PORTLAND – Togue Brawn is on a mission — a mission to get you to eat more fresh Maine sea scallops.

Sea scallops are so delicious, Brawn and other scallop experts say, that fishermen always claim they are best eaten raw, right on the boat.

“When you have a really, really fresh scallop, it has an ocean flavor,” Brawn said. “When it’s raw, it has a really good texture, and it doesn’t have a fishy flavor at all. Scallops in general, relative to other seafood, are mild, but Maine scallops particularly are very mild. It’s almost a shame to cook them because they’re so good raw.”

Or cooked in butter with a quick pan sear, just enough to caramelize the surface and barely cook the center through.

Brawn is a former resource management coordinator for the Maine Department of Marine Resources who believes in the product so much she became a scallop dealer. As owner of Maine Dayboat Scallops Inc., she buys sea scallops from local fishermen and sells them to Rosemont Market and restaurants such as Miyake, Yosaku, The Grill Room, The Corner Room and The Front Room.

The Maine scallop season is short — it started in early December and will end in early March — so consumers should take advantage of it while they can, happy in the knowledge that every time they serve the shellfish this winter, they will be helping out a struggling fishery and Maine fishing families.

The scallop fishery in the Gulf of Maine tends to go through booms and busts, and it is currently recovering from a big bust.

“It boomed in the ’90s and a lot of people got into it, and it got overfished,” Brawn said. “The fishery collapsed, and it stayed low for a long time.”

Scallops are found all along Maine’s coast, but at least three-quarters of the state’s harvest comes from Washington and Hancock counties. The Maine grounds were closed for three years while fishermen and managers worked together to come up with a plan to build it into a more sustainable fishery. This winter, the closed areas have opened again for the first time, but with limited access and rotation schedules similar to crop rotation on a farm.

The New England scallop fishery in general is doing well. After federal fishing grounds offshore were closed down to protect groundfish, scallops rebounded quickly — so quickly that sea scallop landings in New Bedford, Mass., recently reached $450 million, according to Karin Tammi, a Rhode Island marine biologist whose students call her “The Scallop Queen.”

Brawn thinks if Maine scallops are managed well, they could eventually could bring in tens of millions of dollars to the economies of the state’s coastal communities. “There’s a lot of room, I think, to really brand Maine scallops because we do have something different,” she said.

Maine scallops are so fresh you can flick them and they move, nerves still firing. While scallops caught in federal waters are often on the boat for 10 days, Maine dayboat scallops are landed the same day they are caught and can be on the plate within a day or two.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s caught by a diver or a dragger,” Brawn said. “If it’s caught by a Maine fisherman, it’s a dayboat product and it’s going to be superior to something from the federal fishery.”

Tammi thinks that New England scallops, no matter where or how they were harvested, could become the next premium seafood product shipped to Asia and other markets around the world.

“I think our New England product is so good,” she said, “whether it’s the bay scallop or sea scallop, we should really be embracing this as a prime product, like a lobster.”

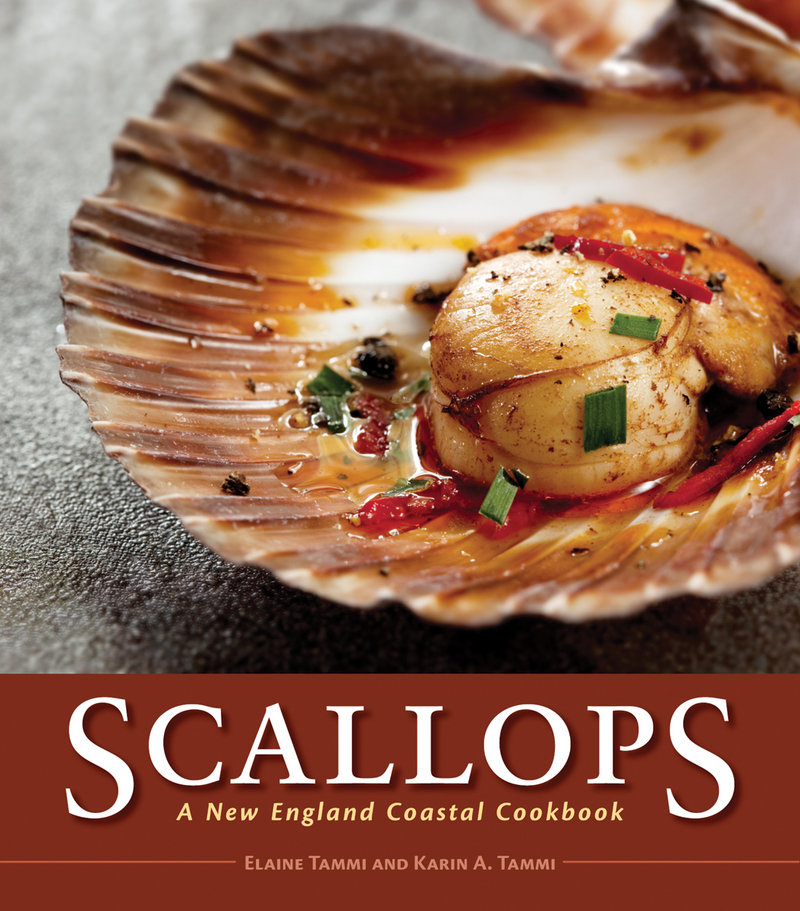

Tammi and her mother, Elaine Tammi, published a cookbook last year focused on the scallop. “Scallops: A New England Coastal Cookbook” (Pelican, $39.95) includes the history of the New England scallop industry, a primer on the biology of the scallop and dozens of recipes, including 22 from professional chefs.

