BOOTHBAY HARBOR – They come to Jane Good’s beauty shop in Southport nearly every day to have their hair done and share their fears that the pending closure of the St. Andrews Hospital emergency room could mean their death.

They are Good’s longtime customers, many of whom have been coming to her for decades, now in their 70s and 80s. They come from across the Boothbay region, a 14-mile peninsula, and sit in Good’s salon, attached to her house with a doorway view of her kitchen, and ask how this could be happening.

“They just want to be able to be taken to St. Andrews in five minutes if something goes wrong,” says Good, one of the leaders in the fight to stop the closure. “This whole community is so full of fear, fear that somebody they know is going to die because they can’t get to the hospital in time.”

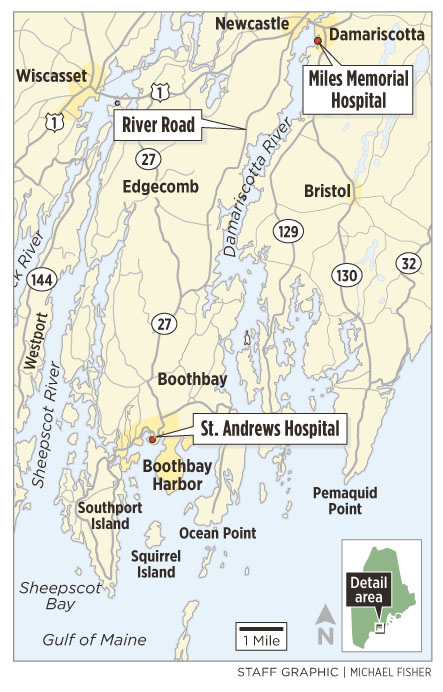

But on Oct. 1, St. Andrews, located five minutes up the road and over the swing bridge in Boothbay Harbor, will cease to be a hospital. Its emergency department will close and 25 hospital beds will disappear. A 10-hour-a-day urgent care center will take its place, but ambulances and emergency cases will be directed another half-hour north to Miles Memorial Hospital in Damariscotta, which is itself being downsized from 38 beds to 25.

The changes were announced just over a year ago by Lincoln County Health Care, the parent entity of the two hospitals, which effectively merged in 2007. LCHC, itself a part of MaineHealth, the state’s largest hospital network, and its board insist it is the only way forward for two rural hospitals pinched by demographics, federal and state reimbursement policies, and declining patient visits. St. Andrews’ bare-bones emergency department can’t provide a safe level of care, they say, and rectifying the situation would be extremely expensive, squandering resources that should rather be spent addressing the community’s other health care needs.

“For many years now, the 24/7 St. Andrews emergency department hasn’t been busy enough to sustain itself from a quality and patient care perspective and secondarily from a financial perspective,” says James Donovan, LCHC’s CEO. “There are better ways to take care of the truly emergent cases than what we are doing now.” The hospital had 4,692 emergency visits in fiscal year 2007, but only 3,770 in 2012, and only a few people each day turn out to need emergency care.

Opponents say Lincoln County Health Care and MaineHealth have betrayed the community’s trust, dismantling a vital institution founded on land donated by town doctor George Gregory in 1908 and nurtured by gifts from local donors and sales rung in by generations of volunteer clerks at the St. Andrews Auxiliary Thrift Store. Since St. Andrews joined MaineHealth in 1996 — and with LCHC in 2007 — they’ve seen the hospital’s services cut back, with general surgery, acute care services and oncology transferred to Miles, part of what some believe was an intentional effort to undermine the tiny hospital’s vitality.

“If they had really sincerely looked at how we could save this and turned over every stone and not found a way, that would be one thing,” says retired clinical counselor Howard Wright of Southport, who served on St. Andrews’ board in the mid-1990s. “But no, their whole viewpoint was to close it down, and to do it drip by drip by drip. … I feel they engineered this for failure.”

A REGION UP IN ARMS

Many of the region’s residents do not accept the argument that the emergency department can’t be made viable, and they have fought the changes since they were announced, mounting an unsuccessful challenge before the office of Maine Attorney General Janet T. Mills. (Mills concluded “there are no legal grounds” for her office to block the changes.) In largely symbolic referendums held in four towns — Boothbay Harbor, Boothbay, Edgecomb and Southport — this year, 86 percent of the region’s residents opposed the emergency room closure.

“It has made a lot of people very angry,” says retired nurse’s aide Helen Farnham, who helped found the local ambulance service in 1975. “Home prices are going to go down, and property taxes are going to go up.”

Over the past two decades, the Boothbay region has attracted large numbers of retirees, many of whom bought with the knowledge that a hospital was close at hand. This helped make Lincoln County the oldest in the state, with a median age of 48.1 years in 2010, compared with 42.7 for all of Maine and 37.2 for the United States as a whole. On Southport, the median age is 60, meaning half the island’s 600 people are older than that.

