While Maine’s voluntary opt-out rate for school-required vaccines remains among the highest in the nation, state records show that up to 400 more Maine grade school children received the measles vaccine in the 2015-16 school year when compared to last year, substantially improving the state’s protection against a measles outbreak.

Public health experts cheered the improved immunization coverage, as vaccines prevent dangerous diseases such as measles, pertussis, polio and chickenpox.

“It’s great to see the vaccination rates go up,” said Cassandra Grantham, executive director of the Maine Immunization Coalition, a group of medical professionals that advocates for vaccination.

Hundreds more were vaccinated for measles this school year while the student population remained steady, representing improved immunization coverage.

Dr. Dora Anne Mills, vice president of clinical affairs at the University of New England, said the 2014-15 measles outbreak that started in Disneyland may have helped persuade parents to get the measles vaccine, but that Maine still has a long way to go to prevent infectious diseases.

“We need to make more progress,” Mills said. “It continues to be a big challenge.”

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention released school-by-school vaccination rates in early June in response to a Freedom of Access Act request by the Portland Press Herald. It’s the second year that the state has released school-by-school rates, and the Press Herald has compiled an online searchable database.

The voluntary opt-out rate represents parents who sign a form forgoing vaccines for their children based on religious or philosophic grounds. Parents whose children have a legitimate health reason to opt out – such as a medical condition like leukemia – can obtain a medical exemption to vaccines.

Maine’s overall non-medical opt-out rate for kindergarten students declined from 3.9 percent last year to 3.7 percent in 2015-16. State-by-state results for 2015-16 will be released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this fall.

Maine was fifth-worst for vaccine coverage in the 2013-14 school year, when kindergarten opt-outs reached 5.2 percent, but has improved since then. Typically, the national median for opt-outs is about 2 percent or less.

High opt-out rates put thousands of Maine children at risk for the return of preventable infectious diseases.

In Maine, parents can easily opt out of vaccines, and the state is among the most lenient in the country for avoiding required vaccines. Other states require that parents jump through more hoops before opting out, such as requiring counseling or watching a pro-vaccine presentation, and other states do not permit philosophic exemptions. Efforts in Maine to tighten those rules by requiring counseling with a medical professional before taking the philosophic exemption failed in 2015 after Gov. Paul LePage vetoed a bill. Advocates may be gearing up for another attempt to pass a vaccine bill in 2017.

The voluntary opt-out rates might not seem high – the rates have ranged between 3.7 and 5.2 percent over the past four years. But for vaccines to work most effectively and provide “herd immunity” for those who are most susceptible to infections diseases – such as cancer patients, the immune-compromised, the elderly and infants too young to have received their vaccines – the opt-out rates should be as low as possible, public health experts say.

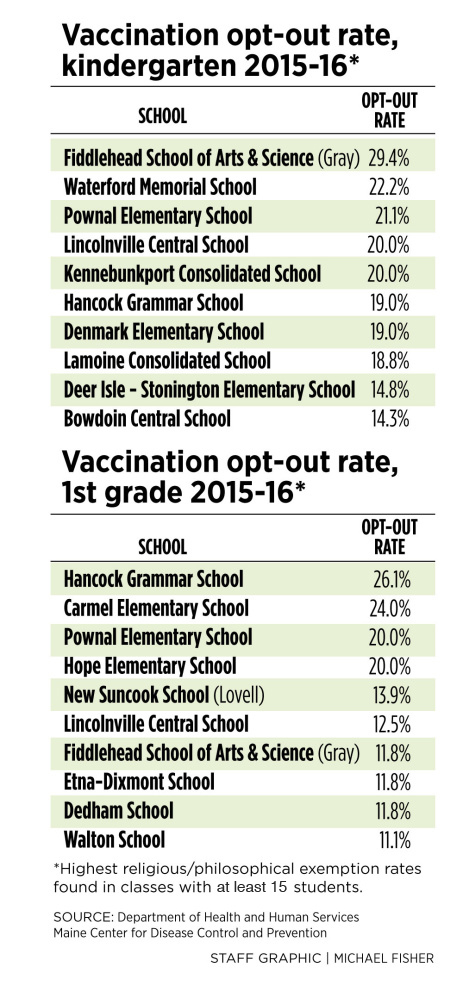

Also, the opt-out percentage is an average, and while some schools reported close to 100 percent vaccination coverage, 40 Maine elementary schools with at least 15 students in kindergarten or first grade have 10 percent or more of the student population forgoing vaccines, leaving those schools most at risk for a disease outbreak.

