The death of a 45-ton right whale found entangled in fishing line about 12 miles off the Maine coast over the weekend has caught the attention of the Maine lobster industry even though it’s not clear whether the whale’s demise was related to lobster fishing. The right whale is endangered and protected by the federal government.

Patrice McCarron, executive director of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, said preliminary indications appear to show that the ropes found on the whale were much larger than those typically used by lobstermen. The larger ropes would instead more often be found in deep-sea fishing, she said.

Jennifer Goebel, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration spokeswoman, said many aspects of the adult female whale’s death are still being investigated, including tracing the fishing gear to an owner, if possible.

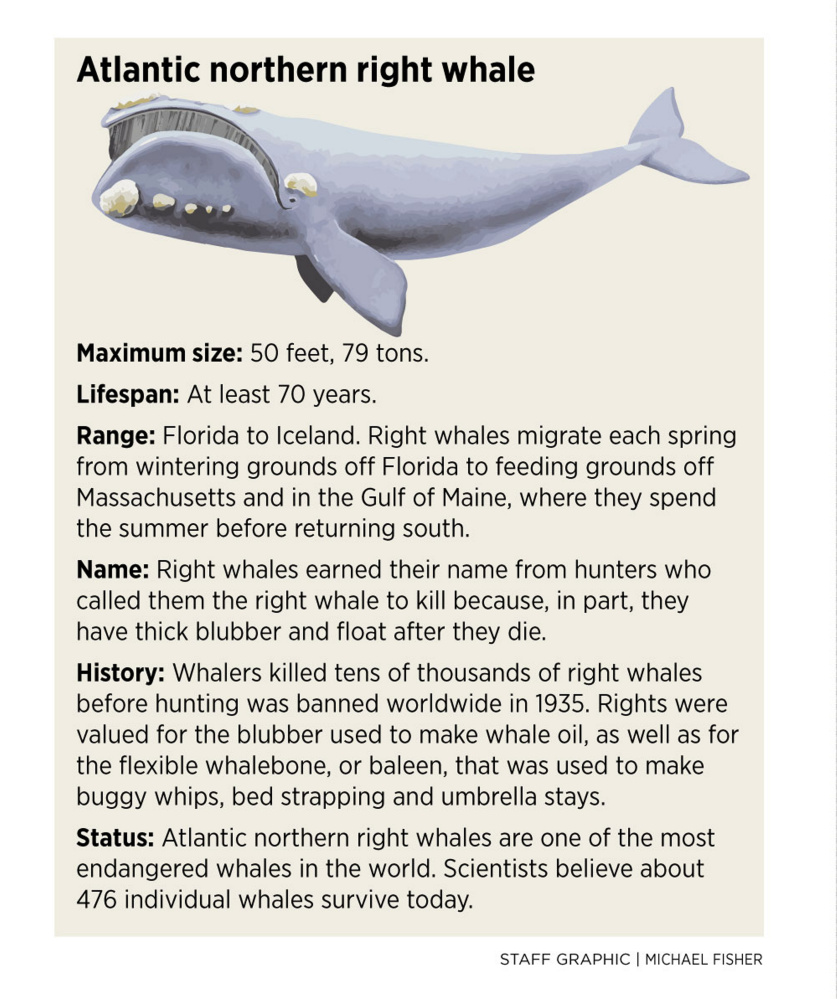

Right whales have been listed as an endangered species since 1970, and one of the greatest threats to their survival is fishing gear entanglement.

Goebel said that even though the whale was found in Maine, it could have become entangled anywhere in its habitat in the Atlantic Ocean up and down the U.S. and Canadian coasts before dying off the Maine coast. A necropsy was performed Sunday at a Gorham farm, which will compost the carcass.

“There’s obviously a lot of things that we are still investigating,” Goebel said.

Much of the lobster harvest occurs outside the right whale’s habitat, McCarron said.

About 80 percent of lobstermen stay within 3 miles of the Maine coastline, because that’s where the lobsters migrate to in prime lobster season, roughly from July through November, she said.

Right whales usually don’t get that close to the shoreline, McCarron said, which is why 70 percent of lobster harvesting waters within 3 miles of the coast are exempt from 2009 federal fishing regulations aimed at protecting the whales.

The right whale population has rebounded since the 1990s, from less than 300 to the most recent estimate of 476 in 2014, according to NOAA.

Amy Knowlton, a research scientist with the New England Aquarium, said in an email that right whales had “some good calving years in the early 2000s” that led to population increases after “lackluster” calving in the 1990s that may have been caused by disease or food scarcity.

Knowlton said, however, that danger signs such as fewer births and more frequent entanglements have emerged in recent years and could cause the population to plummet again.

“Changes to the (fishing) industry haven’t yet fixed the problem,” she said.

The federal regulations enacted in 2009 require lobstermen to use ground lines that sink to the ocean floor and thus stay out of the way of the whales, instead of floating ground lines that stay on top of the water and can entangle whales.

Lobstermen who want to fish in non-exempt zones have to spend between $7,000 and $10,000 for the sinking ground lines, which have to be replaced every year or two. Floating lines could last about a decade before needing to be replaced, McCarron said.

“It’s a very significant investment,” she said.

Aside from an unknown number of lobstermen who fish in the 30 percent of waters within 3 miles of the coastline that are subject to the federal regulations, McCarron said 1,200 to 1,400 of the more than 7,000 licensed lobstermen have licenses that allow them to go farther than 3 miles offshore to fish for lobsters. However, it’s unclear how many of them actually use the licenses allowing them to fish that far out.

From 2009 to 2013, there were an average of 3.4 right whale entanglements per year in the Atlantic, according to an NOAA study.

“It’s hard to say whether the regulations put in place have made a difference or not,” said Lynda Doughty, executive director of Marine Mammals of Maine, who helped coordinate Sunday’s necropsy.

McCarron said there is little information about how or why the right whales become entangled.

“We really don’t know,” McCarron said. “If fixes need to be made, we want to make the right changes that will truly make a difference.”

McCarron also said that Canadian lobstermen don’t have to follow the same rules protecting whales as U.S. lobstermen.

The Maine Marine Patrol and Coast Guard took turns towing the 45-ton, 43-foot whale to Portland, needing 12 hours to make the trip from where the whale was found Friday off Boothbay Harbor, Doughty said. She estimated that the whale had been dead less than a week when the whale watchers spotted it.

She said the whale was much larger than expected, and it took several attempts before finding a flatbed truck capable of transporting the whale to Benson Farm in Gorham, where the necropsy took place.

A team of 20 scientists from various organizations that conduct whale research worked all day Sunday to take tissue and organ samples to be sent to a pathology lab.

Ed Benson, owner of Benson Farm, which is licensed to accept marine mammals for necropsies and for composting, said the remains of the whale are now being composted and will eventually be sold in Benson Farm’s Surf and Turf soil amendment.

“Composting a whale is the same process that we use for everything else, only bigger,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story