Maine schools reported that more than 850 students were physically restrained and hundreds were placed in seclusion in the last year, according to the first statewide data on the sometimes controversial methods that schools use to handle out-of-control students.

The information, released Thursday by the state Department of Education, is part of a years-long effort to more closely define what constitutes restraint and seclusion, describe when a teacher is allowed to restrain a student, and spell out mandatory reporting to parents, local school officials and the state.

Educators say that in some cases, restraint or seclusion is needed as a way to give children “time out” periods or keep them from hurting themselves.

Maine overhauled its rules and definitions of restraint and seclusion in the past three years, after a public outcry. Among the changes is a requirement that schools report incidents to the state annually.

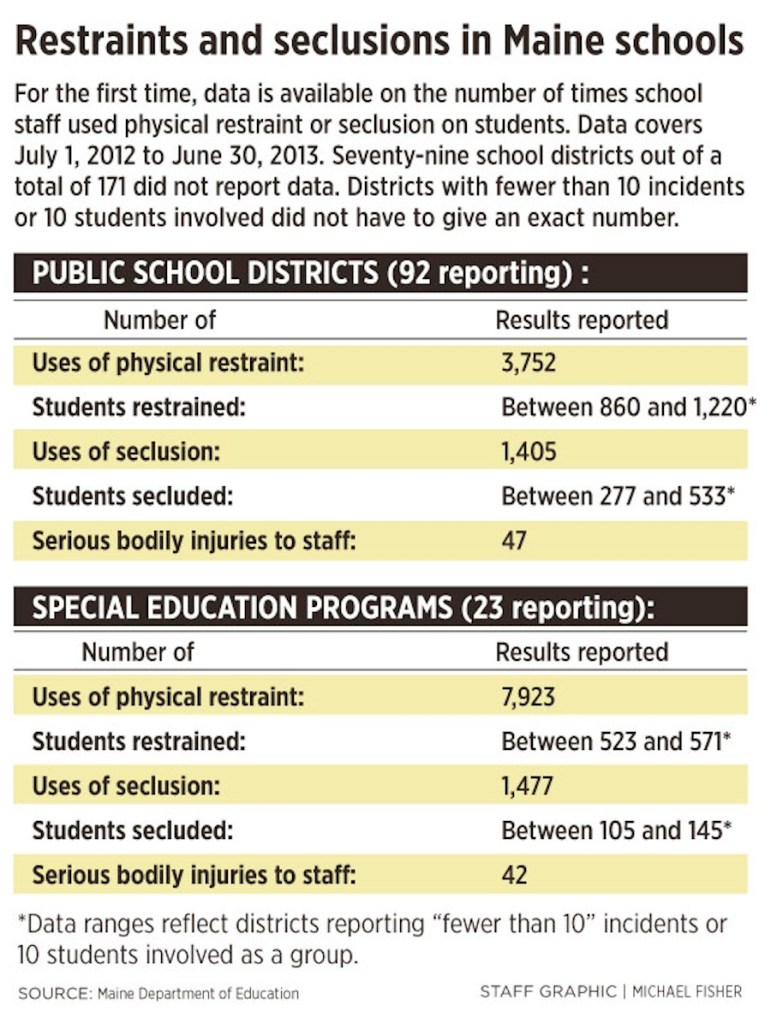

For the first reporting year, which ended June 30, 92 of the state’s 171 school districts submitted data. Among those that did not report are larger districts, including Biddeford.

The districts that did report had 3,752 instances of physical restraint in the past year, involving between 860 and 1,220 students, according to the data.

Those districts reported 1,405 instances of seclusion, involving between 277 and 533 students.

The numbers may be higher because schools with fewer than 10 students involved reported their numbers only as fewer than 10, and were not more specific.

Because the data covers only one year, it’s too soon to draw conclusions from it, said children’s advocates and education officials.

There’s no way to compare the data directly with data from other states, but the handling of out-of-control students is an issue nationwide. More than 30 states have passed laws regulating restraint, and federal legislation has been proposed.

In March, the U.S. Department of Education published a study that estimated there were 38,792 cases of seclusion or restraint in the 2009-10 school year.

Restraint is defined as using physical force to move a student or keep the student somewhere against their will. It can range from giving a flailing student a bear hug to forcing a child to lie face-down on the floor.

Seclusion is defined as a student involuntarily being alone in a specific space, sometimes in a specially designed room with nothing in it that could cause injury.

Maine changed its definition of restraint at mid-year to say it does not include momentarily touching a student or putting an arm around a student’s shoulder to walk them down a hall.

The change may explain why the first set of data varies widely. Some school districts were essentially over-reporting incidents early in the year, officials said.

