A rarely discussed component of many employee benefit packages is on the decline, and insurance providers in Maine say they are concerned that the problem is about to get worse.

Providers of long-term disability insurance in the Portland area, a major hub for the industry, say they are witnessing a trend of employers dropping their standard disability insurance plans in favor of employee-paid, optional plans. The result is a higher percentage of employees opting not to participate in the voluntary plans, leaving more workers vulnerable to financial ruin if they suffer long-term illnesses or injuries.

The insurers said employers’ uncertainty about the future costs of employees’ health benefits under the Affordable Care Act is likely to push even more companies to discontinue standard disability coverage for all employees.

“Employers just don’t know what to expect tomorrow,” said Kerry Peabody, senior account executive at Clark Insurance in Portland. “Disability insurance is an easy target.”

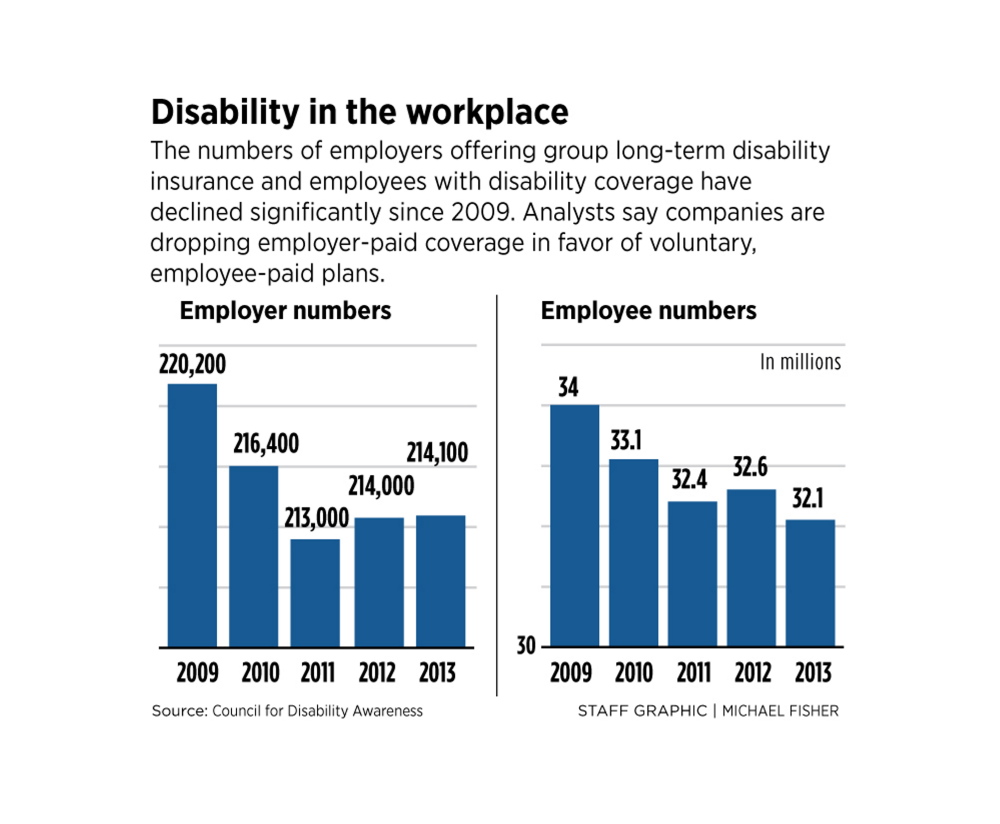

As a result of that shift, the number of U.S. workers with long-term disability coverage decreased from 34 million to 32.1 million – a 6 percent decline – from 2009 to 2013, according to an employer survey conducted by the Council for Disability Awareness, a Portland-based trade group representing disability insurance providers.

During that same five-year period, the total U.S. workforce increased by 6.6 million workers, from 138 million in December 2009 to 144.6 million in December 2013.