A few schools reported 20 percent or more unvaccinated kindergartners or first-graders, including elementary schools in Pownal, Hancock and the Fiddlehead School of Arts and Science, a public charter school in Gray.

In recent years, more parents in Maine and nationwide have refused vaccines for their children, in part because of since-debunked theories dating to the 1990s that vaccines were linked to autism. Vaccines are overwhelmingly safe and do not cause autism, according to numerous scientific studies.

Last year, the number of unvaccinated children was actually higher than the reported 3.9 percent who opted out, the records show.

In 2014-15, while Maine’s official opt-out rate was 3.9 percent for children entering kindergarten, the actual rate of unvaccinated children was much higher.

For instance, 968 kindergarten students in 2014-15 reportedly did not have the MMR vaccine – for measles, mumps and rubella – or 7.9 percent of all Maine kindergartners.

Tonya Philbrick, who heads up the immunization program at the Maine CDC, said state health officials last year noticed the discrepancy, that there were hundreds of children who did not have any vaccine documentation – no proof they had gotten their shots and no signed forms opting out.

She said some of the children may have been vaccinated but parents didn’t turn in the forms – so there’s no proof that they received their vaccines – while others may have been unvaccinated. Thirty-nine primary schools in 2014-15 were reporting measles vaccine coverage at 80 percent or worse, alarming public health officials.

Philbrick said heading into 2015-16, the Maine CDC and Maine Department of Education launched a public education campaign for school nurses, Head Start pre-school programs, and the Women Infant and Children nutritional program to emphasize the importance of having complete documentation on immunizations. The Maine CDC tracked records as they came in and made extra calls to schools if it seemed like they were falling behind in turning in the required forms.

All new school nurses were required to attend a training session in Augusta that included a session on vaccine documentation. “I know that what we did (made) an impact,” Philbrick said.

During this school year, there was improved vaccine coverage for not only the MMR vaccine, but also for vaccines for pertussis, polio and chickenpox, the records show.

Philbrick said the CDC does not give any incentives to encourage compliance or impose penalties against schools that do not turn in the vaccine documentation.

Dr. Laura Blaisdell, a Yarmouth pediatrician and vaccine advocate who has been studying human behavior surrounding vaccine refusal, said making the data public and easily searchable could also be making a difference.

Now parents, teachers and school officials can see how their school stacks up against others. There’s a sociological penalty if too many opt out, Blaisdell said.

“With the data becoming public and now transparent, there is somewhat of a consequence, because now people know someone is watching and tracking this data,” said Blaisdell, pointing to studies that show people behave better when they know they are being monitored.

“This allows for an awareness and a dialogue that didn’t happen before. Studies show that when you’re trying to quit smoking, and you tell people you’re going to quit smoking, you’re more likely to be successful.”

In one case, Saccarrappa School in Westbrook improved from one of the worst schools in the state for measles vaccine coverage in 2014-15 to one of the best this year.

In 2014-15, only 80 percent of first-grade students had their measles vaccine, but this year, 97 percent did. No parents signed philosophic or religious exemptions this year.

Brian Mazjanis, Saccarrappa’a principal, said that this year, the school nurse and head nurse for the school emphasized public education for parents on getting their vaccines and turning in their forms. The school also helped parents navigate the system, removing any logistical barriers to providing the school vaccine documentation.

“We really made a commitment to doing this and made it a priority,” Mazjanis said.

Other schools that made dramatic improvements in MMR coverage included Boothbay Regional Elementary School and Small Elementary in South Portland.

Blaisdell said she expects there will be another attempt to introduce a bill that would make it more difficult to opt out of school-required vaccines. She said the improved vaccination coverage that happened by enforcing existing law seems to indicate that there are fewer philosophic objections to vaccines and some of the reason people opt out is because it’s simply easier to sign a form.

“When people are approached by the school, they’re getting their vaccines,” Blaisdell said. “We think that if they’re going to have to go to the doctor to get a consultation, that many would instead just go ahead and get the vaccine.”

Correction: The chart accompanying this story was revised at 10:32 a.m., June 13, 2016, to reflect that the data applies to religious/philosophical exemption rates for classes with at least 15 students. An earlier version of the chart misstated the class size.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story