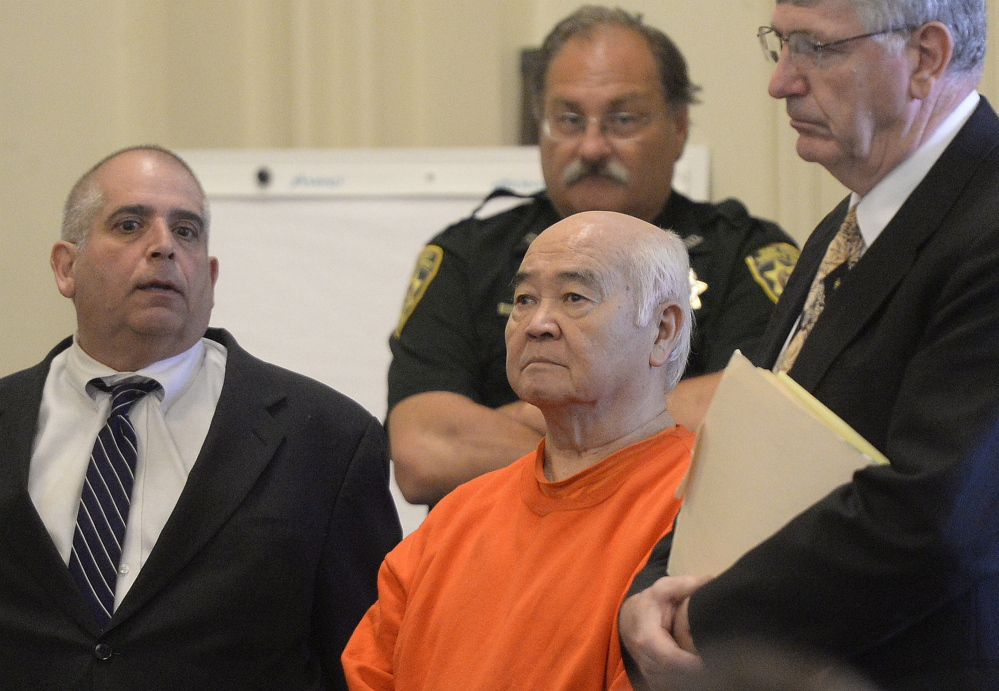

ALFRED — A 75-year-old Biddeford man who is charged with killing two teenagers in an apartment at his home in December 2012 entered a new plea of not guilty by reason of insanity on Tuesday.

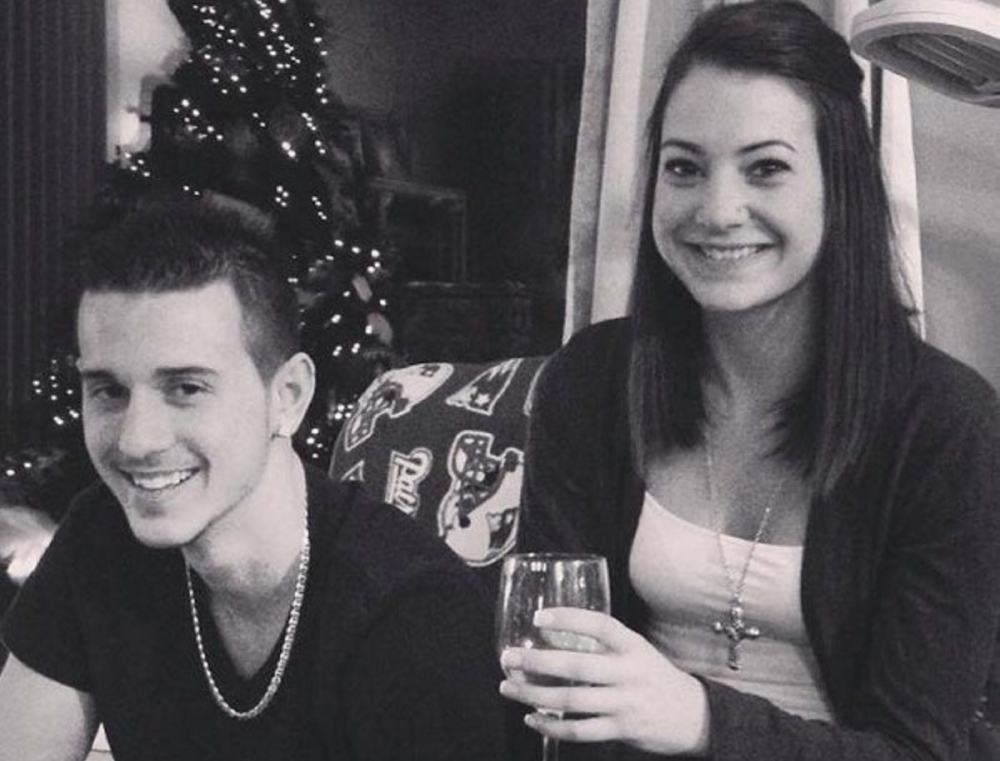

James Pak had initially pleaded not guilty in March 2013 to two counts of murder in the deaths of Derrick Thompson, 19, and Alivia Welch, 18. Authorities say he fatally shot Thompson and Welch in the apartment that he rented to Thompson and his mother, Susan Johnson, 45, after a dispute over parking.

While the new plea doesn’t change the status of the case against Pak, who remains in custody at the York County Jail, it is a rare move in a criminal defense and is invoked almost exclusively in the most serious of felony cases.

