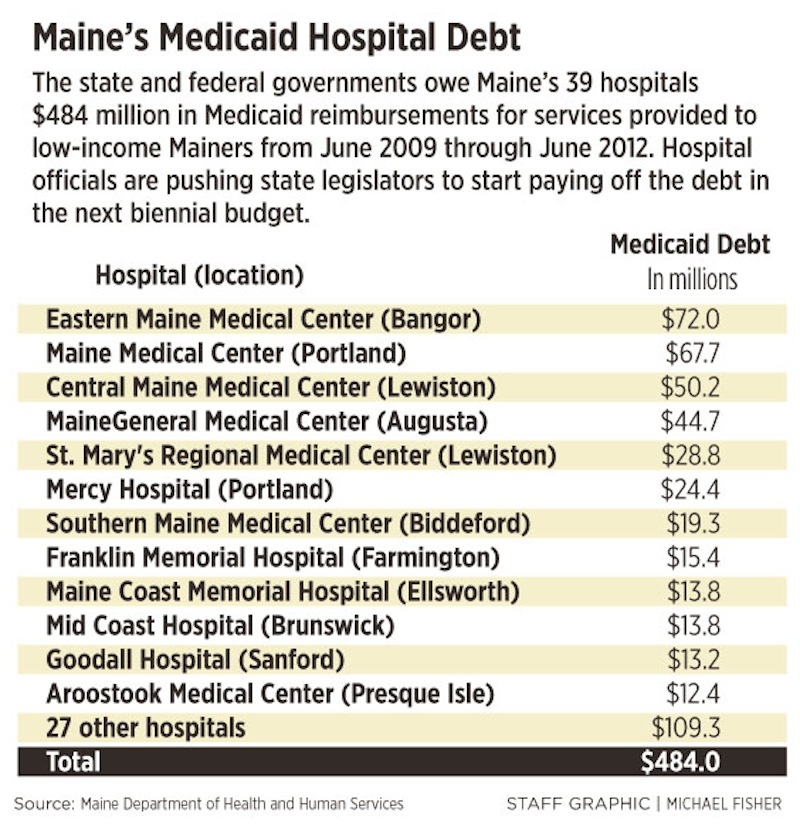

Owed $484 million in overdue Medicaid reimbursements, Maine’s 39 hospitals are pushing state lawmakers to find a way to start paying off a debt that’s forcing some hospitals to reduce staffing, delay capital improvements and borrow money to pay bills.

The state’s share of the debt is $186 million. Some of it dates back to 2009, and it must be paid to free up about $298 million in federal matching funds that some hospital officials say they need desperately.

Their lobbying effort — advertisements in newspapers and meetings with lawmakers — comes as the Legislature prepares to deal with a projected $120 million revenue shortfall in Maine’s current budget for MaineCare, the state’s version of Medicaid.

The reimbursement debt affects hospitals large and small across the state, from Maine Medical Center in Portland ($67.7 million), to Central Maine Medical Center in Lewiston ($50.2 million), to Aroostook Medical Center in Presque Isle ($12.4 million).

Central Maine Medical Center is leaving jobs unfilled, including a vice president’s position, and delaying all but emergency capital spending, including long-planned building projects for obstetrical and primary care services.

“This can’t continue,” said Chuck Gill, the hospital’s spokesman. “When you have a bill, you have to pay it. We provided care two or three years ago, in some cases, and we’re still waiting for payment.”

A few blocks away at St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center in Lewiston, officials announced this month that they plan to restructure and eliminate as many as 25 positions if they don’t get their Medicaid reimbursements, which now total $28.8 million.

Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor, the state’s top Medicaid creditor, is waiting for $72 million in reimbursements. In the last fiscal year, the seven hospitals in the Eastern Maine Healthcare Systems lost a total of $4 million in interest they would have earned on savings used to cover operating expenses, said Lisa Harvey-McPherson, vice president of continuum of care.

“That money is lost,” she said. “That could have gone into patient care and services. It puts all hospitals in Maine in a challenging cash-flow position.”

