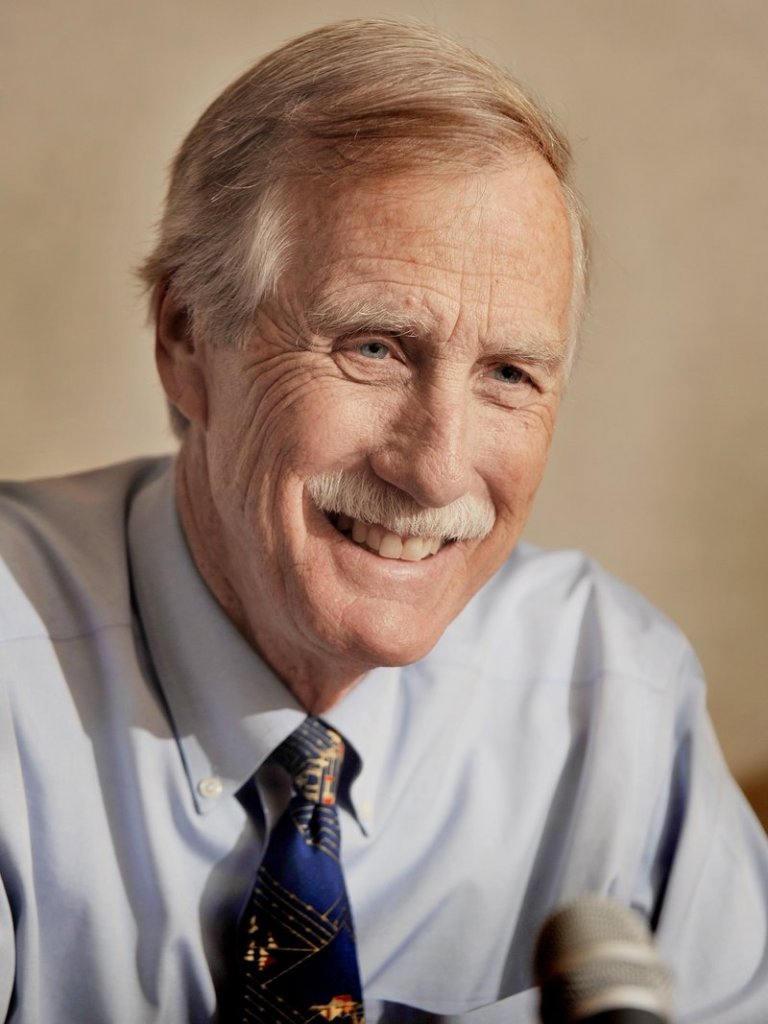

The email on Sept. 18 from an Angus King campaign staffer to the interns was marked urgent. “Take action!!” was stripped across the top in a bold font.

The problem? Unflattering comments posted below an online news story about King’s campaign for Maine’s open U.S. Senate seat.

“There are 11 comments as of 4 p.m., almost all negative,” wrote staffer Adam Lachman. “Can you please take time to comment on this article and help correct the record?”

Over the next hour, King’s interns and volunteers, most using screen name aliases, peppered the Bangor Daily News story with comments that echoed talking points suggested by Lachman.

One commenter, “Mysteriousways7,” posted Lachman’s suggestions nearly verbatim, then added a second post with a link to “Standing Up for Truth,” a King video suggested by Lachman.

The email and several others obtained by Crash Barry, a freelance writer who is a vocal critic of King and his Senate candidacy, show how the campaign deployed volunteers to comment, often anonymously, on online news stories to counter attacks and amplify support for King.

Although King may be criticized for the practice, he’s not the only one using it. Political operatives say online comments, blogs and other forums have become part of modern campaigns, which use any platform available to inflate support, project messages and counter opponents.

“As long as there have been chances for political campaigns to get a free shot at getting their message out, they’ve done it,” said Dan Demeritt, a political consultant who has worked on several campaigns, including Gov. Paul LePage’s in 2010. “This happens all the time, absolutely.”

Crystal Canney, King’s spokeswoman, said the campaign is doing the same thing as its opponents.

“They all do it,” Canney said. “I dare say that when you see a group of negative comments, or a group of positive comments, that those comments are affiliated with a campaign in some way.”

Not surprisingly, King’s opponents note that the former governor has portrayed himself as a different kind of politician.

“This is in keeping with the disingenuous campaign that he’s run,” said Lance Dutson, campaign manager for Republican U.S. Senate candidate Charlie Summers. “He makes these pledges about negative ads and out-of-state money and he ends up running the same old campaign that anybody else would run.”

He said, “It doesn’t surprise me at all that the enthusiasm that might appear online is bought and paid for as opposed to actual grass-roots enthusiasm.”

Dutson said the Summers campaign hasn’t used similar tactics, but has told its county chairmen that “engaging in the online discussion is a way to help.”

He said he has seen organized efforts by other campaigns to use online comments, “but we’re not giving marching orders for folks to comment on specific articles.”

A spokeswoman for Cynthia Dill, the Democratic candidate for Senate, said the campaign does not engage in the practice.

Dennis Bailey, a political operative who was communications director for King when he was governor, said campaigns aren’t being honest if they deny using anonymous reader comments to create a false sense of public opinion.

Bailey said operatives and volunteers sometimes use multiple aliases to create “an echo chamber.”

Demeritt compared online commenting to the more time-honored practice of enlisting people to submit letters to the editor.

“Campaign supporters will actually draft up talking points and write letters for people to sign,” Demeritt said. “It’s a prevalent practice.”

Bailey said campaigns also use online comments to plant rumors or opposition research. News organizations may try to separate their news product from the comments, he said, but the public often doesn’t make the distinction.

Bailey blames the false reality on anonymity. His comments may seem hypocritical, given his involvement in 2010 in the Cutler Files, an anonymous website attacking gubernatorial candidate Eliot Cutler.

Bailey was fined $200 by the state ethics commission for his lack of disclosure about the website. He later sued the state, arguing that the Cutler Files was journalism. A judged ruled against him.

Bailey acknowledges his contradicting opinions.

“My joke at the time was that I should have just posted Cutler Files on the readers’ comments piece by piece, and that would have been legal,” he said.

News organizations have struggled to deal with anonymity, which some believe has lowered the level of discourse in online comments. In 2010, the Lewiston Sun Journal began requiring commenters to use their real names to post comments on the paper’s website.

The Portland Press Herald, the Kennebec Journal and the Morning Sentinel switched Monday to a system that requires commenters to use Facebook accounts. The Press Herald previously allowed commenters to post anonymously. The Bangor Daily News still does.

Canney, with the King campaign, said that engaging in online comments isn’t a focus of the campaign.

“We do think it’s an important part of the campaign,” she said. “Do we think it’s the biggest part, or the most significant? Absolutely not.”

Canney would not say how the emails showing the campaign’s commenting practice were leaked.

Barry, who shared the emails with the Press Herald, also was reluctant to provide details.

“I’ve had multiple, disillusioned sources within the King camp furnish me with various passwords, codes and tips since June that allowed me occasional access to the inner workings of the campaign,” he said.

Staff Writer Steve Mistler can be contacted at 791-6345 or at:

smistler@mainetoday.com

twitter/stevemistler

This story has been updated to note the date that the Sun Journal changed its online commenting policy.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story