Carol Paulson thought she was doing the right thing when she called 911 and asked Kennebunk police to come and get her daughter.

Thirty-nine-year-old Katherine Paulson, who was mentally ill and had stopped taking her medications, could be violent at times. Her mother told the dispatcher that her daughter had psychological problems, and that she feared for her own safety.

In calling police, Paulson hoped to have her daughter involuntarily committed to a treatment center, where she would be medicated again and stabilized. But 19 seconds after police arrived at the Paulson condominium, Katherine Paulson was dying on the kitchen floor.

Officer Joshua Morneau, who was not told by the dispatcher about Paulson’s mental health problems, had shot her four times at close range. He later told investigators that he was cornered and felt threatened, after the woman came at him with a knife clutched in her right hand and refused his orders to drop it.

“I was looking for assistance,” Carol Paulson said. “I wasn’t looking for what I got, let’s put it that way – the end of her life and the end of my life as I know it.”

An investigation by the state Attorney General’s Office found that the shooting was legally justified. An independent review led by Kennebunk police concluded that department policies were clear and training was appropriate.

A cop. A gun. A disturbed or impaired person with a weapon of their own.

These elements can be the ingredients of tragedy, and when they are combined, that’s often the result.

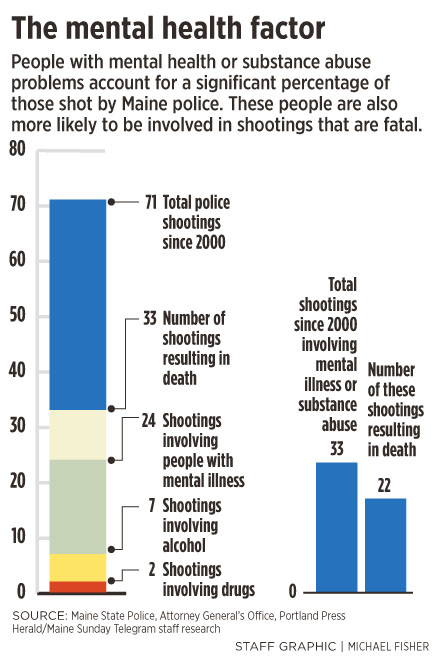

Since 2000, police in Maine have fired their guns at 71 people, hitting 57 of them. Thirty-three of those people died. A review of these 57 shootings by the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram found that at least 24 of them, or 42 percent, involved people with mental health problems. Seven of the shootings were alcohol-related. Two involved drugs.

Of the 33 people who were killed, at least 19, or 58 percent, had mental health problems.

Maine has one of the lowest violent crime rates in the country, and police shootings are relatively rare here. But the newspaper’s examination of these events shows that once police do draw their guns, a fatal outcome is likely. It also determined that while police may be aware that they are dealing with a mentally unstable person, they don’t always take adequate steps to avoid violence.

Among the newspaper’s findings:

• The vast majority of Maine’s 3,500 police officers lack the advanced training that can prevent or defuse the use of deadly force. Maine State Police, who are involved in more shootings than any other agency, have sent only 14 of their 200 patrol troopers to a training program offered in Maine and recognized nationally for its effectiveness.

• The Maine Legislature created a new system to review police shootings three years ago. But key lawmakers and police agencies haven’t taken the time to read the findings, even though 20 people have been shot since the reviews began.

• The Maine Attorney General’s Office, which investigates all police shootings, doesn’t ask whether violence could have been avoided. Instead, the reviews look only at whether an officer reasonably felt that he or someone else was threatened, and that deadly force was needed. The office has investigated 101 incidents since 1990, in which 51 people have died. Every shooting was found to be justified.

• Confidentiality protections for law enforcement personnel and a lack of data make it all but impossible for the public to evaluate police shootings in Maine. There’s no way to assess how Maine compares with other states, whether any shootings could have been avoided, or to what extent officers have been disciplined for shooting someone unnecessarily.

Against this backdrop, police in Maine shot nine people in 2011. Another six have been shot so far this year.

The 2011 shootings, which tied a record set in 2008, included five people who had mental health problems or were suffering a psychotic crisis, and one person who was drunk. All six people were killed.

Of the six shootings this year, three involved people with mental health or alcohol problems. One – an armed confrontation in June between U.S. Border Patrol agents and an intoxicated man in Jackman – ended with the man’s death.

In another, an Edinburg man who made homicidal and suicidal threats on the phone to state police was shot and wounded by a trooper when the man came at him with a knife. In the third case, a Hermon man shot himself to death after he was hit in the leg by state police during an exchange of gunfire in July.

