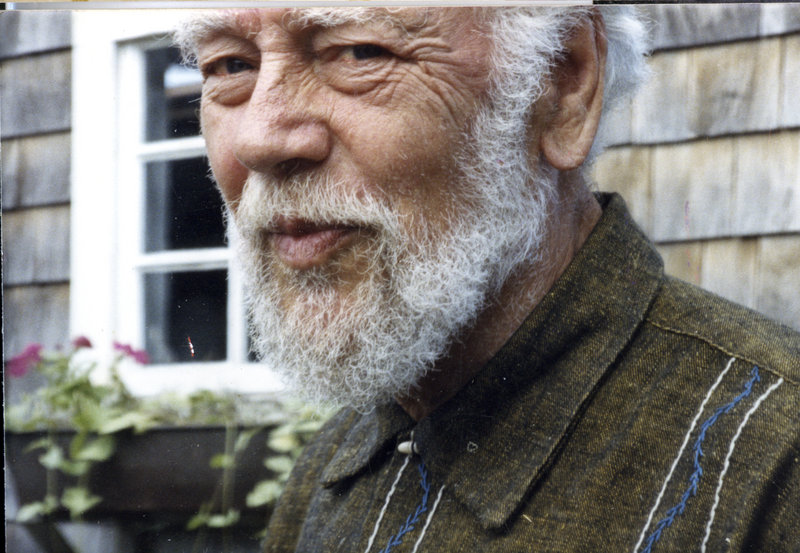

MONHEGAN — Charles Martin was born in poverty, and by age 14 had taken a factory job to help support his family.

He was a tough son-of-a-gun, skilled as a boxer and amenable to manual labor. He did what he had to do to get by, and that sometimes meant surviving on the skills and guile of an artist.

As a teenager, Martin drew posters for local movie theaters in and around Boston for extra cash. Later, he followed the summer crowds, and hawked his drawings and portraits to tourists when they disembarked at the docks of Provincetown and other touristy destinations from Boston to New York.

Even after Martin carved out a distinguished career as an illustrator for The New Yorker magazine, he never wrapped his head around the idea that he had become a successful artist.

“It was difficult for him to think of himself as an artist,” said his son Jared Martin, seated in the living room of a simple house on Monhegan Island that Charles and his wife, Florence, purchased in 1960. “That ‘artist’ question bedeviled him his whole life.

“He wanted to be a real artist, a fine artist. But unlike some of the other fine artists who went to art school and thought of themselves as an artist, Charlie thought of himself the other way. ‘I’m a street artist, and a boxer.’ He never saw himself as an artist. Never.”

Martin retired to Maine, and spent half the year on Monhegan. In the late 1980s, he and Florence bought a place in Portland and gave up their life in New York. In 1995, he died at age 85 in a Portland retirement home. His widow died in 2009.

Martin’s ashes are buried on Monhegan, in a cemetery that lies on a sloping hill below the Monhegan Museum.

Before he died, and certainly in the years since, the rest of the world caught up with Martin. Even if he never saw himself as an artist, his legacy is firmly established. The Portland Museum of Art featured his work in 1990, and an obituary in The New York Times noted his success as an artist and illustrator.