The women were encouraged to write the book by the late Julia Child, who told them her favorite seafood was the scallop. (They still have a collection of letters from her advising them on how to get published.)

The Tammis and Togue Brawn have lots of tips for consumers regarding how to purchase and cook scallops at home and order them in restaurants.

BUYING SCALLOPS

Know where to go. Karen Tammi says it does make a difference where you go to purchase your scallops — a local seafood market or a grocery store chain.

“Some of the large supermarket chains, they try to do a good job with getting the freshest product, but sometimes they’re not the diver scallops, they’re not the dayboat scallops,” she said. “They’ve been frozen and processed and thawed out from large blocks of scallops, maybe 5-pound blocks. So when you go up to the seafood area, you’ll look in the case and see these scallops sitting in water.”

Know the difference between wet scallops and dry scallops. Before scallops hit the display counter, sometimes they’ve been soaked in either water or a chemical food additive called sodium tripolyphosphate (STP). If they’re sitting in a pool of milky water, chances are they’ve been processed with STP to increase their weight and extend their shelf life by seven to nine days so they can travel to stores across the country.

Soaked scallops don’t taste dramatically different, but the extra liquid will affect how they cook in the pan. It’s hard to get a nice sear on a wet scallop.

“You end up with a swollen scallop meat,” Tammi said. “You’re paying for that extra water weight. When that hits the hot pan or your casserole dish, heat releases that bond and the scallops will weep all that water out and make your dish very watery, and they actually poach in the liquid.”

STP, by the way, is also used in processing shrimp.

Sea scallops run $15.99 to $18.99 a pound in the New England region. Brawn charges chefs $16 a pound, and $17 to $18 a pound to consumers. Diver scallops can run $35 a pound. Why pay more for added water?

“If you live near the ocean,” Elaine Tammi said, “chances are you’re going to get the dry scallops in a good fish market.”

Don’t be freaked out by color. The tastiest scallops aren’t necessarily white. Consumers are used to seeing little white nuggets on their plates. But there’s a lot of natural variation in the color of scallops, so you may see some at the market that have a pinkish or orangish hue. Sometimes these scallops are much sweeter than the ones that are naturally white.

The color comes from a carotenoid the scallop needs to produce its roe and feed its larvae, Brawn explained. The females accumulate it when they’re filter feeding and store it in their adductor muscles — the part of the scallop we eat.

Scallops that are pure white may have been soaked, which takes color away. Or they may look that way for a not-so-palatable reason.

“There are a few processing companies that may actually bleach that color out of them, and it’s allowable to a certain extent,” Karen Tammi said. “But I found that to be disgusting when I heard it.”

COOKING SCALLOPS

Trim the foot. The part of the scallop we eat in the United States is the adductor muscle. (In Europe they eat the whole scallop.) There’s a little piece of meat that may still be attached to the adductor muscle after shucking that many people call the foot. It’s chewy and doesn’t taste like the rest of the scallop meat.

“A lot of chefs are leaving the foot on,” said Elaine Tammi. “It should be taken off. Some chefs like to make a sauce of just the feet because they do have a stronger taste than the scallop does.”

If you’re going to pan sear your scallops, choose dry scallops. Put a steel pan over medium-high heat. Add butter or some olive or grapeseed oil. Season the prepared scallops with salt and pepper and gently put them in the pan. A bay scallop will take about 45 seconds per side to sear, Karen Tammi says, while a sea scallop will take 1 to 1½ minutes per side.

Once you put the scallop in the pan, don’t move it around. Let it sit there so it can caramelize on the bottom. When the scallop is ready, it will pull away easily from the pan without sticking.

“You pull two or three of those off, go into your cabinet and find your favorite dressing, then get some nice greens and serve that as a salad or a light dinner,” Tammi said. “Put your own dressing on it, and it makes you look like you’re one of the best chefs ever. It’s a very easy recipe, and it’s quick too.”

There are lots of variations to a good pan sear. Elaine Tammi likes hers cooked in brown butter.

“You let the butter get very brown, and then as the scallops are in the pan you just spoon some of the brown butter over the top.”

Brawn’s favorite way to prepare scallops is to pan-sear them in butter and then top them with a dollop of Kewpie mayonnaise, a popular brand of Japanese mayo.

She also suggests a preparation that’s a favorite at J’s Oyster on the waterfront: Make a sauce that’s two parts butter and one part honey. Pan sear the scallops in butter, then add the honey-and-butter mixture and spoon over the shellfish. Put the scallops in a casserole dish, sprinkle with cracker crumbs and broil them.

Try them many different ways. Scallops are versatile. You can bake them, broil them, sear them, saute them, grill them or use them in a ceviche.

Don’t overcook. This will just make the scallop meat tough. Better to undercook than overcook.

ORDERING SCALLOPS IN A MAINE RESTAURANT

Ask questions. If it’s not December, January, February or March, it’s not scallop season, and chances are the “fresh Maine dayboat scallops” you see on the menu are either not from Maine or they have been frozen.

Chefs aren’t necessarily lying about what’s on their plates; they may have been told they were buying Maine scallops when they were not. The key is to ask questions, Brawn said, so that chefs, dealers and market owners will know that having fresh Maine product is important to consumers.

“(Consumers) want small boats, not corporate boats,” Brawn said. “They want really fresh seafood, not older seafood. They want it not treated. So Maine really has an opportunity. There’s a lot of economic potential in Maine’s scallop fishery, and it’s not going to be realized until consumers start demanding Maine scallops.”

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story