The number of employers offering any type of disability insurance plan also fell during that period, from about 220,000 to 214,000, according to the survey.

Another reason for the decrease in covered employees is the trend toward employers implementing “defined benefit plans,” which contribute a set amount of money to each worker to use for insurance coverage. Such plans generally do not cover the costs of health, dental, life and disability, which forces employees to forego some types of coverage or pay more out of pocket.

Only six states and territories require employers to provide disability insurance: New York, California, Hawaii, Wisconsin, Rhode Island and Puerto Rico.

In Maine, which is home to a large contingent of the employee benefits industry, there is no such requirement.

The cost of long-term disability insurance varies between group plans offered by employers and individual plans, which tend to be more expensive, Peabody said.

The rule of thumb for disability insurance plans is between 1 percent and 3 percent of gross annual income, he said. For a 42-year-old nonsmoker making $50,000 a year, the cost of individual coverage would be $1,440 a year, he said.

Depending on the plan, benefits usually kick in after the policy holder has been out of work for three or six months, Peabody said. Individual disability plans pay up to two-thirds of the policy holder’s previous gross income, and the money is nontaxable, he said.

Council for Disability Awareness President Barry Lundquist said the solution to the drop-off in employees with disability insurance is to educate workers about the benefits of such coverage.

To that end, the council has launched a public-awareness campaign and has a website, disabilitycanhappen.org, which contains information about the scope of the worker disability problem and what to do about it.

According to the website, more than one in four 20-year-olds will become disabled at some point before they retire.

Dana Kerr, associate professor of risk management and insurance at the University of Southern Maine, said it is ironic that so many employees choose life insurance over long-term disability coverage.

“The risk of becoming disabled is far greater than the risk of dying,” he said.

Kerr said employees should have both disability and life insurance, even if it means spending some of their own money. But with more employers dropping their standard group disability plans, that just isn’t happening, he said.

The industry has responded to the drop-off in business by setting up private exchanges similar to those created under the Affordable Care Act, he said. The major difference is that the exchanges are for employers to purchase either employer- or employee-paid group plans.

“That’s something that didn’t exist at all until the public (health insurance) exchanges were created by the Affordable Care Act,” he said.

Contrary to the common perception that most disability claims stem from on-the-job injuries, they made up only about 10 percent of all new claims in 2012, according to the Council for Disability Awareness.

The leading cause was musculoskeletal disease (28.7 percent), followed by cancer (14.6 percent), injuries (10.2 percent) and mental illness (8.9 percent), its website says.

A disability that renders an employee unable to work for six months or more can be financially devastating, said David Leopold, senior vice president and chief marketing officer at Unum Group, by far the country’s largest disability insurance provider. The company is based in Tennessee but has a large operation in Portland.

“Your paycheck is your biggest asset,” he said. “You’d be crazy not to have disability insurance.”

Lack of employee disability coverage is bad for employers, too, Leopold said. Statistics show that disabled employees without coverage are likely to take longer to return to work, if they return at all, he said.

“The likelihood of an employee without disability insurance returning to that company is extremely low,” Leopold said.

That causes employers to lose money through reduced productivity and training new workers, he said.

One possible reason for lack of participation is the bad press disability insurance has gotten over the years. Thousands of lawsuits have been filed in the past decade by policy holders who believed their claims had been wrongfully denied, including some high-profile cases that received extensive media coverage.

The shift away from employer-paid plans is a reality that isn’t going away, said Kevin Tierney, vice president of client management and business strategy at Westbrook-based insurance provider Disability RMS.

Therefore, the industry should focus on convincing employees to opt in to voluntary plans, he said.

“The employers, the brokers and the insurance companies want as many people to be enrolled as possible,” Tierney said.

Higher participation is also good for employees because it lowers the cost of group disability plans, he said.

“The higher the percentage of employees that buy voluntarily, the cheaper it is,” Tierney said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story