Although shootings make headlines, police say the public doesn’t appreciate the many times they’re able to resolve volatile confrontations without using their guns.

Some incidents this year have drawn media coverage, though. For instance: Portland police used tear gas in May to end a standoff, after a man shot a woman with what turned out to be a pellet gun. Police in Mechanic Falls used a Taser in June to disarm an intoxicated man who threatened to kill a woman. In July, state troopers helped Winslow police end a standoff in which a man with a mental disorder threatened officers.

But violent encounters with disturbed people are likely to increase in Maine, police and mental health experts say. Ongoing cutbacks in social and psychiatric services, the return of veterans troubled by the experience of war, and the escalating abuse of prescription drugs are contributing to situations that put police in the role of front-line mental health workers. This trend is being observed nationwide, and in other countries.

“It’s really a mental-health services problem,” said Rosanna Esposito, deputy director of The Treatment Advocacy Center in Arlington, Va. “The reason police are involved is they’re the last resort.”

As more police find themselves in daily confrontations with mentally disturbed people, chiefs are putting their officers through a special Crisis Intervention Training program. But the effort takes time and money, and its value is hard to quantify. In Maine, the department that has been involved in the most shootings – the state police – has had very little of this training.

A recognition of these trends led the newspaper to look closely at issues raised by police shootings, including state and local policies on deadly force, police officer training and how cases are investigated. At the root of the examination were two questions: Could some of the violence and death have been avoided? Can steps be taken to help prevent future tragedies?

The newspaper found that Maine’s current system of investigating police shootings largely fails to answer these important questions. These shortcomings contribute to a perception that Maine police aren’t fully accountable when they pull the trigger, despite the sometimes life-and-death nature of their actions.

DISAGREEMENT ON POLICE METHODS

The findings also form a backdrop for disagreement between advocates – who want to see more alternative responses to deadly force – and police officials who say that, overall, their actions are responsible and prudent.

“I want the whole ethos and training to be altered,” said Orlando Delogu, a University of Maine School of Law professor emeritus. “The gun gets pulled too quickly, that’s my view.”

Delogu helped draft a bill three years ago that would have created independent citizen-review panels to look into deadly force shootings. That effort failed, but Delogu remains a vocal critic of current practices. He maintains that police could often back away from situations rather than shoot, or use less-lethal techniques, such as mace and Tasers.

As an example, he cites a case in November 2011, in which a Maine game warden shot and killed Eric Richard, a despondent, armed, Rumford police officer, after a search in woods near his home. The attorney general found the shooting was justified, but Delogu said he thinks the incident could have been resolved peacefully, with patience.

“Here’s a guy who is clearly disturbed,” Delogu said. “Did we need to chase him into the woods? You can pick him up the next day.”

But to York County Sheriff Maurice Ouellette, outside observers who judge police shootings with incomplete information are “Monday morning quarterbacking.” Although there are no national statistics to compare officer-involved shootings state by state, Ouellette said his contacts with police elsewhere convince him that Maine officers are well-trained and very conservative about using physical force.

“I think officers in this state go the extra mile to avoid that,” he said.

Ouellette had to confront the complex nature of police shootings last year, when one of his deputies killed a psychotic man in the York County town of Lyman.

The man, Andrew Landry, told family members about forces “in my head and coming through anything electrical.” He asked if his cousin would bleed if he stabbed her, because she was a robot. Worried for the family’s safety and unable to convince Landry to seek treatment, his grandmother finally called the sheriff’s office and told them what was happening.

Two sergeants arrived after dark at a mobile home and went inside, fearing that Landry would harm his cousin. Landry charged at one of them with kitchen knives. When his partner’s Taser failed to stop the advance, the deputy fired four shots from his handgun, killing Landry, who was 22 years old.

The attorney general’s investigation found the shooting was justified. A review team picked by Ouellette, made up largely of police, reached the same conclusion.

Neither of the York County sergeants had Crisis Intervention Team training, a program that teaches officers skills for dealing with people who are in a mental health crisis. The review team concluded, however, that the training wouldn’t have mattered, due to the speed with which the situation escalated.

Waiting out the suspect wasn’t an option, either, Ouellette said. One family member had left the building, but another remained inside and at risk.

“In my experience, I don’t see any other way this could have been done,” said Ouellette, who has had a 39-year law enforcement career in Maine. “I could have had everyone with CIT training and it wouldn’t have made a difference.”

But CIT training is important, Ouellette said, noting that 13 of his 21 patrol officers have gone through the program, and more are expected to attend a training session next year in Sanford.