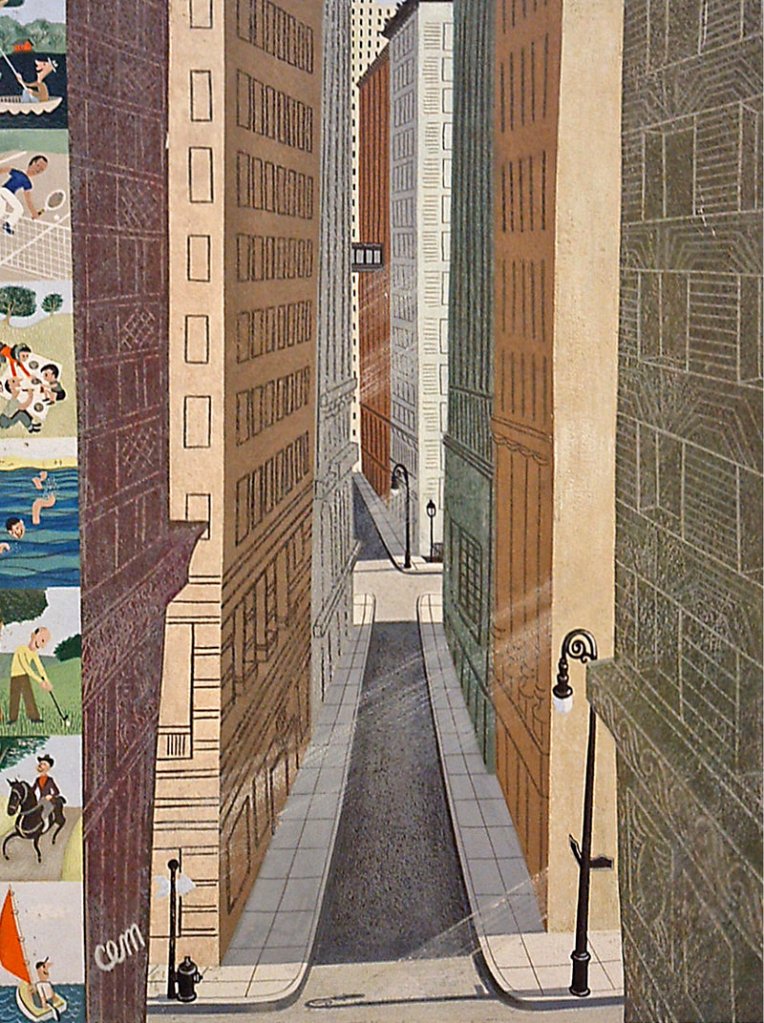

This month, Greenhut Galleries in Portland shows several of the original illustrations that Martin did for The New Yorker. In all, he illustrated 187 covers for the publication, and contributed many more illustrations for use inside the magazine, as well as cartoons. He was known for the initials that he used to sign his work: C.E.M.

Many of his covers for The New Yorker include Maine scenes, including those from Monhegan.

“This is a view that Charlie did 8,000 times,” his son said, standing on the front porch of the yellow clapboard house, which on this day is trimmed by brilliant blue lupines and lilies preparing to bloom. The view is of the island meadow, looking out past the main dirt road that leads from the dock. The top of Manana Island on the backside of the harbor is visible from the porch.

‘LET’S GO THERE’

Martin ended up on Monhegan by chance. “He saw a sign that said, ‘Boat to an island,’ and he said, ‘Let’s go there,’ ” his son said.

He got off the boat and ran into an artist friend from New York. They had worked together as Works Progress Administration artists in the 1930s.

Martin felt immediately comfortable on the island. He knew a few people, met many more and made quick friends, and fell easily into the island life. He came for the first time in 1954, and purchased the house in 1960. Thereafter, Martin and his wife spent most of May to October on the island.

Jared Martin remembers coming here as a kid, and how happy his parents were to be here. They never locked their doors, and it seemed they hadn’t a care in the world when they were on the island.

“He got to hang out and rub shoulders with real fishermen,” Jared said. “He liked that a lot. He would say, ‘These guys are tough. And the women are tougher.’ “

In the very early years, Martin came to Monhegan to get away. He told his editors back in New York that they might not hear from him for a few months.

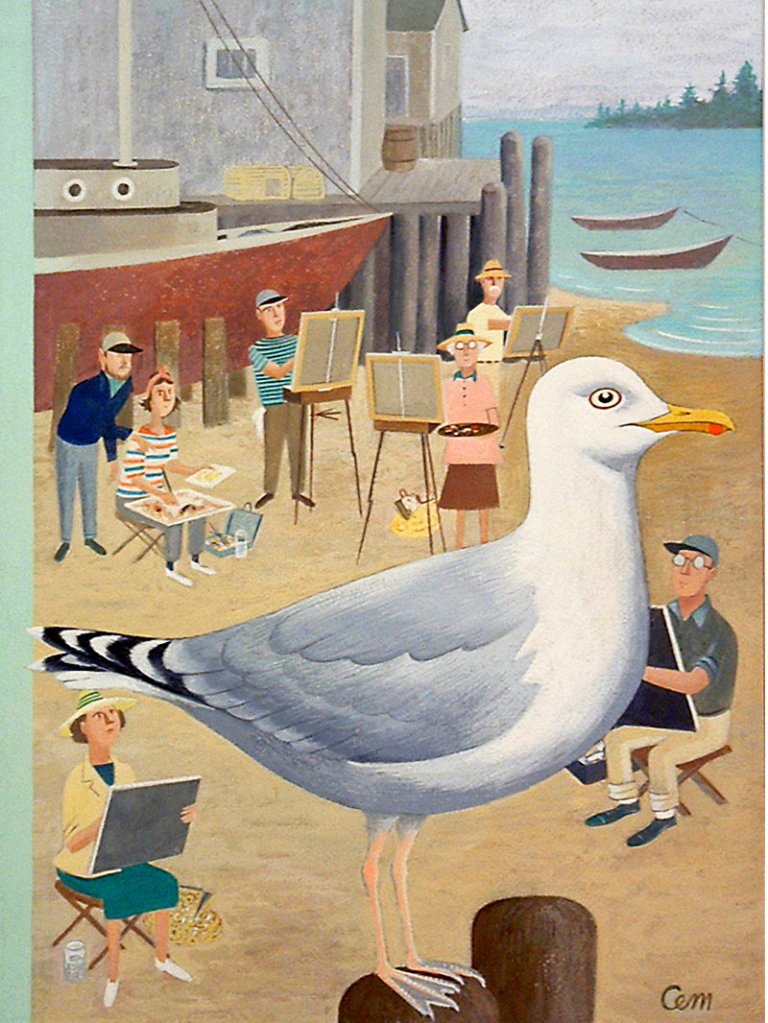

Later, as the family fell into a routine that centered around their island house, Martin began sending illustrations back to New York that included Maine scenes. One of the most famous, from August 1960, humorously shows a seagull perched on a piling with a group of easel-bound artists eagerly painting away. With that piece, Martin captured the crazy Sunday-painters scene that has evolved on the island.