The sense of betrayal many feel here is augmented by the fact that many thought their hospital had been protected from closure under the original 1996 partnership agreement with MaineHealth. St. Andrews was the first to join the hospital network apart from its founding flagship, Maine Medical Center, and benefited from shared procurement, loan collateral, and insurance pricing with its much larger partner.

The local board took care to ensure that the agreement would give it control of the endowment and would commit MaineHealth “to maintain at a minimum emergency services, outpatient health care services and appropriate home health and long-term care services in the Boothbay Harbor region” unless the St. Andrews board decided they were “no longer necessary and appropriate.”

“We were acutely aware of who we were dealing with and the relative power of each entity, so we were trying to protect St. Andrews from exactly the situation we are facing at this time,” says Boothbay Harbor attorney Tom Berry, who was on the board at the time. “We wanted to make sure they couldn’t just scoop up the endowment and move everything to Damariscotta.”

But in 2007, St. Andrews’ local board signed another agreement, this one to effectively merge with Miles Memorial in Damariscotta, creating Lincln County Health Care. While the hospitals retained their separate legal identities, for practical purposes St. Andrews lost its independence. LCHC, Miles and St. Andrews have since had boards with identical compositions, meet simultaneously and share the same minutes. A majority of board members are either from the Damariscotta area or are employees of LCHC, which has led some in the Boothbay area to charge that their community’s interests were underrepresented when the board, behind closed doors, decided to suspend general surgery, acute care and, ultimately, the emergency room.

“People in this community feel this big corporate machine came in here and somehow underhandedly ended up with the gift Dr. Gregory gave this town,” says Good. “They’ve taken equipment out of here, dismantled the place and stripped it.”

ER NO LONGER SAFE?

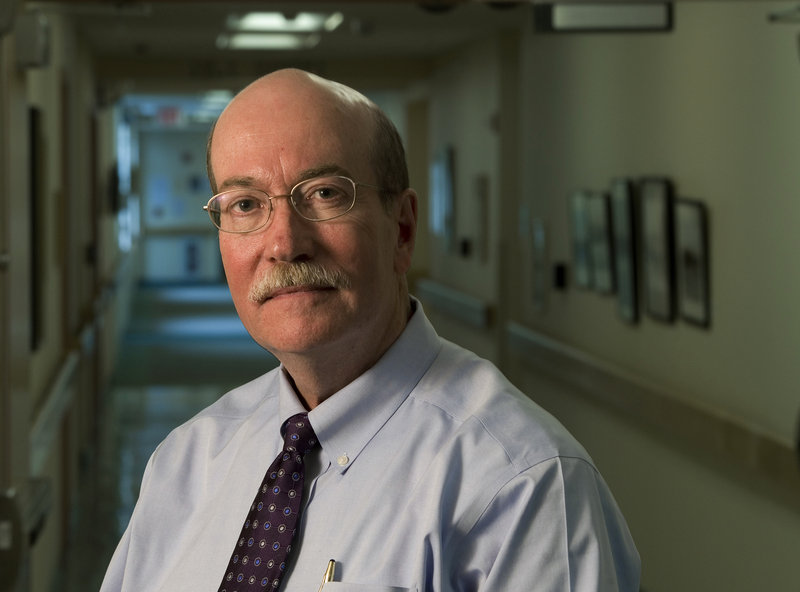

Nothing could be further from the truth, says emergency room physician Mark Fourre, LCHC’s chief medical officer and a board member, who formerly headed the St. Andrews emergency department. The changes, wrenching though they may be, are both desirable and vitally necessary, he says.

Over the past six years, Fourre notes, emergency room visits to St. Andrews have fallen by 20 percent. “When you get down to that kind of volume, you end up with a skeletal crew, with a single nurse and a single physician,” he says. “If you get somebody who is critically injured or ill, they need a team to care for them, and at St. Andrews we can’t assemble that team. But 20 minutes away (at Miles) there’s an ER with physicians and a pediatrician and surgeons.”

“In my opinion,” he adds, “arriving at an ER that doesn’t have the people or supplies they need to effectively run a resuscitation on a critically ill person or individual — that’s more of a risk than 15 extra minutes in an ambulance.”

That quality of care concern weighed most heavily in the board’s decision last year to close the emergency room, says board vice chairman Jeff Curtis of Boothbay Harbor, owner of Sherman’s Books and Stationery stores.

“If it were just a matter of money, we would be carrying on and finding ways to raise money to close the gap, but it wasn’t,” he says. “Once you get down to one doctor and one nurse, you’re counting on there not being a serious emergency. The ambulances are coming for you if you’re open, but you’re counting on there not being any three-car accidents.”