Regional School Unit 23, which includes Old Orchard Beach, reported 249 restraint incidents with 40 students, and 114 seclusions involving 15 students.

Superintendent Patrick Phillips said the numbers reflect a large district with many students who have behavioral issues, being taught in the legally required “least restrictive” environment.

Also, the district was aggressive in reporting incidents under the new definitions.

The state data separates the numbers for day treatment centers, which serve special-needs students who may be more likely to need restraint.

Those 23 centers reported 1,477 seclusions involving 105 to 145 students, and 7,923 instances of physical restraint involving 523 to 571 students.

MORE GUIDELINES BEING DEVELOPED

The reporting rules were adopted in response to parents and disability advocates who argued that too many children were being restrained unnecessarily and inappropriately.

“These are potentially dangerous interventions and they’re not effective in reducing behaviors,” said Atlee Reilly, staff attorney for the Maine Disability Rights Center, which has advocated for parents and students. “I think people should be asking some questions about these numbers.”

Deb Davis, who is active on the issue and served on a group that helped rewrite Maine’s restraint law, said she is glad that the statewide information is now available. She said she wasn’t told when her elementary school-age son had been restrained, despite multiple meetings with administrators about his behavioral issues.

The data will help parents to know they aren’t alone, she said.

“When this happens to you, it’s very shocking. You feel violated because you feel stripped of your parental rights. … This (data) un-isolates some people,” Davis said.

She is working on another state committee to draw up best practices for avoiding confrontations that lead to restraint or seclusion. The new state data shows the need for such practices, she said.

“These are really big numbers,” said Davis. “If I was a parent, I would have a knot in my stomach, asking why are schools having so many restraints or seclusions for children with behavioral problems.”

Most people in the debate agree that restraint and seclusion are needed to help students in crisis and keep them safe, but there is disagreement about when and how to use them.

Among the complaints in Maine were that parents were not notified of multiple incidents involving their children. Advocates also argued that schools did not have clear and consistent definitions of what constituted restraint or seclusion.

A bill in 2009 to prohibit face-down physical restraint died in a legislative committee. The Department of Education then gathered about 25 educators, children’s advocates and disability specialists, who proposed the changes. It was the first overhaul of the rules on restraint in 10 years.

DATA INCONCLUSIVE BUT USEFUL

Reilly said the new data is not specific enough to allow conclusions. He said a large number of incidents in a district might be concentrated at a particular school, and within a particular program.

That is the case in Lewiston, which had the highest numbers for a school district. The district has a day treatment center for special-needs students in one of its schools, which skewed the numbers because they are reported “by building.”

Superintendent Bill Webster said that of the 449 instances of physical restraint reported in the district, 359 were at the day treatment center.

The Department of Education plans to follow up with schools, said its spokeswoman, Samantha Warren.

“Now that schools have reported this information to us, the department will review and follow up on data that indicates a potential need for technical assistance or further training and continue to work with schools to reduce the needs for these kinds of intervention,” Warren said in an email.

The new data, available at www.maine.gov/doe/school-safety/restraints/index.html, shows how many incidents of restraint and seclusion occurred in each district that reported, and the number of students involved. It also shows whether students or teachers suffered “serious bodily injury.”

Five school districts reported injuries to students, saying there were “fewer than 10.”

A total of 47 staff members were reported as injured.

In special-education programs, two to 18 students were injured and 42 staff members were injured, according to the data.

NEED MORE TIME TO SEE PATTERNS

Portland, the state’s largest school district, reported 77 instances of physical restraint involving 24 students, and 79 instances of seclusion involving 17 students.

In South Portland, Superintendent Suzanne Godin said that, like Lewiston, her district has behavioral programs in the schools that skew the numbers.

South Portland reported 193 restraint incidents involving 34 students, and 144 seclusions involving 18 students.

“Seclusion sounds terrible, but it’s a way to keep a student safe, and a move prior to restraint,” she said. “Some students want that time out so they don’t escalate.”

With so many districts not reporting, the overall data isn’t complete enough to allow any conclusions or comparisons, she said.

“It’s really a snapshot. What we’ll want is to look at data over the next three years and see what is driving that number,” Godin said.

Reilly said the Maine Disability Rights Center is glad that the data is being collected and is broadly available.

“It’s a really good step,” he said, but it will take a year or two to see patterns. “I don’t think this is the sum total of all restraints and seclusions. I think seclusions are under-reported.”

The state overhaul established a new complaint process for parents, who can file complaints with the state if reporting at the local level doesn’t work.

So far, not one has filed a complaint with the state regarding restraint and seclusion, said Warren.

“Hopefully (that) says the local process is being taken seriously and as a result, effectively serving students and families,” she wrote.

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

ngallagher@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story