HARPSWELL — Robert Freson has photographed presidents, kings and queens and a pope.

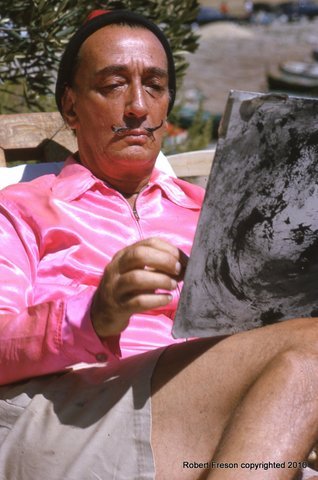

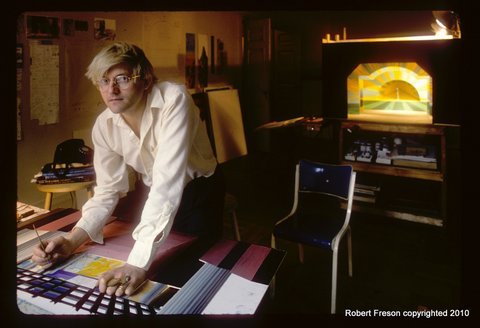

His tally also includes a prince and princess, and the most influential artists of our times: Chagall, Dali, Miro and Hockney.

Now 86 — he turns 87 next month — Freson is busy taking stock of his life and career, bringing order to the half-million or so slides that he has neatly stored in metal file cabinets in the basement of his stately Bailey Island home.

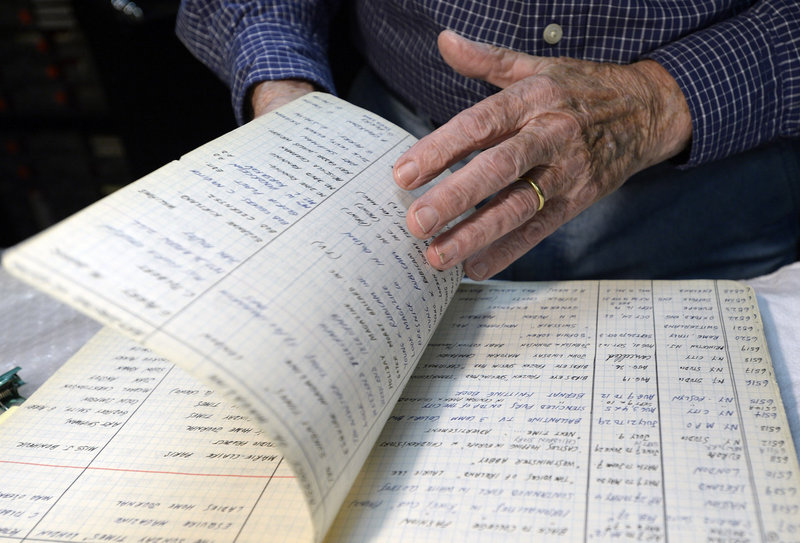

He also has 62 diaries that tell the remarkable story of a man who arrived in United States in 1948 from his war-torn European home with a suitcase, an American wife and $100 in his pocket. He became among the most successful photographers of his time, shooting thousands of images across the world for Look, Esquire and National Geographic magazines, for the Sunday Times of London, and becoming a best-selling author of books about fine French and Italian cuisine.

“It’s been an incredible life,” says Freson, who spent the first dozen years of his professional career working as a studio assistant for photographer Irving Penn in New York. Because of Penn’s reputation as one of the best photographers of his time, that job put Freson in direct contact with the most influential people of the 1950s and 1960s, including Pablo Picasso and then-Sen. John F. Kennedy and the writer T.S. Eliot.

“The quality of the knowledge and culture I had when I first started was as limited as a 21-year-old could be,” he said. “But working with Irving Penn, I met the most famous people of our time. You meet the face behind the names that you have heard, and you get to know them a little bit being with them for three or four hours.”

AWARD-WINNING CAREER

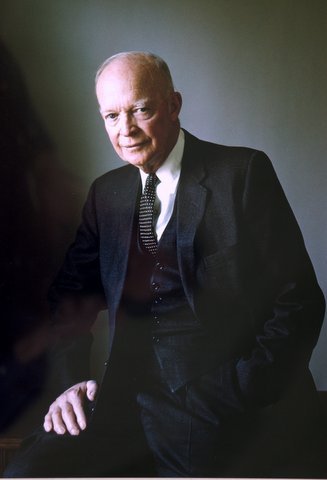

After leaving Penn’s studio, he spent the balance of his career as a freelance photojournalist, creating iconic images of actors Sophia Loren, Omar Sharif, President Dwight D. Eisenhower after he left office, and a host of visual artists.