“We’re a volunteer board, and when the ER docs are coming in and saying, ‘We don’t feel safe in the middle of the night,’ you have to take that seriously, and we did,” he said, adding that there was no pressure on the board from MaineHealth, which touts its track record of not interfering in local board decisions.

CHANGING FACE OF HEALTH CARE

MaineHealth administrators stress that St. Andrews isn’t closing — they hate the term — even if it is losing its hospital designation, beds and emergency department.

The hospital’s waterfront campus on the west side of Boothbay Harbor will continue to house a lab, X-ray, and physical, occupational and speech therapy services, Fourre says. On Oct. 1, the emergency room will convert into an urgent care center that can treat the roughly 80 percent of the patients who currently visit the ER during daytime hours but don’t turn out to have truly emergency conditions. It will be open 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., and to 8 p.m. in the summer months, when the region’s population jumps from 7,000 to between 20,000 and 50,000.

They point to the low demand for emergency services at St. Andrews, which now sees an average of 12 patients a day, most of whom arrive during daytime and early evening and only 17 percent of whom turn out to require emergency care. This means the vast majority of demand will be met by the physician-staffed urgent care center but at a fraction of the cost of maintaining the emergency department

MaineHealth will also reduce capacity at Miles, where ambulances from the Boothbay region will be diverted this fall. The number of inpatient beds will be reduced from 38 to 25, and the hospital will maintain an average inpatient length of stay of four days or less.

This means Lincoln County as a whole will see a reduction from 63 to 25 hospital beds, but MaineHealth administrators say there will be enough capacity most of the time. (Miles currently has an average daily census of 19 inpatients — most requiring acute-level care — while St. Andrews has nine, all of whom are so-called “swing” patients requiring a lower level of care.) On days when the scaled-down Miles can’t meet demand, ambulances would likely be diverted to Brunswick’s Mid Coast Hospital, Pen Bay Medical Center in Rockport, or Maine Medical Center in Portland.

The changes are necessary in order for Miles to inherit St. Andrews’ status as a Critical Access Hospital under the federal Medicare program. This designation — which supports rural hospitals — will bring Miles an additional $5 million to $6 million in annual Medicare reimbursement payments, says MaineHealth CEO William Caron, who says it is vitally important to the long-term prospects of Miles.

“Before getting the critical access designation, I’ve got to tell you that hospital services in Lincoln County were under tremendous pressure,” Caron says, largely the result of serving a small, increasingly elderly population base. With a large proportion of the year-round population on Medicare — which pays hospitals less than private insurers do — Caron says Miles and St. Andrews have had to shift more of the cost burden to privately insured clients, resulting in high prices for their insurers. “Insurers were saying, ‘Your unit cost of care is excessive,’ and were starting to carve us out of their networks.”

For private insurers, Miles is by far the most expensive of Maine’s 24 smaller hospitals, according to a January study prepared for the state Office of Employee Health & Benefits, with 2011 pricing more than 27 percent higher than the statewide average. St. Andrews was the next most expensive at 17 percent above average.

“We have been struggling to sort out how to keep the greatest level of service we can in Lincoln County, so that people don’t have to come to Portland or Mid Coast,” Caron explains. “St. Andrews’ emergency room is not the last point of discussion we’re going to have there. We have other services that are being challenged.”

The critical-access designation — which requires Miles not have more than 25 beds — has given that hospital breathing room. “This critical access thing took a lot of the pressure off, and I can’t sit here now and tell you how long that’s going to sustain it, but it’s going to sustain it for a while,” Caron says.

THE AMBULANCE ARGUMENT

But the new arrangement will increase pressure on an entity that is not part of MaineHealth: the nonprofit Boothbay Region Ambulance Service, whose operations are subsidized by the region’s taxpayers.

Instead of a short drive to St. Andrews, ambulances will need to get patients to Miles, a 30-minute drive from downtown Boothbay Harbor, 40 minutes from the southern tip of Southport or Ocean Point in Boothbay. There is only one proper road off the peninsula — Route 27 — which is subject to summertime traffic congestion and winter weather.

Emergency patients are typically brought to St. Andrews, stabilized and then transferred to Miles or a larger hospital for further treatment. LCHC argues they are better served by being stabilized by the ambulance crew while en route to a fully staffed hospital.

“You will be stabilized in the back of that ambulance — they have the capability to do that,” says Donovan, who notes LCHC is helping the ambulance service install iPads so doctors can talk face to face with paramedics and patients. “Ambulances these days are really four-wheeled intensive care units.”

The operations director of the ambulance service, Scott Lash, isn’t so sure. “We’re talking about a fully functioning emergency department shutting down, and they’re turning around and saying, ‘Just look at the ambulance; they’ll bridge the gap,”‘ Lash says. “That’s a huge expectation.”