DEALING WITH MENTALLY ILL FACTOR

When a disturbed person is shot by police, it’s really a failure of the state’s mental health system, said Carol Carothers, executive director of Maine’s affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“The real issue is prevention, before it gets to a point where police are there with weapons,” she said.

Maine has 170 law enforcement agencies, 134 of which have at least one full-time officer. All police academy graduates take a basic, seven-hour course to help them identify mental illness indicators and defuse crisis situations. Since 2009, working officers have gotten two hours of training in assessing use-of-force situations.

Relatively few, however, participate in Crisis Intervention Team training. Roughly 40 percent of Maine police officers are part-time reserve officers, who may have only minimal training. Many rural communities rely on these officers.

Carothers’ staff organizes and helps teach the CIT program. She would like more police to attend, but understands the financial pressures on police departments. She also is reluctant to comment on whether more training could have prevented some shootings.

“I never want to second-guess cops,” she said. “Cops run in when people run out, and they’re trained to keep people from hurting themselves. They are the people who step up in our society.”

LAWS SET JUSTIFICATION STANDARDS

Current policies and legal practices on deadly force in Maine stem from an incident in 1992. That’s when a state trooper and two county sheriff’s deputies stormed a remote cabin outside Jackman and killed Katherine Hegarty, a Maine Guide who had been threatening campers.

The officers were cleared of any wrongdoing by their superiors, but Hegarty’s death triggered national protests and an examination of how and when police use deadly force. It led the Legislature to pass a law – known as the Hegarty Law – that upgraded training at the Maine Criminal Justice Academy and set minimum standards for the use of deadly force.

A related law, enacted in 1995, required the state Attorney General’s Office to investigate whenever police shoot someone or use some other form of deadly force. The law also established the two-part “reasonable belief” standard for determining whether a shooting is justified. In Maine, all shootings investigated by the attorney general have been found to be justified under this standard.

Attorneys general in New Hampshire and Vermont cite similar “reasonable belief” language in their reviews of deadly force cases. The principle has been upheld nationally in test cases at the U.S. Supreme Court.

This doesn’t mean the officer’s judgment is always correct, said Terry Dwyer, a retired New York State Police officer and assistant professor at Western Connecticut State College. But courts and laws tend to err on the side of officer safety, he said.

“In general, it’s going to favor the officer – that’s the standard,” Dwyer said.

That standard also applies to internal disciplinary actions against officers who have shot people. As a result, public access to records of discipline are severely restricted.

The newspaper attempted to review disciplinary actions taken by the two departments involved in the largest share of shootings in Maine, state police and the Portland Police Department.

State police have been involved in 35 shootings since 1990. The newspaper sought any incidents involving disciplinary action back to that date. A state police data search turned up only one case, in 2000. It resulted in a five-day suspension, without pay, for a state trooper.

Under Maine law, all records of disciplinary action are deemed confidential, except for the final letter of discipline. In the 2000 case, the letter provided no details of the incident.

Using other sources, the newspaper learned that the case involved an incident in Ellsworth in which a trooper fired two shots at a 17-year-old boy who was holding a handgun to his head and threatening to commit suicide. The shots, according to a police statement at the time, were meant to knock the gun out of the boy’s hand, a practice that’s unauthorized and considered dangerous.

One shot grazed the boy’s shoulder, but he did not require medical treatment, police said.

More recently, a second disciplinary action has become public

It stems from a confrontation last year in Dover-Foxcroft, in which Trooper Jon Brown shot and killed Michael Curtis, who was drunk and had just shot a man outside a nursing home. The attorney general found Brown’s actions were legally justified. But state police determined Brown had violated department policies and suspended him without pay for 30 days last summer, transferring him from patrol duties and requiring him to complete “remedial training” in areas including use of force.

Portland police have shot 11 people since 1990. The newspaper sought any internal reports or complaints, but only five reports were available because the city’s labor contract requires that internal affairs records be purged after seven years.

In a 2008 case, an officer fatally shot a suspect who dragged him along with his car while trying to flee. The shooting was found to be justified, but the officer received a one-day suspension for not properly maintaining his cruiser’s mobile video recorder.

TOUGH, RARE SITUATION FOR POLICE

The standards governing police shootings, especially at the Attorney General’s Office, are not widely understood outside law enforcement circles. That can lead to public confusion and frustration, and a sense that police are unaccountable.

“There’s almost this theme that the police aren’t well-controlled,” said state Rep. Mark Dion, D-Portland. “But if you look at the sheer volume of physical arrests and traffic stops, deadly force is a tiny fraction.”