The current reimbursement debt accumulated from June 2009 through June 2012. During that period, the Maine Department of Health and Human Services had a unique practice of paying estimated weekly amounts for hospital services and leaving millions in reimbursements unpaid each year.

The debt grew as eligibility expanded for MaineCare, which covers low-income families and individuals. In the mid-2000s, the number of Mainers receiving Medicaid benefits grew from about 200,000 to 300,000, said Jeff Austin, spokesman for the Maine Hospital Association.

“The result was a total reimbursement gap of $80 million to $120 million per year,” Austin said. “It’s a pain to carry forward that kind of receivable. The last meaningful payment (the state issued to hospitals) was $70 million two years ago. The age of this debt is getting people antsy.”

The Legislature moved the state to a pay-as-you-go policy in July, ensuring that the DHHS would start paying its Medicaid bills on time. The transition had been in the works for a while, said Austin, who credits Republican Gov. Paul LePage and a Republican-led Legislature for making it happen.

Now, with Democrats back in the majority, the Legislature prepares to return in January with a $120 million shortfall in the current MaineCare budget, which the LePage administration has attributed largely to technical miscalculations.

“Certainly the state needs to pay its bills and we are sensitive to the financial challenges facing the hospitals,” said Senate President Justin Alfond, D-Portland, in a prepared statement. “It’s important that we plan with the hospitals how we are going to pay for the work they’ve done and continue to do.’

Rep. Peggy Rotundo, D-Lewiston, has served for the last eight years on the Legislature’s Appropriations Committee.

“We know we need to pay this debt,” she said. “We’ve been working hard over the last few years to pay it down.”

Hospital officials have suggested tapping the state’s lucrative liquor distribution contract, which is set to expire in 2014. Lawmakers hope to negotiate a better deal than the current 10-year exclusive agreement, which gave the state $120 million up front and $40 million in revenue sharing.

Senate Minority Leader Mike Thibodeau, R-Winterport, said that whatever the Legislature does may be compounded by federal spending cuts that have been proposed to combat the so-called fiscal cliff.

“We want to be mindful of the fiscal situation in D.C.,” Thibodeau said. “Our hospitals have rendered services in good faith that the state of Maine would pay them. It’s unconscionable not to pay people the money we owe them.”

The federal share of Medicaid reimbursements spiked to nearly 75 percent in fiscal 2009-10 as a result of President Obama’s economic recovery funding. It has fallen back to 63 percent for fiscal 2012-13 and is expected to drop to 62 percent for 2013-14, said Adrienne Bennett, the governor’s spokeswoman.

“The hospitals are right,” LePage said in a prepared statement. “The state needs to pay up. The health care industry is depending on that money and the longer Maine waits to pay its bills, the more our economy struggles.”

LePage noted that hospitals, taken as a whole, are Maine’s largest employer and could be a source of economic growth.

Hospitals provide jobs for nearly 30,000 people, but several have eliminated a total of nearly 200 positions in recent years through attrition, buyouts and layoffs, according to the Maine Hospital Association.

“Health care careers that Mainers need and are qualified for are not being filled,” LePage said. “It’s time we make good on what’s owed so we can kick-start our economy.”

At Maine Medical Center, the state’s second-biggest Medicaid creditor, the situation is less dire than at other Maine hospitals, said Al Swallow, vice president of finance.

That’s because Maine Med has a larger proportion of patients with private health insurance and is less dependent on Medicaid, Swallow said. However, if the $67.7 million debt remains unpaid, it could hurt Maine Med’s bond rating and increase interest rates on future borrowing.

“It’s still not good,” Swallow said. “It’s money that’s owed to us.”

Swallow said he’s concerned about how the Legislature might pay the Medicaid debt, given few public revenue sources.

“We would be worried if that payment came at the expense of a reduction in rates paid for services we provide in the future,” Swallow said. “(Legislators may) get to a point where they’re stuck between a rock and a hard place.”

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 4:30 p.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 19, 2012, to show that in the last fiscal year, the seven hospitals in the Eastern Maine Healthcare Systems lost a total of $4 million in interest they would have earned on savings used to cover operating expenses.

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story