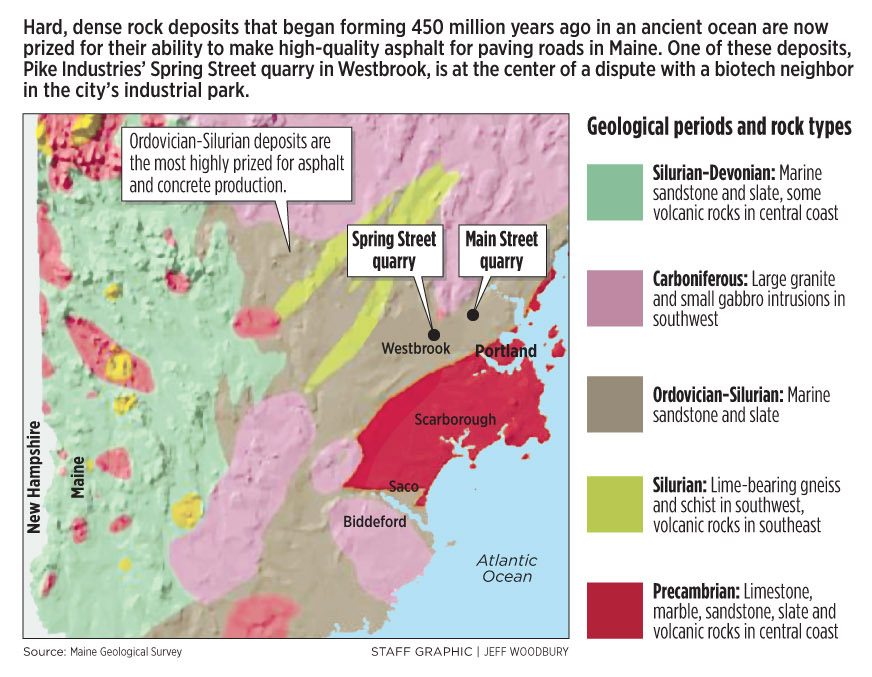

WESTBROOK – The high-stakes dispute over the quarry owned by Pike Industries and the proposed expansion of Idexx Laboratories has its roots in events that began 450 million years ago, when this part of the Earth was under an ocean.

In the eons that followed, heat and pressure formed a rock deposit that’s very hard and dense. The result: The rock in the Spring Street quarry is some of the highest-grade raw material in southern Maine for making hot mix asphalt, the road surface on which we drive. It exceeds the Maine Department of Transportation’s basic requirements for durability and weather resistance.

In another couple of geological coincidences, the deposit is close to most of Maine’s roads and people, and it’s not covered by thick layers of soil.

Those factors make the deposit particularly valuable to Pike, which is the primary paver of the Maine Turnpike and handles 75 percent of the paving in southern Maine, according to state estimates. They also help to explain why Pike is mounting such an aggressive legal and public-relations fight to reopen and expand its quarry.

Pike’s estimate, there’s enough rock in the quarry to last another 80 years, making it worth $600 million.

“The quality of the rock and its location is irreplaceable, as far as we’re concerned,” said Jonathan Olson, Pike’s regional manager.

That argument isn’t persuasive to Warren Knight, whose family owns nearby Smiling Hill Farm. In his view, the rock isn’t so special. The bedrock formation that Pike wants to mine exists in many places across southern Maine, Knight said, and any rock quarry that does business with the state must meet the minimum quality standards.

It’s true, Knight said, that the quarry’s location is desirable for Pike, but it’s just too close to businesses and homes. “If you could extract rock in downtown Portland, you’d have a competitive advantage,” he said.

An Idexx spokesman said the company isn’t qualified to comment on the qualities of the rock. But if the quarry is so valuable, said Dick Daigle, director of facilities for the biotech company, the city should tax the property to reflect that value. The quarry is taxed at a lower rate than adjacent commercial property, he noted.

Geology and zoning have put Idexx and Pike on a collision course. Idexx says it will create 500 jobs with a $50 million expansion of its headquarters, a half-mile from the quarry, but only if the industrial park where both companies operate is rezoned to limit Pike’s ability to blast and crush rock. Pike says such restrictions would put it out of business at the site.

While Pike fights the zoning change, it also awaits a court ruling on its appeal of a shutdown order by the city. The Zoning Board of Appeals ruled in July that Pike doesn’t have the right to operate the quarry because its predecessor there, Blue Rock Industries, never met conditions the board set for the site in 1968.

City and state leaders are now trying to fashion a compromise; a public hearing is set for next week. But what can’t be negotiated is the geology.

The rock that formed here began as marine sandstone, laid down between the Ordovician and Silurian periods, when North America straddled the equator.

“These rocks have a complicated history,” said Henry Berry, a bedrock geologist for the Maine Geological Survey. “These sediments were deposited in an ancient ocean that no longer exists.”

Several million years later, heat and pressure baked the rock, creating dense material with microscopic mineral deposits, largely quartz, feldspar and mica. “That metamorphism is what makes these rocks very hard,” Berry said.

Geologists have mapped the rock deposits. One band, running through southwest Maine, is known as the Berwick Formation.

Blue Rock Industries recognized the commercial potential of the deposit. It began mining a 20-acre section of the deposit a few miles away, on Main Street in Westbrook. Today, the area is surrounded by shopping centers and offices, skirting a 320-foot-deep pit from which 18 million tons of rock have been excavated over the past 67 years.

Now, that quarry is depleted. That’s why Pike has so much riding on Spring Street, where 40 years of excavation has only skimmed the top of the 32-acre site.

Contractors need aggregate — crushed rock — to make concrete and asphalt. The best aggregate is very dense and won’t easily absorb water. It’s also very strong, to stand up to heavy traffic. And it has sharp edges, so asphalt sticks to it.

Highway engineers have developed standards to measure those characteristics. Recently, they have begun relying on the Micro-Deval test for asphalt.

Into a steel cylinder go stone samples, water and steel balls. The mix is spun for two hours at a certain speed, then drained through a sieve. If more than 18 percent of the material breaks down and is lost through the holes, the rock isn’t used for making asphalt on Maine highways, said Rick Bradbury, a quality assurance engineer for the Department of Transportation.

How does rock from the Spring Street quarry measure up?

Tests show it has a Micro-Deval rating of 6 percent to 9 percent.

“That’s a very good stone,” Bradbury said. “A 6-to-9 Micro-Deval is a very hard stone.”

This week, Bradbury compiled a two-year review of the Micro-Deval ratings from asphalt plants in southern Maine. The average was under 11 percent. The state doesn’t test specific quarries, Bradbury said, because contractors often blend stone from more than one quarry, or wash the rock to remove loose particles, to meet the standard.

Pike also operates rock quarries in Wells and Poland. In Wells, the rock’s Micro-Deval rating is 8 percent to 10 percent. In Poland, it’s 8 percent to 16 percent, according to Pike.

Spring Street also scores well on an older, complementary testing method — the Los Angeles Abrasion test — for making concrete.

Such characteristics would have little economic value if the deposit were under a thick mantle of dirt and clay. It would be too expensive to dig out. But the Spring Street rock has a thin overburden. In some places, the bedrock is exposed.

And, as with all real estate, location is critical. The quarry would be worth less if it were in Aroostook County.

Spring Street is a five-minute drive from the turnpike. It costs $1 per minute to run a 24-ton dump truck, Olson said.

With Spring Street idle at least temporarily, Pike is trucking rock from Wells and Poland. That adds to its cost of working in Greater Portland.

And, he said, “One dollar a ton could be the difference between being a low bidder and not getting work.”

Staff Writer Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story