GEORGETOWN — Like many Maine fishermen, Bryan Kelley faces a dilemma as he looks to diversify beyond the lobster that account for the bulk of his catch.

To target pollock, which are relatively common in the Gulf of Maine, he has to fish in the same areas frequented by cod, a type of groundfish protected through strict federal catch limits.

“We literally have to stay away from the codfish,” Kelley said while standing on his 40-foot boat moored in the Five Islands harbor of Georgetown. “I could fill this with codfish if I wanted to, but that wouldn’t help anybody in this sector and that is not why we are out here.”

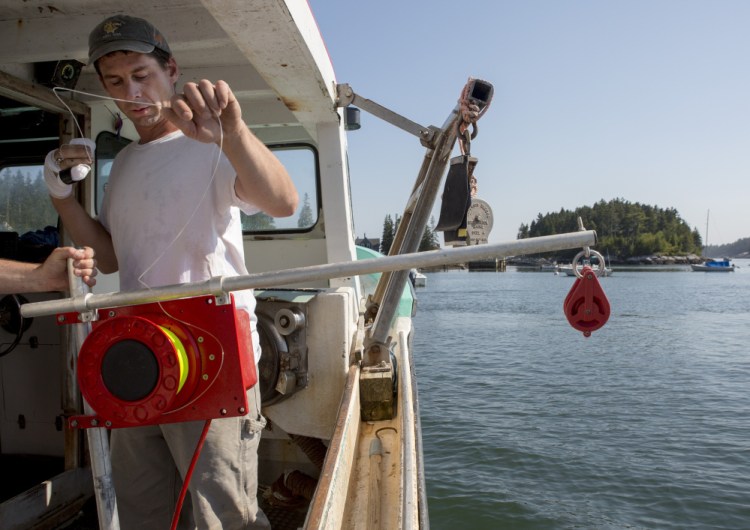

To help him catch the groundfish he wants and avoid the species he doesn’t, Kelley has begun experimenting with a contraption akin to a conventional fishing reel on steroids and with an electronic brain. The “automatic jigging machines” loaned to Kelley and a handful of other fishermen by The Nature Conservancy allow them to more accurately target the water column where pollock hang out and stay off the bottom where cod lurk. The machines’ simple hooks and lures also ostensibly reduce inadvertent “by-catch” of cod while avoiding other downsides of trawlnets and gill nets more commonly used by fishermen.

“That’s part of the draw of it: It’s the quickest and easiest I have ever rigged anything up in my life,” Kelley said.

Geoff Smith, marine program director at the Maine chapter of the The Nature Conservancy, said preliminary reviews of the machines have been largely positive.

“This project is really about helping fishermen target those healthy stocks (of fish) while avoiding the codfish to allow them to rebuild,” said Smith, whose organization owns several groundfish permits in the Gulf of Maine. “We really feel that these jigging machines, if fished properly, can be selective and have minimal impact on the seafloor. … And if they work for fishermen, we think they could be a real game-changer.”

BENEFITS OF JIGGING MACHINES

The jigging machine project is an example of the types of collaboration among fishermen and organizations that might have been unheard of decades ago. Working with the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, the project aims to re-engage small-boat fishermen in an industry that was once the backbone of New England’s coastal economy, but now numbers just a few dozen boats in Maine.

“With these jigging machines, we have seen a lot more interest from lobstermen in getting involved in groundfishing than we have had in a long time,” said Ben Martens, executive director of the fishermen’s association, a nonprofit founded by Port Clyde-based fishermen a decade ago.

Automatic jigging machines have been used elsewhere – most notably in Iceland and the Pacific Northwest – but are fairly uncommon in the Gulf of Maine, where trawls or gill nets were typically used to catch groundfish.

The machines, which are about the size of a small outrigger engine, attach to the side of the boat and feature a spool of heavy fishing line outfitted with six to 10 hooks. The machine drops the weighted line to the seafloor and then raises the hooks back up to the level specified by the fisherman. The “jigging” part of the names comes from the machine moving the hooks up and down in the water column to draw the attention of the fish.

Finally, sensors detect when a certain amount of tension or weight is on the hooks, triggering the machine to automatically retrieve the line. Fishermen then hand-remove the fish from the line.

Kelley said that during a recent trip, his crew hauled in roughly 2,300 pounds of pollock in a four-hour period. He uses simple, hard plastic lures, eliminating bait costs and allowing him to potentially bring on another deckhand. And with fresh pollock fetching anywhere from $2 to $3.50 a pound – compared to the 80 cents a pound Kelley said he used to receive for groundfish – the Georgetown lobsterman is already planning to purchase his jigging machines from The Nature Conservancy and invest in a few more.

“It gives us another season. There’s no downtime,” said Kelley, who, like many Maine lobstermen, has fished for everything – scallops, shrimp and other species – when the lobster are out-of-season or the fishing isn’t good.

In 1989, Maine fishermen landed more than 12 million pounds of cod alone, only to see the fishery peak and then collapse several years later. This year’s cod quota – or “annual catch limit” – for the entire Gulf of Maine is just over 600,000 pounds.

Groundfish accounted for just 2 percent of total poundage – and just 1 percent of the total value – of seafood landed by Maine fishermen in 2015, according to the Maine Department of Marine Resources. Lobster, by comparison, accounted for 44 percent of the total poundage and 81 percent of the monetary value of seafood landed in the state last year.

BUYING PERMITS TO AID RESEARCH

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has designated Gulf of Maine cod as “overfished” and well below the “target biomass level” needed to rebuild the stocks. Pollock, by comparison, are not considered overfished in the gulf in 2016 and have a federal quota of more than 30 million pounds. But after years of ever-tightening quotas, the number of Maine fishermen holding groundfishing permits has dwindled from hundreds of vessels in the 1990s to just 39 that landed any groundfish last year.

The Nature Conservancy and the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association are among several nonprofit organizations that have purchased groundfishing permits from willing sellers in Maine and other New England states in recent years as part of the groups’ focus on sustainable fishing. The organizations then typically lease the quotas, or “catch shares,” associated with those permits to fishermen at favorable rates or contracts with the fishermen to conduct research on gear configurations or practices meant to make a fishery more sustainable.

Smith said The Nature Conservancy purchased about 20 of the automated or electronic jigging machines and has installed several on boats in Maine. Participating fishermen are allocated some of the organization’s quotas for pollock as well as for cod to cover any by-catch. The conservancy will sell the machines to fishermen at a discounted rate, if they elect to continue using the technology.

BETTER SUSTAINABILITY PRACTICE

Automated or electronic jigging machines are billed by manufacturers and supporters as being more sustainable because they can be used to more accurately target the desired species. And because fish are quickly retrieved after the line hits a weight limit, any fish that are undersized or of the wrong species can often be released alive or at least in better shape than those caught in a gill net or trawl. Additionally, Smith said the jigging machines do not damage the ocean bottom.

Kelley said the fish he’s been hauling up have been very “clean” – fishermen-speak for “not banged up” – which often can help them command a higher price in a marketplace already seeing growing demand for fresh, locally caught fish.

Others see a specialized market for hook-caught pollock.

“We are starting to have conversations with people in Portland and Boston and New York to see if there is a market for that product,” said Martens, of the fishermen’s association.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story