Monhegan changed his father’s art, Jared said. “He came up here and his stuff was lighter, more pastel-ey. It seemed to open him up.”

During his time in Maine, he also illustrated several children’s books, and wrote one himself called “Island Winter” in 1984.

In addition to The New Yorker, Martin’s illustrations appeared in Harper’s, The Saturday Evening Post, The Saturday Review, Punch and Esquire. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Library of Congress are among the institutions that include his work in their permanent collections.

Greenhut is showing about 15 covers, said gallery owner Peg Golden. During a recent island visit, Golden also packed up a number of items from Martin’s studio out back, including brushes, a palette of dried ink, an original cover and a few other items. She is displaying those items along with the original artwork.

A video about Martin’s life, made by his son, is also showing in the gallery. (Jared Martin enjoyed a long career in Hollywood, appearing on the TV show “Dallas” throughout its run, and later working as a director.)

Golden called the opportunity to show Martin’s work “too good to pass up. As a New Yorker myself, I think his covers have always resonated with me. Until I met Jared, I didn’t know anything about his life. I didn’t know that he lived in Portland. The more I learned, the more attracted I was to his personality.”

She calls Martin’s style of painting “inviting, colorful and nostalgic. You sort of want to become part of them.”

FIRST COVER IN 1938

The covers themselves were stand-alone pieces of art. They didn’t necessarily refer to content within the magazine, so Martin had total freedom to create. He did his first cover for The New Yorker in 1938, then hit a drought. His next came in 1947, and then a flurry of them through 1985.

During World War II, Martin worked with the Office of War Information as the head of a mobile leaflet unit in North Africa, Italy and France. He edited and illustrated pamphlets and newspapers that were air-dropped behind enemy lines. He also stuffed leaflets into artillery shells, which later were fired at the enemy. If a German came back waving a leaflet, U.S. troops were instructed not to fire.

Jared Martin looks back at his father’s life with a sense of wonder. He lived in very different times than today, and experienced things that most of us can’t imagine, he said.

For a man who spent most of his years chasing the elusive life of an artist, it’s fitting that he came closest to realizing his desired life in Maine, and specifically on Monhegan. On this island, where the likes of Rockwell Kent, James Fitzgerald and countless others found their creative voices, so too did Martin.

He came up here to get away from the madness of New York, and here he found his stride. It’s not coincidental that Martin’s most successful run with The New Yorker came during the years that he spent most of his time on the island, his son noted. Monhegan has a way of rubbing off on artists.

“He came up here and produced like gangbusters,” Jared said.

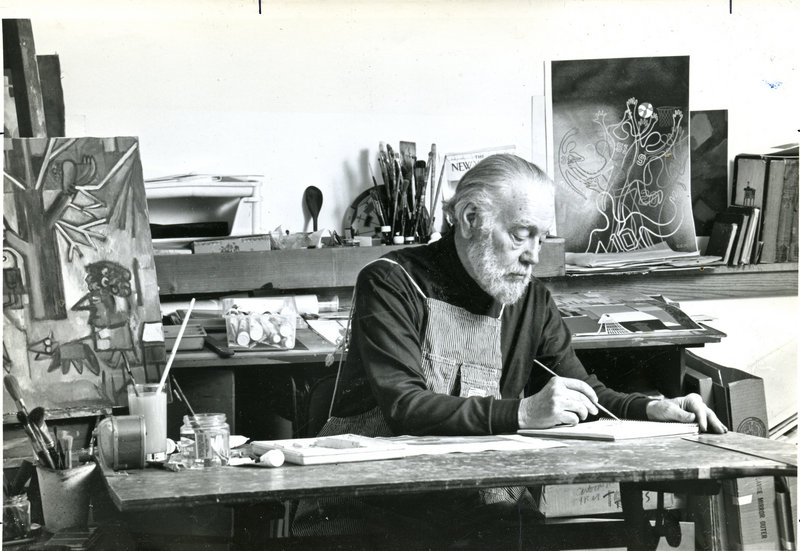

Martin’s studio is still largely untouched since his death, and reminders of his life and his work are prevalent. His brushes stand in a jar, his easel off in a corner. A dusty old suitcase with a tag marked “Martin” sits over on the side. Nautical charts that he liked for their design are tacked to a wall.

All are remnants of the life of an artist, well lived.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Follow him on Twitter at:

twitter.com/pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story