Even if Pak is found not criminally responsible for the shooting deaths on Dec. 29, 2012, he would likely spend the rest of his life in the custody of the state, either at Riverview Psychiatric Center in Augusta or another supervised setting.

Nearly 20 percent of the 88 people in Maine who are currently in the custody of the Maine Department of Health and Human Services after being found not criminally responsible had initially been charged with murder.

In the past 20 years, only three people found not criminally responsible for murder have been discharged from state custody. Most of them die in state custody, according to Department of Health and Human Services data.

At Tuesday’s hearing in York County Superior Court, Pak stood silently in an orange jail uniform while Johnson, members of her family and members of Welch’s extended family watched from the spectator section of the courtroom.

Both Johnson and her family and Welch’s family left the courthouse without speaking to reporters.

Pak’s attorney Joel Vincent entered the new pleas on Pak’s behalf on the two murder charges and three other charges in connection with the shootings at 17 Sokokis Road in Biddeford. He is accused of aggravated attempted murder and elevated aggravated assault for allegedly shooting Johnson, and burglary for breaking into the apartment.

After police left

Pak is accused of shooting Thompson, Welch and Johnson just minutes after Biddeford police had left the apartment. Police had been called to investigate a dispute between Pak and Thompson, but left after determining that the argument didn’t warrant police action.

Court documents say Pak waited for police to leave, got a gun, opened the door to the apartment and said: “I am going to shoot you. I am going to shoot you all.”

He shot Johnson first, then Thompson, then Welch, court documents say.

Johnson suffered gunshot wounds to the back and arm but survived. She called 911 after the shootings, but the two teenagers were dead by the time emergency responders arrived.

Superior Court Justice John O’Neil said the next step in the case will be to schedule a hearing on two motions by Vincent and Pak’s other attorney, Lawrence Goodglass, sometime in late August.

In their motions, Pak’s attorneys plan to challenge a finding by psychologists for the State Forensic Service regarding his mental competency and to have statements he made to police on the night of his arrest deemed inadmissible.

Details of what doctors found when they examined Pak during his stay at Riverview last year have been sealed.

Pak’s attorneys and the prosecutor, Assistant Attorney General Leane Zainea, declined to say what psychologists found in their examinations of Pak since his arrest.

“He’s gone through a battery of tests. I expect he will be examined more by our experts,” Vincent said. “It’s been a long time, but there has been a lot going on behind the scenes.”

Vincent said he disagrees with the idea that entering a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity is a long-shot defense.

“I’ve had clients in homicide cases be found not guilty by reason of insanity before. It certainly isn’t a Hail Mary plea,” Vincent said.

A risk for the defendant

Data on the success rate in Maine of pleading not guilty by reason of insanity were not immediately available.

Christopher Northrop, a clinical professor at the University of Maine School of Law who begins a term this week as president of the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said the so-called insanity plea often poses a risk for most criminal defendants.

“In many cases, you get a much more severe sanction if you are found not guilty by reason of insanity than if you were sentenced to a particular time,” Northrop said.

Someone who is convicted and sentenced to prison can calculate his release date, factoring in early release for good behavior. But a person found not criminally responsible remains in the custody of DHHS for an undetermined amount of time that could exceed the penalty of many lesser crimes, Northrop said.

“So when you do see it, you almost only see it in very serious instances and when you are more likely to spend the rest of your life incarcerated,” he said.

Nearly every person who is in state custody after being found not criminally responsible had initially faced a felony charge – mostly arsons, assaults, attempted murders and murders. Only four of the 88 in custody had originally faced misdemeanor charges, such as carrying a concealed weapon and stalking.

Sixteen people who were found not criminally responsible for murder are now in state custody. The oldest of those homicide cases dates back to 1970. The most recent was from 2010.

Ann LeBlanc, a state psychologist and director of the State Forensic Service, said that in order to be found not criminally responsible, defendants invoking the insanity defense have to demonstrate a “seriously abnormal condition that grossly and deeply impairs their ability to comprehend reality.”

LeBlanc said they must first be found competent to stand trial. Someone with dementia, for example, would likely not be found competent.

Once committed as new patients to Riverview, defendants would undergo about six months of mental and medical evaluations before hospital staff would consider giving them restricted freedom, such as going to the gym or being allowed to eat meals in the cafeteria rather than their unit.

“For patients being found not criminally responsible, the burden is now on them to demonstrate to the court that they are safe,” LeBlanc said.

‘the only test’

To gain any level of release, such as being allowed out of the state hospital with one-on-one supervision for a couple of hours, the patient must petition the court. The hospital would conduct an assessment, and the State Forensic Service would evaluate the petition for a judge to consider, she said.

“There is no blood test that says they are now safe. There is no MRI to say a patient is now safe. I am fond of saying the only test is the test of time,” LeBlanc said.

Although patients can file petitions for release every six months, they could gradually be allowed out to do things like go to church unaccompanied or volunteer in a soup kitchen, LeBlanc said.

If they do well, they can petition to live outside the hospital, first in a group home with constant supervision, then in a supervised apartment building and possibly even an independent apartment with regular psychological and psychiatric appointments, she said.

“It’s extremely gradual. Petitions are required at every step,” LeBlanc said. “It would be very rare for someone to go directly from the hospital to an independent apartment.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story