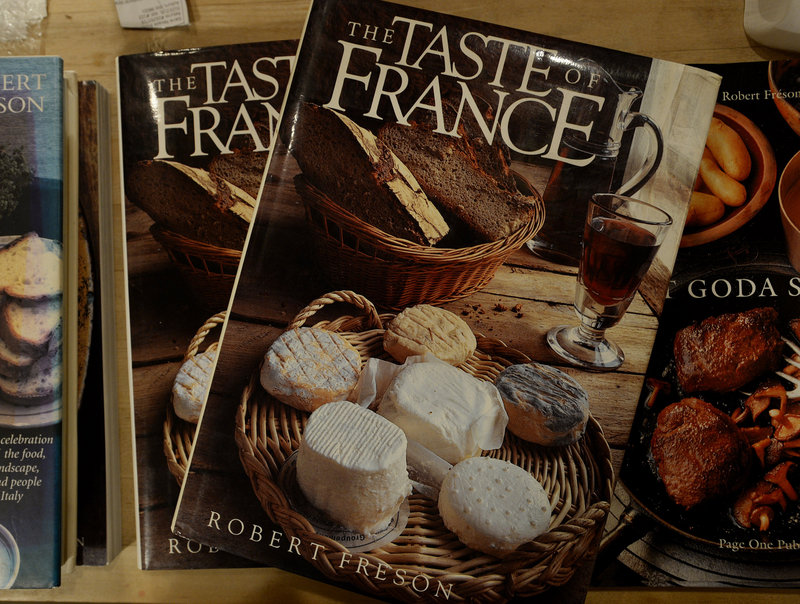

He has won numerous Art Director’s awards for his commercial work, and one of his cuisine books, “The Taste of France,” remains in print and has sold more than 275,000 copies in six languages. It was first published in 1982, and he still receives royalty checks.

He was nearly attacked by an angry communist mob in India and trekked dangerously across the Sahara desert and the Rhub al Khali desert of Saudi Arabia.

He photographed the wedding of Princess Diana and Prince Charles and the funeral of English statesman Winston Churchill. He has photographed Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Noor of Jordan and King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, and Pope John Paul.

He accepted well-paying commercial work to support the work he loved most, which was telling the stories of people and places around the world as a journalist. He views his individual photographs as one long movie. “Photojournalism is a form of cinematography,” he said. “It’s a concentrated film.”

He declines to reveal secrets about the private lives of his subjects, though he will allow that one of his best known images of Sophia Loren is one in which he captured her with a tear running down her cheek. He wanted a shot of her full of emotion at the loss of her first child, and asked her to cry for him. After sending everyone else out of her bedroom, the actress obliged.

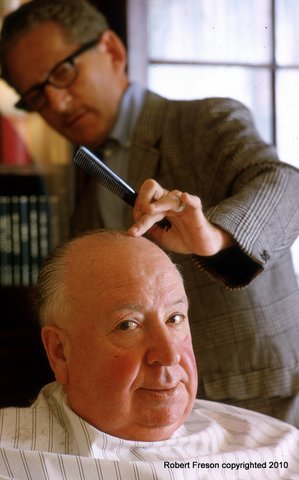

A THANK-YOU FOR EISENHOWER

One of his favorite assignments was photographing Eisenhower in November 1964, three years after Eisenhower left office. The former president wanted a formal portrait for the cover of his book, and tabbed Freson for the job. The two men met at the Eisenhower home and farm, adjacent to Gettysburg battlefield in Pennsylvania.

As a matter of professional conduct, Freson avoided injecting his personal opinion of a subject in his work. He made an exception for Eisenhower. “I thanked him for liberating us,” said Freson, who was born in Belgium and lived there until the German occupation in 1944. Three members of Freson’s family were killed in a bombing raid aimed at German target in France, and he later joined the British Royal Navy.

Eisenhower devised and helped implement the Allied war plan that defeated Germany in World War II.

The two men spent the afternoon together, touring the farm and adjacent battlefield.

“It was just the two of us,” Freson said. “There were no secret services, no public relations people. It was just the two of us. So charming.”

Freson photographed Eisenhower looking straight at the camera, in a heavy black coat, vest and tie, with one hand stuffed in his pocket. Later, he photographed Eisenhower from behind, as his subject walked away.

Eisenhower loved the photo from behind, and suggested that it be used for his obituary. When he died five years later, newspapers across the country used that image.