Lash is also concerned that his service will be stretched thin, both in terms of resources and in reaching people quickly when they call 911. At present, Lash says, his crews can respond to a call, deliver someone to St. Andrews and be available for another call in as little as 30 to 40 minutes. This allows them to cover the peninsula, even in summer, with their fleet of three active ambulances, although it’s not uncommon to have all three on the road simultaneously.

But Lash expects that “turnaround time” will jump to between an hour and 1:50 to get people to Miles, even without traffic or weather complications. The result? “We’ll be throwing caution to the wind,” he says. “If you’re one of the first to call 911, you’re in luck. If you’re not, you may be waiting for an ambulance to come from Wiscasset or Damariscotta.”

The ambulance service’s expenses will also go up, both because crews will be out longer and traveling farther, and because they will be making fewer billable trips transferring stabilized patients on from St. Andrews to a larger hospital. The service estimates local taxpayers will have to increase the subsidy they pay from just over $80,000 to more than $400,000 annually. LCHC has pledged a one-year gift of $250,000 to the towns to help defray the costs.

A STEP BACKWARD?

Many on the Boothbay peninsula believe the changes are a step backward. Among them is physician Nancy Oliphant, who maintains the only independent practice on the peninsula and had full hospital privileges until its acute beds were taken away in 2010.

“Nobody ever said St. Andrews can do it all, but they can do just about as much as Miles can, and the community here grew up around it and depends on it,” Oliphant says of the hospital, which is the only one in the state with both a helipad and a dock, which receives patients from the islands or Coast Guard rescue. “They can stabilize you and get you off to someone who can get you proper care, or keep you overnight when the roads are too ugly.”

She also believes LCHC programmed the hospital for failure.

“By taking away the acute care beds, they doomed the surgery department, because if there were complications in surgery, surgeons want to have somewhere on site that is appropriate to park the patient,” Oliphant says. “Then they cleaned out the operating room last April ‘temporarily’ and stripped it of its equipment, even though it had been renovated just a few years earlier.”

Donovan says the surgery was closed because it was being used for only about seven “minor cases” a week, and the equipment was moved to Miles. The fair market value of the equipment was transferred between hospitals, he says, so “essentially, Miles purchased the used equipment from St. Andrews.”

Boothbay Harbor resident George McEvoy played a key role in the operating room’s renovation, as he serves on the board of a foundation named for his mother that gave $100,000 between 2001 and 2006. He also thinks LCHC didn’t want the hospital to succeed, in part because he says it didn’t reapply for additional funding after the original five-year award played out.

McEvoy recalls a recent visit to the St. Andrews ER in the middle of a nighttime blizzard. He experienced a complication while recovering from surgery performed at Pen Bay in Rockport. The Pen Bay doctor on call said he needed to go to an ER but that the roads were impassable.

“He said he lived 20 minutes from the hospital, but the weather was so bad it had taken him two and a half hours to get there,” McEvoy recalls. “But he asked how far I was from St. Andrews and said there’s nothing they can’t do there that he could do.” McEvoy’s four-wheel drive got him there in a few minutes, and a crisis was averted.

McEvoy agrees St. Andrews’ ER is limited, but “it’s a lot better than sitting in an ambulance stuck in a snowdrift.”

‘BEST CARE IN THE STATE’

Opponents of the changes say LCHC and MaineHealth should have found a way to keep the ER open and properly staffed, and could have looked to the community to help bridge the financial gap.

“I really wish they would look at ways of making the hospital viable rather than ways of cutting their expenses,” says Southport Selectman Stuart Smith, a software and business process consultant. “There are ways to make both those hospitals economically viable year in and year out.”

St. Andrews actually turned a $182,000 profit last fiscal year and $874,000 in fiscal year 2011 but has an overall loss of about $2 million over the past 13 years.

Many here say they no longer trust the hospital networks and now want management of the hospital returned to the community, although it’s not clear how that would be accomplished.

Patricia Seybold, president of the Boothbay Region Health & Wellness Foundation, a newly formed nonprofit, says her organization “will do everything in its power to retain 24-hour emergency services for the people on the Boothbay peninsula.”

“We’re not done yet, and we’re going to keep fighting until they close the doors of the emergency room,” she says, but declines to be more specific. “We’re not in a position to divulge our legal strategy at this point.”

But MaineHealth officials believe there are no further obstacles to going ahead with the changes. The result, they insist, will be better care for the region’s residents, as resources are shifted to local primary care and outpatient services.

“We are changing the way care is being provided on the peninsula, and it’s going to be the best care in the state of Maine when we’re done,” Caron says. “The problem is that we’re taking away a service and we haven’t had a chance to prove to them yet.”

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Twitter: @WoodardColin

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story