Dion is a former Portland police officer and Cumberland County sheriff. He chaired a state task force on mental illness and deadly force. And he used his law enforcement connections to take members of the Legislature’s Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee last year to the police academy, where they participated in use-of-force firearms training. Delogu, the law professor who is generally critical of police handling of deadly force incidents, also joined the trip.

Dion said one goal was to give lawmakers a first-hand experience, and to dispel the notion that police can intentionally wound suspects or shoot knives from their hands.

“The public thinks cops are Olympian sharpshooters,” he said. “There’s this idea that you can use deadly force in a non-deadly fashion.”

SUING THE POLICE OFTEN FUTILE

The courtroom provides a final forum for shooting victims or their survivors who feel police acted improperly. In Maine, it’s rare for those cases to succeed.

Individuals, or their estates, have the option to sue over the incidents in either federal or state court. The grounds could be violation of civil rights or the Maine Tort Claims Act, which is a more restricted definition.

The newspaper reviewed 22 cases between 2001 and 2011 in which police shot impaired or mentally ill people. Five of those cases resulted in civil lawsuits against officers and their agencies. None so far has resulted in a judgment against police.

Attorneys who represent police, municipalities, counties and the state in such cases are unaware of any settlements in police shootings in the past decade.

“By the time police in Maine shoot someone, it’s pretty clearly justified,” said Edward Benjamin, a Portland lawyer who specializes in defending municipal police officers. He said he has handled more than a dozen cases over the past 27 years and never had one go to trial.

Mark Dunlap, a lawyer who has represented Portland in excessive-force cases, said the Maine Tort Claims Act provides certain immunities to government employees on the job.

“Because of the general immunity police officers have by virtue of laws that have grown up around these types of things, a lot of (cases) are dismissed” with no settlement or trial, he said.

There are a couple of older, notable exceptions.

A wrongful-death federal lawsuit filed by Katherine Hegarty’s husband was settled in 1997 for $200,000. In 2000, the town of Brunswick reached an undisclosed financial settlement with the sister of Richard Weymouth. He was confined to a wheelchair but threatened a police officer, who shot him to death in a 1997 confrontation.

NOT A HOT ISSUE FOR LAWMAKERS

To Donald Pilon of Saco, a former state representative who went on the police academy visit organized by Dion last year, these rare exceptions argue for more oversight and accountability.

“Look at the number of shootings we have, and they’re all ruled legally justified,” he said.

Three years ago, Pilon co-sponsored a bill in the Legislature aimed at examining the training, policies and tactics that police used prior to a fatal shooting. It would have required police departments to form review panels dominated by non-police members such as clergy, a mental health professional and a lawyer. Delogu, the UMaine professor who is critical of police use of deadly force, helped draft the bill for Pilon.

But the measure was withdrawn after it ran into opposition from police agencies and failed to win support from the Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee.

Lawmakers instead passed a resolve measure that requires each police chief to set up an “incident review team.” These teams have one non-police member and focus on whether policies were understood and followed, and whether training and equipment were adequate.

Last winter, the board of trustees at the police academy sent a summary of the incident review team process to the committee. The summary listed the five shootings in 2010, and the nine in 2011.

But the summary did not include the actual results of any team’s reviews of individual shootings. The review teams’ findings are public records, but there’s no requirement to distribute them, or to sum up the findings for lawmakers.

In an interview earlier this year, Rep. Gary Plummer, R-Windham, said he was satisfied with the limited information. Plummer was the co-chairman of the criminal justice committee at the time the legislative resolve was passed. He said he hadn’t thought about reading the publicly available incident review team reports, but would do so.

Plummer also said he didn’t see a need to bring more people who are not police onto the review teams – beyond the one public member required by the resolve.

“I don’t see a problem with police evaluating police,” he said. “I don’t think they are protecting their own.”

There were no attempts in the last session of the Legislature to reconsider changes to the state’s deadly force law or policies. But it’s possible that the new Democratic majority will be open to revisiting at least one issue.

Rep. Anne Haskell, D-Portland, was the ranking Democrat on the criminal justice panel last year and hopes to serve on it again. In an interview last month, Haskell said the newspaper’s findings convinced her that reading the review team reports should be a priority on the committee. She said she planned to examine if they should be provided directly to lawmakers.

“At some point,” Haskell said, “there’s going to be a tragedy and someone’s going to raise this issue. We’re going to identify it as a missing link.”

Staff Writers Ann Kim and David Hench contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story