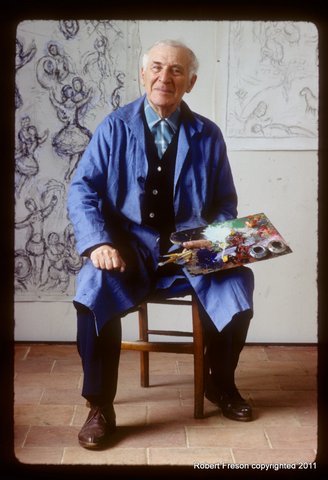

Freson spent three days with the painter Marc Chagall at his village home in France in the mid-1960s. Chagall took him through the house room by room. Freson sensed the artist was shy and protective. Ultimately, Chagall allowed Freson to photograph him in his studio, which was Freson’s desire.

“The way he held the brush, and the way he approached the canvas and integrated with it says a lot about the artist,” Freson said. “The great artists, they all have the natural faculty of seeing anything in life as if it was the first time they’ve seen it. They see things we don’t see anymore.”

Miro, he said, “was a very ‘home’ person. He wanted me to photograph him with his wife, his daughter and his grandchild.”

He assisted Penn on the Picasso shoot. They met at Picasso’s home in France, and at first Picasso was reluctant to allow Penn, Freson and an editor who accompanied them into his house. They had an appointment confirmed, but Picasso hesitated. Only after conferring with a mutual friend who vouched for Penn’s qualifications did Picasso allow the entourage into his private world.

He gave them a brief tour, showed them some recent work and sat for a photo.

THE MOVE TO MAINE

Freson and his wife, Jeannette, spent most of their life in New York City, and lived for many years in France. As they got older, they opted for a quieter lifestyle.

They have lived in Maine since 1998.

“It’s so peaceful here,” Freson said. “It’s much less stressful than living in New York City, especially at our age. Maine is a great resource of culture, and the people here are very honest. I love living in Maine because it gives me time, especially in the winters, which I love. I love the winter because it allows me time to work.”

They bought a seaside home on Library Hall Lane on Bailey Island almost by chance and accident. They came to Maine for a fall vacation. After shopping at L.L. Bean in Freeport, they looked for a nearby hotel on the water.

It was late fall, and most of the seasonal places were closed. But they found a hotel on Bailey Island still open.

They took a room, and the next morning went for drive. Their future home had a For Sale sign out front, and they bought it almost on the spot. They fell immediately in love with the 1892 shingled cottage, which today looks more like a mansion with a magnificent porch and neatly coifed lawn and gardens.

The house itself is brilliant, with high ceilings, large windows that look out to the sea and a delightful kitchen that would charm anyone with a spirit for cooking. “This house sold us, because of the beauty of it,” Freson said.

But the treasures in this house are subterranean. Freson has converted the basement into a near-museum quality storage facility for his slides and his lifetime of work. Every assignment is neatly chronicled in hand-printed ledgers that record time, date, place and subject (Eisenhower, November 1964). Metal storage cabinets are organized by subject (Jamaica Bikinis, Nov. 16-23, 68). A separate room serves as storage for boxes and boxes of props used for his food and fashion shoots.

His goal now is to find a suitable place to leave this trove.

“It’s incredibly difficult to place it, because it is so large,” he said. “I would like to keep it in Maine. I would like to find a suitable institution, like a college or museum. I am not trying to sell it. I am not interested in making money. I just want to make sure it is properly preserved.”

On a recent visit, Freson was dressed in bib overalls, his breast pocket stuffed with pens and two pair of eye glasses. With classical music playing softly in the background, he was mounting and framing color prints that he made in Ireland in 1969. These are images of tinkers — itinerant groups of Gypsies who travel the countryside.

He was preparing the prints for an upcoming exhibition. Although he does not often show his work anymore, Freson still receives requests for exhibitions. This one he is preparing for Loyola University in Maryland. He showed a small sampling of images two years ago at the Frontier Cafe in Brunswick.

STILL SHOOTING

He would love to show more in Maine, and during this visit he received a call from the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Freson wants to meet the museum’s new co-directors. “I want to talk to them about what I am and what I’ve done,” he said.

He remains professionally active. These days, Freson travels to fairs across Maine and takes photographs of animals and their tenders. As he learned from Irving Penn so many years ago, the best portraits are those that capture a subject at ease. “I love people, and I like to photograph people where they are relaxed,” he said.

Despite his accomplishments, Freson does not consider himself a great photographer. He learned from a great photographer in Penn. He’s a good photographer, he said.

What made him successful was his ability to deliver a good photograph under any condition. During his younger years, he worked fearlessly without a hint of intimidation. He knew his task and how to achieve it.

He got the photo at all costs.

“I always came back with a publishable result,” he said. “Editors hired me because I never came back with something a magazine could not use. A photographer must capture a moment. I never gave up.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story