuff in the margins and the seams.

Joshua Reiman’s 20-minute video is a fascinating blend of literalism and hagiography presented as a video consideration of Yves Klein’s conceptual “Zones of Immaterial Pictoral Sensibility,” a work that involved the French artist’s selling of an empty space on Seine across from Notre Dame at which he would dump gold given to him by the “buyers.” Reiman’s film follows a bow-tied and silent protagonist on a consideration of what happens to minerals dumped into the Seine. Rather than discourse about art, immateriality and conceptualism, the narrative (gorgeously muttered in liquid French with prosaic subtitles) follows an oddly materialist course down the river as the theme, with a few art-worshipping sidelines, and quietly morphs into a naturalist meditation on the state of the Seine. It’s like a filmmaker went to bed as a dreamy Frenchman and, after a night of wild art dreams, woke up as a literalist American.

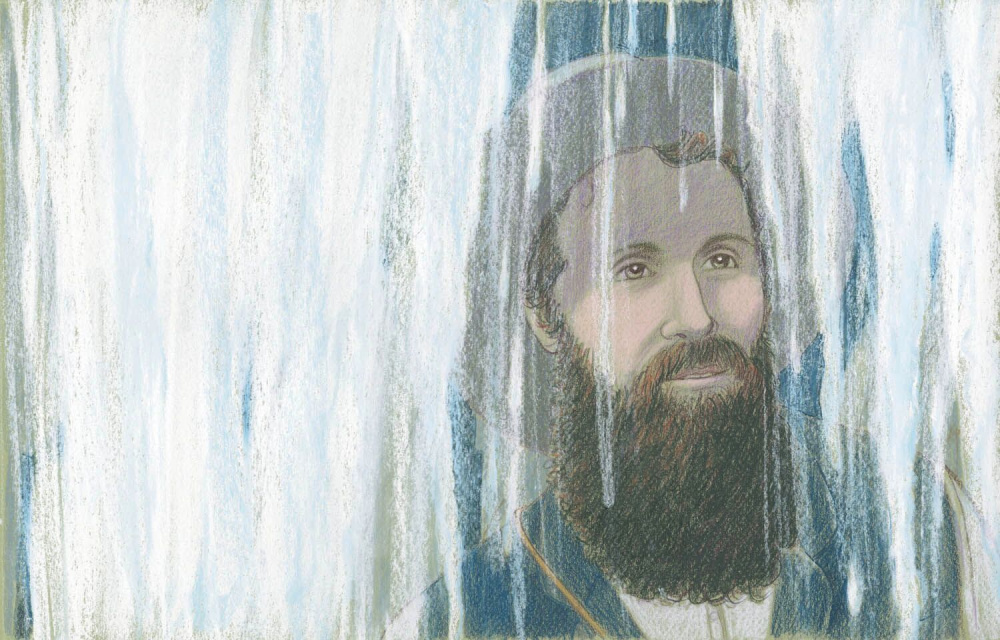

This environmental long game is the crux of Lewis’s bounty. We have great stuff, she implies, so let’s take care of it. We see this in Jamie Hogan’s illustrated book project about John Muir, the great American naturalist. We see it in Kate Greene’s photographs of exploding fireworks that look like eternity itself in the form of the cosmos, but which we sense as what they are – firey explosions – with the effect of compressing cosmic time to the point of inspiring urgency. And we see it in Gan Xu’s paintings of China, his native homeland which has conflicted him by toxic political and environmental landscape; his paintings of Monet’s Giverny are serenely unconflicted, while a photograph confirms that the Xu has radically edited his paintings of China.

Julie Poitras Santos’ installation of hanging lights, droning voice and oddly iconoclastic objects holds the center of the ICA’s main gallery with a spare conceptual elegance. The piece is based on Argentine Jorge Luis Borges’s “Library of Babel,” a pre-internet (or should we say “pre-Google”) portrait of a universe – a library that unrepeatably contains every possible text or combination of letters. It’s a soulless place, impossibly sad and bereft of specific form. Whether intended or not, Santos forces the opposite to Borges’s hypothetical universe because we can search for and find meaning from among seemingly infinite oceans of meaningless crap otherwise known as the Internet. By presenting Borges’ information dystopia with no sense of true, we see the bountiful opposite in our world: meaning.

But nowhere is this ironically upbeat possibility more satisfying than in Hilary Irons’ paintings. They are verdant forest landscapes teeming with bustling life and the culture of painting. They are abstractions – pink, decorative and alive. To challenge us into unexpected wakefulness, Irons adds the subversive image of a yellow-lighted staircase interior imagined from the inside by the forest: Just as we dream of idyllic natural landscapes, they dream of us. When her images are contained, Irons looks longingly out of windows to the place of nature, a dream, a goal, a bounty.

“Bounty” is that rare, coherent exhibition that travels as you want to take it. It’s a coup for MECA, and I hope it lights the way for the ICA’s forthcoming exhibitions.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story